A Top Veterinary School Tries Something New: A Class in World Religions

April 21, 2022

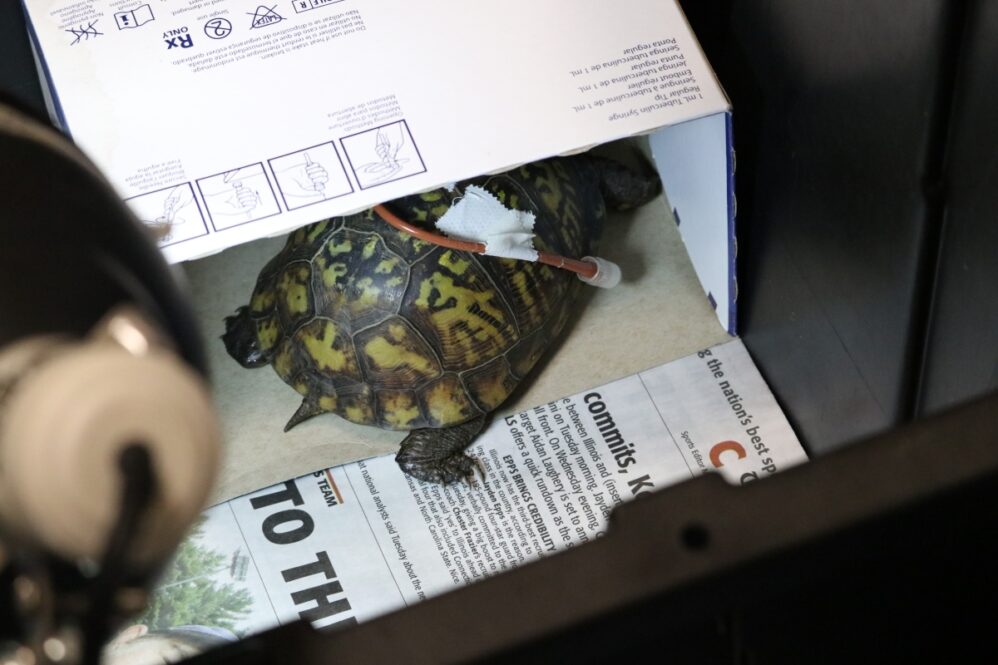

On a busy winter evening at the University of Illinois veterinary school, professors operated on a dog while students watched on a monitor. In the wildlife medical center, a tree frog recovered from surgery while his neighbor, a box turtle with a cold, drew nourishment from a tiny feeding tube taped to his shell. And in the anatomy lab, a fuzzy pile of gray and white bunny cadavers, having done their service to science, were gently loaded into black plastic bags.

All in all, it was a typical evening. But down the hall from the anatomy lab, two professors were conducting an unusual experiment: a world religions class.

Share

Related Articles

Frog recovering in the wildlife center. (Silma Suba/Interfaith America)

Jonathan Ebel, a historian who leads the university’s religion department, and Dr. Yvette Johnson-Walker, a veterinary epidemiologist, led the class. Intrigued by the possibility of creating a course that would blend their two fields, they developed a new syllabus last summer. With some support from the university’s diversity and inclusion office and curriculum guidance from IFYC, Ebel and Dr. Johnson-Walker debuted Veterinary Medicine 694: Religious Perspectives on Caring for Animals. As far as Dr. Johnson-Walker knows, the class is the only one like it at a veterinary school.

“One of the things I really like about this issue is it cuts across whether you’re working with companion animals or food animals or even in public health,” Dr. Johnson-Walker said.

What does religion have to do with veterinary medicine? Quite a lot, it turns out.

Students learned about how different cultures and religions think about death and euthanasia, burial practices, animal ownership, technology and medical intervention, and ethics around slaughtering and eating animals.

Students studied “ethics from a Jain perspective or a Buddhist perspective of euthanizing a pet,” for example, Ebel said. “Surprising to all of us, one of the students brought up the emotional and spiritual (impact) on veterinarians themselves of the routinized euthanasia.” They discussed what veterinarians might do to help each other bear those emotional burdens.

“It’s gone better than we ever imagined. Some of that are these sorts of hidden connections and resonances that you don’t know are there until you start teaching,” Ebel said.

“It definitely opened up my eyes,” said Mariah Miller, a third-year veterinary student who hopes to move to the Chicago area after she graduates and work in a practice that cares for cats, dogs and other small animals. “Every time I go to class, it feels like therapy session. We’re all talking about such deep things, and I kind of love it.”

Student in the Religious Perspectives on Caring for Animals class. (Silma Suba/Interfaith America)

Students looked at a case study about the use of microchips to trace horses in the Amish community, a controversial topic in a religious community with strong concerns about the use and impacts of technology. Students heard from guest speakers of different traditions, gave presentations on the role animals play in different cultures, and learned about the “human, animal, environment triad,” Dr. Johnson-Walker said. “That idea that everything you do impacts all three.”

Dr. Yvette Johnson-Walker of the University of Illinois School of Veterinary Medicine. She co-taught the course with Jonathan Ebel, a religion professor.

In India, for example, the Zoroastrian community relies on vultures and other carrion birds to consume decomposing bodies. The same vultures also consumed decomposing cows, which are considered sacred by India’s Hindus. But when an anti-inflammatory drug for cattle proved to be poisonous to vultures, the bird population began dying off, interrupting the Zoroastrian custom.

“You’d never think that giving pain relief to your elderly cow would somehow impact the burial rituals of some other religion,” Dr. Johnson-Walker said.

Veterinary students assist professors performing a surgery. (Silma Suba/Interfaith America)

Students discussed cultural views of animal ownership: dogs on some Native American reservations are seen as belonging to the land, not as individually-owned pets, for example, something veterinarians have had to navigate when called upon to provide care.

“There was a lot of conversation around ethical decision making. What is harm? And is our responsibility alleviate harm and avoid causing harm?” said Ross Wantland, who as Director of Curriculum Development and Education in the university’s inclusion office, helped coordinate the class. “And human animal and nonhuman animals. Especially as we started out thinking about Hinduism and Jainism and some Eastern traditions, are we the ones who are supposed to be in charge of these animals? Do we own them?”

For Dr. Johnson-Walker, an alumna of University of Illinois, the class was an important step toward making the program more inclusive. She has worked with the American Association of Veterinary Medical Colleges on efforts to diversify the pool of candidates applying to veterinary schools, as well as build cultural awareness in their graduates. Veterinary medicine is the least diverse of all the medical fields, she notes. The Illinois school opened in 1954 with 24 students, all World War II veterans, and all men. In the photos of graduating classes that line the hallways, women have gained ground, but the majority of the faces are white.

Dr. Johnson-Walker notes that the 4-year Illinois graduate program is demanding and expensive – close to $50,000 annually, including room and board, for in-state applicants — and experience with a veterinarian has traditionally been a prerequisite at many schools.

“There is, I think, a fair amount of pressure for some folks that if you’re smart enough to be a veterinarian, you could also be a physician and earn more money,” Dr. Johnson-Walker said. The COVID-19 pandemic may be changing that: applications to Illinois’ program surged 88% this year as demand for veterinarians increased around the country.

“Everybody got a pandemic puppy and now they’re sick or misbehaving,” Dr. Johnson-Walker said. “Practitioners have been sort of slammed.”

Box turtle in wildlife recovery center. (Silma Suba/Interfaith America)

As the student body slowly diversifies, the new religion class “was an effective way to address cultural diversity and inclusion” in the curriculum, Dr. Johnson-Walker said. “Many of our students come from small town, rural backgrounds where they don’t see a lot of diversity growing up, and many of those students end up working in urban settings where there is a lot of diversity.”

At the final class of the semester, 28-year-old Gabi DeOliveira, a third-year student interested in emergency medicine, watched a classmate give a presentation on Inuit and Native American perspectives on animals, followed by a discussion on how they could use this class to build clientele and provide better customer service when they move on to their own veterinary practices.

DeOliveira, who spent part of her childhood in Brazil, said the class changed how she will view her future clients.

“What will stick with me most about this course is I thought that I was pretty open-minded and had a good understanding, coming from Brazil, having lots of different faiths and cultures in my best friends and family,” she said. “But I think I used to avoid a lot of thinking through some of these tough topics.”

The class was small – only four students — but considering it was a pilot program, Ebel and Dr. Johnson-Walker saw it as a win. The students created a bit of a buzz in the halls of the school of veterinary medicine, spreading the word about the new course and becoming evangelists for why veterinarians need religious literacy in their tool kits.

“I’ve had several students reach out and ask when we’re having it again,” Dr. Johnson-Walker said.

Photo gallery by Silma Suba.

This article was originally posted on February 23, 2022.