It was not an ideal spot for a phone call but there I was, balancing between cars on a train traveling back home to Berlin, talking with Joshua Salzberg, who was calling from Budapest, where he was working on a film.

Salzberg knows I am a religion nerd. The film he adapted with co-writer/director Shira Piven — “The Performance”— featured a cast of characters with varying religious identifications. The team wanted to get the details right. Down to the minutest items.

So, there I was, rocking back and forth as the German state of Brandenburg flitted by, talking to Salzberg about the ring a club owner in 1930s Berlin might foreseeably be wearing.

That attention to detail impressed me. The care and concern that Piven, Salzberg and the entire team brought to the film is a testament to its overarching message of resisting hate and finding people’s humanity in the unlikeliest of places.

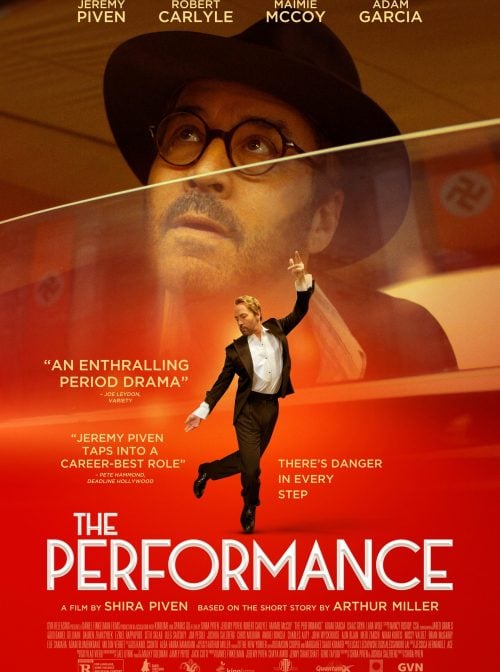

“The Performance,” starring the director’s brother, Jeremy Piven of Emmy-nominated “Entourage” acclaim, is adapted from an Arthur Miller short story of the same name. The story has been described as, “a strange midnight train ride” by Seattle Times critic Richard Wallace, and tells the tale of Harold May, a down-on-his-luck New York tap dancer who heads to Europe in the 1930s in search of new opportunities.

While dancing on the tabletops of a Hungarian night club, May and his troupe attract the attention of Damian Fugler (Robert Carlyle), who invites them to give a special performance at a Berlin nightclub, hefty paycheck included. May, who is Jewish but can “pass” as a blond-haired Aryan, and his fellow performers — including Adam Garcia as the politically attuned Benny Worth, Isaac Gryn as a closeted Paul Garner, Lara Wolf as the namesake of a Persian princess “Sira” and Maimie McCoy as a recently divorced, single dancer Carol Conway — are fast-tracked through a series of ethical, moral and professional through stations as they tap their way into a performance none of them really want: a private show for Adolph Hitler.

The story chugs along like “a modern, gothic folktale,” with the personal stakes becoming ever greater until it all falls off the rails, when their experience of opulent luxury at the behest of their German hosts contrasts too starkly with the increasingly evident persecution of Jews, homosexuals and other so-called “undesirables” around them.

The potent parable first came to the Pivens’ attention thanks to their mother, distinguished acting teacher Joyce Piven (who died at age 94 in January). Shira thanked her mother and father, Bryne, who founded the Piven Theatre Workshop in Chicago more than 50 years ago, for always being on the lookout for a good story. “They had this idea of taking folk tales and fairy tales and making a play out of them,” she said. “My mom was always looking for pieces that could be adapted. And she found this short story by Arthur Miller called ‘The Performance,’ and thought it would make a great film.”

From Joyce Piven’s introduction to the filming of the final scene and beyond, Shira said the production brought the family closer together and resonated with her upbringing in a Reconstructionist Jewish family where theatre was often “their religion.”

“As I worked on the film, I thought it was about May getting in touch with his Jewishness that made him recognize his commitment to the greater whole,” Piven said, “but then I realized it was almost the reverse — that it was getting in touch with this larger sense of humanity that put him in touch with his Jewishness.

“It comes down to the struggle to do good in the world — through your profession, your religion, your craft, your connection to others,” Shira said.

To adapt the short story for the screen, Shira brought in Salzberg, who worked as editor on one of her previous projects, 2014’s “Welcome to Me.” Salzberg, who is half-Jewish on his father’s side, was raised Lutheran but also occasionally celebrated High Holidays and mitzvahs, was taken with the project from the start.

“When Shira brought it to me, I thought of it as this captivating, larger-than-life folktale,” Salzberg said. “There are a lot of stories from that time period, for good reason, but this speaks to so many of us and our desires for success and acceptance, the pressure to assimilate, and our susceptibility to go along with authoritarianism if the right carrot is dangled in front of us.”

Though the story centers on a main character wrestling with his Jewish identity, which he is forced to hide both in the pre-war United States and Nazi-era Europe, Piven and Salzberg insist it is not specific to people of a particular cultural background. “Depending on the flavor of the moment in society,” Salzberg said, “any one of us may feel that pressure to pass as an American or erase your specificity to fit in.”

To Shira’s credit, Salzberg said, there is a rich mosaic of characters, each with their own complexity and nuance. This ranges from the closeted club owner — of Moroccan background in Miller’s story — who leveraged his role as a popular night club owner to keep the powers that be entertained; his love interest in the troupe, Paul, who also struggles with a stutter and hides behind his camera; or Carol, who was going through a divorce and faced social pressures as a single woman on tour.

Behind the camera, Piven and Salzberg also describe a “special little group” who brought their whole selves to the production itself, learning and growing together along the way.

Not only were there seven different languages on set, which presented its own practical challenges, there were also robust conversations about theology and religious ritual. In particular, Piven and Salzberg turned to rabbis who coached the team on the specifics of historical Judaism or practices such as the proper way to kiss the mezuzah — a small piece of parchment with specific Hebrew verses from the Torah, housed in a decorative case and mounted on a doorpost.

“As a Reconstructionist Jew, this wasn’t part of my upbringing,” Piven said, “so at one point we had Orthodox Jews on set discussing the proper order and method.

“The level of detail in the discussion was stunning,” she said.

While filming, the cast and crew also celebrated Hanukkah, the Jewish Festival of Lights, an eight-day commemoration of rededication of the Temple by the Maccabees in 164 BCE. Two local rabbis came to the set to lead celebrations and give a blessing. “The blessing was both specific and universal,” Piven said, “it spoke to those who were religiously Jewish, but it also spoke to all of us.

“Whatever our background, we found a connection. It was all very moving,” she said.

That ability to connect across differences, to be blessed by each other’s presence, and to argue in a constructive way can feel far from where we are right now as a society, Piven said, with so much “black-and-white thinking” about domestic and global politics. But that is the power of Arthur Miller’s message of resistance and resiliency for a new generation, she added.

“Literature, film and art have the ability to help us look at two things that are seemingly antithetical and look beyond the polemic,” Piven said. “I never set out to make that kind of movie, but the characters — and the cast that made them come to life — confront us in a way that we need to be challenged right now: to see other people’s humanity even when it might be hard to.”

That message hit home for Salzberg, who said the process of adapting Miller’s story for the big screen changed his life. Saying Piven embraces the “process of discovery” through hours-long conversations about a scene or a character, Salzberg found himself re-discovering aspects of his own multi-faith upbringing. “In the process of doing this project across religious lines, heritages, perspectives, and identities, it brought into focus who I am,” he said.

Inspired by the experience, Salzberg felt drawn to working with a local, Los Angeles interfaith group, Clergy and Laity United for Economic Justice (CLUE), advocating for local low-wage workers and on behalf of immigrant families across the Southland.

“It’s been my first experience with an intentional, interfaith community,” Salzberg said. “Sometimes there are fears in your head about how to have conversations across difference,” he said, “but I’ve found the opposite through this film and this work — the easiest thing to do is to have a conversation, to be yourself, because everyone is an outsider, coming from a different point of view.”

Ken Chitwood

Ken Chitwood is a religion nerd, writer and scholar of global Islam and American religion based in Germany. His work has appeared in Newsweek, Salon, The Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post, The Houston Chronicle, The Chicago Tribune, Religion News Service, Christianity Today, and numerous other publications. Follow Ken on Twitter @kchitwood.