Ritual and Commencement in Pandemic

April 29, 2020

Colleges can be understood as their own communities where deep bonds are formed, and identities are forged that last a lifetime. On every campus, rituals of some kind welcome new students into that community, and when it is time, send them forth as graduates and alums. Due to the pandemic that has closed colleges across the country, there is a pervading sense of loss among the graduating classes of 2020 as traditional exercises of Baccalaureate and Commencement have been forced to take new forms. However, there has also been a great deal of reflection and creativity in how to make sure there is some virtual observance that will be meaningful for the community.

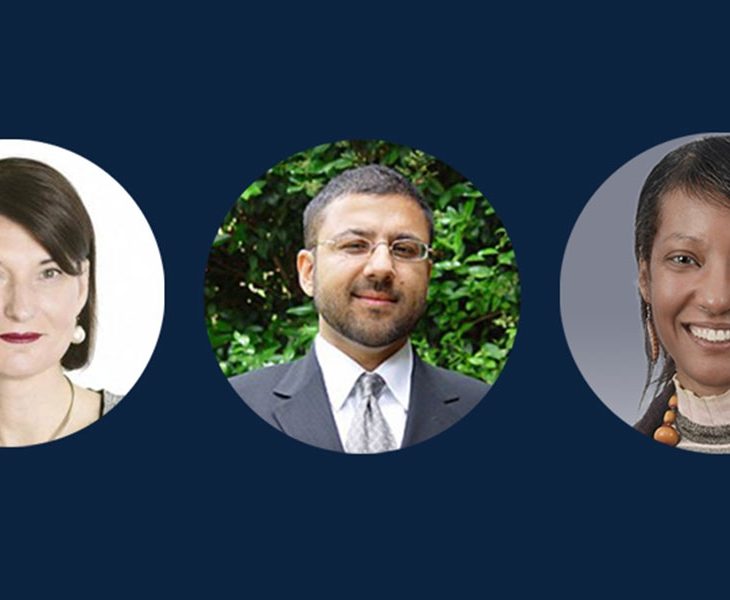

In an April 28 Webinar, Paul Brandeis Raushenbush, IFYC Senior Advisor for Public Affairs and Innovation, was joined by three veterans of spiritual and religious life in higher education, each of whom has been involved in the decisions of how rituals of graduation will be offered in this time of physical distance. In addition to sharing concrete plans for graduations at Howard, USC and Stanford, the three Deans offered important insights into the role of ritual plays on college campuses and what parts of campus life have become understood as essential, and what parts might be ready to fall away. The webinar concluded with a clarion call voiced by all three leaders for universities and society to recognize that the pandemic offers a singular opportunity to move through this crisis to create a more just future for all.

Dr. Varun Soni, Dean of Religious Life, University of Southern California

“When I first started this work at USC, I came to campus thinking my job is to support religious and spiritual communities on my campus. But over time I began to realize that the campus, as a whole, was a spiritual community. We are Trojans, so there was almost a religion of what it meant to be Trojan, whether you were theistic or not, religious or not. It connected all 70,000 people from 145 different countries. It was a shared hope and dream and aspiration. … When we look at the University as a civil religion or a secular religious community, it doesn’t just look like a religion. It often does the work of religion —the meaning making, the work of community building, the work of caregiving, etc.”

Dr. Kanika Magee, Assistant Dean of Student Affairs, School of Business, Howard University

“We really have gathered a number of students for their feedback (about plans for graduation) and what they expressed to us was that the most important part was to hear their name called. Their parents wanted to hear it. Their grandmother and granddad want to hear it. If their name is not getting calls, then what are we doing? … We can drop a lot of other things. The talent can go. The graduation speaker can go. But the opportunity to hear their name called was important. And also, they wanted the opportunity to celebrate each other, that they wanted to hear from each other. We normally have some student speakers. They said the guest speaker does not have to come. But we need to speak to each other. That we are experiencing this together. Only we can understand it. And we want to be able to share that moment.”

Rev. Dr. Tiffany Steinwert, Dean for Religious Life, Stanford University

“We often talk about “being undone” by COVID. Our systems are breaking. It doesn’t work anymore. We worry about higher education or the banking industry. All these things we are thinking of as coming or being undone. I don’t think that’s necessarily bad. Let me say, there are horrible and awful things happening, but the opportunity for us in religious and spiritual life of college campuses is to help our students think critically about how we rebuilt. We don’t and should not rebuild in the image of what was before. We ought to be thinking about what are the creative and new ways we can rebuild, recraft, reimagine, so that the centuries old systemic inequalities – that we design them out of existence, right?”

Share

Related Articles

American Civic Life

The Pandemic Changed Death Rituals and Left Many Longing for Closure

American Civic Life

Natural By Nature, Pagans Expect Some Digital Rituals To Survive The Pandemic

American Civic Life

>> REV. PAUL RAUSHENBUSH: Hello to everyone out there! My name is Paul Raushenbush. I am Senior Advisor for Public Affairs and Innovation at the Interfaith Youth Core.

I am so excited to welcome all of you with us today to have a conversation about what this moment means for graduation, for commencement, for ritual, in higher education and in religion, broadly. I am just honored by all of you joining us. We have been so excited as the list has grown! There’s about a hundred of you on here and we’re hoping for a great conversation. We have an extraordinary panel who are going to help us lead the conversation. But really, this is meant to be a community experience of idea sharing, hope, creativity, and an extension of the love and respect that we have for all of you in the hard work that you’re doing.

I want to just take a moment before I introduce our esteemed panelists to just set a little bit of a table. In my own experience, I was Associate Dean of the Chapel and Religious Life at Princeton University, and I know the role that ritual played in our university life. Both in times of grief, joy, and celebration. But, one of the most important times was in opening exercises and baccalaureate. Our chapel was large enough that the entire entering student body and graduating student body could come into it. They may have never come into Chapel during those other four years, but they were there, and it was a way to show who we were, it was a way to collectively tell the story of Princeton, and to welcome them in and then shepherd them out. One of the things we were interested in is, what do we do in a moment when that no longer becomes an opportunity? So, I am very excited to welcome three esteemed leaders. Their bios are below in your invitation, so you can read more. But I want to at least give a taste of each one of them.

Dean Magee is the Assistant Dean at Howard School of Business. Dr. Kanika Magee is the Assistant Dean of Student Affairs at Howard University School of Business in Washington, D.C. She is the former Associate Dean of the Andrew Rankin Memorial Chapel at Howard University and continues to coordinate campus interfaith education and programming. Welcome, Dean Magee.

I also want to welcome the Dean for Religious Life at Stanford University, Tiffany Steinwert. The Rev. Dr. Tiffany Steinwert is Dean for Religious Life at Stanford University. She previously served as Dean of the Hendricks Chapel at Syracuse University and Dean for Religious and Spiritual Life at Wellesley College.

And, Dean of Religious Life at University of Southern California, Varun Soni, who is currently a University Fellow at the USC Annenberg’s Center on Public Diplomacy and an Adjunct Professor at the USC School of Religion. He is on the advisory board of—and, wait for this list—the Center for Muslim-Jewish Engagement, the Journal for Interreligious Dialogue, the Hindu American Seva Charities, Hindu American Foundation, Future45, and the Parliament of the World’s Religion.

I am extremely pleased to welcome each of these people here today, and each of these leaders and wisdom providers. Thank you so much.

I want to start with you, Dean Steinwert, and talk a little bit about how you understand ritual as functioning at the University? You’ve been to three colleges and universities. Can you introduce the idea of what role ritual can play in higher education and in collective life on campus?

>> REV. DR. TIFFANY STEINWERT: Yeah, I think ritual, at its best, is a practice of shared storytelling. So, we meet people where they are. We tell a story of who we are together and then, we call the community into a new future of hope and possibility. Whether that’s at a university celebration like convocation or baccalaureate, where you’re welcoming new students or you’re sending out seniors who are graduating, or if it’s a time of campus vigils when you’re coming together around a national or global tragedy or crisis, it functions in the same way, right? So, you’re telling the story.

In so many ways, it’s like Marshall Ganz’s theory of public narrative, which helps us learn how to the tell these stories of ourselves, the stories of who we are as community, the stories of “what now?” What action we are called to now. Ritual in its best sense does that. And it can do that when it is rooted in the community that, kind of, births it. So, good ritual and universities ought to be created and shaped by the communities they serve.

For my experience at Syracuse, Wellesley and here at Stanford, that means students. Gathering students in, along with staff and faculty, and asking them, “what has been your shared experience? Where are you in this moment? And what are the challenges you’re facing? And how do we call you next into that?” And I think good university ritual recognizes there are these high moments where everybody sees us, kind of public moments of commencement and convocation and baccalaureate rituals. But there is this opportunity to practice and to do ritual every day that actually shapes and informs those larger traditions. Ritual creates who we are and who we want to be in the world. And so, what are those spaces and places on university campuses where you’re doing everyday rituals that are embodying our shared values and shaping and forming the community into being?

It’s actually my favorite part of doing this work, because we get to, we get to not just tell our stories, but we get to create our stories together and then celebrate them with beautiful art and music and poetry. And there is nothing like standing up in front of one of those rituals and seeing your whole community, all the hopes and the fears and the anxieties, and that release that happens good ritual happens. It’s just great.

>> REV. PAUL RAUSHENBUSH: Thank you. That encapsulates my experience, as well. I was wondering, Dean Magee if you might think of a moment at your time in the chapel at Howard, which is a famous chapel for being just a place where the Spirit filled, when you remember just feeling like, oh, thank God we have this, because it can make a difference. I can imagine many moments of national trauma, as well as national celebration. I’m just curious if anything comes to mind for you?

>> REV. DR. KANIKA MAGEE: The chapel is indeed historic and is one of those amazing and special places. One thing that really comes to mind as we talk about this idea of ritual and significance was when we celebrated the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington. We actually had what I still consider to be a marathon chapel service. It lasted about four hours, and the students stayed. They’re students, right? Even 40-year-olds who are used to long services wouldn’t normally stay that long. But in that moment, they understood the significance of what was happening, that we had before us civil rights leaders from the ages who were there with them. And they missed lunch and the cafeteria closed, and they stayed, because they understood how significant that was. So when I think about, even this moment and the importance of what we do, it is the kind of space that we’re calling the students to stay in, and it’s really the space that they are choosing and saying, even though we’ve been forced to go back home, we still want to stay in this type of space that allows us to experience something that we came to this place for, that’s a part of the collective story of this particular community that, as individual as we are, we still bought into that story. We have invested into that story. We want to be a part and we want our chance to be able to add our piece to that tapestry of the hundred and fifty plus year history of the organization.

What we are struggling with and what gathers us here is really, how do we give them the opportunity to share as a part of that collective, and to be able to center and ground and heal themselves in the midst of it, and to be able to become part of that collective unit of the story of our university.

>> REV. PAUL RAUSHENBUSH: I love that, thank you so much for that, it’ absolutely setting the stage. Dean Soni, one of the things you have spoken about is that you have seen an uptick in participation in some of the events that, when they were in person, were not as well attended. I just wanted to talk a little bit about that and what your experience has been since we were forced to be at distance. And yet people are still striving for this connection to be a part of the tapestry, as was so beautifully said.

>> DR. VARUN SONI: Thanks, Paul. Yes, I think all universities, at least all residential universities, are struggling with similar challenges. The first was how do we move our curriculum online. That’s still a challenge. Professors, students alike are working through those issues of how to provide quality instruction in a remote environment, especially if you moved online midsemester and the class wasn’t set up that way. I think what’s equally challenging, if not more so, is how do you move a community online? Because students come to residential colleges and universities not just for instruction. In fact, so many of the transformative moments of a student’s undergraduate experience, at least, is going to happen outside of classrooms in residence halls, in study abroad programs, in recreational sports, in religious life, Greek life, student government, student newspaper, etc. Those are the communities, the tribes that are life-affirming and nourishing for students, and those of the reasons they come to our institution. How do you with a community online? How do you move that connection online at a time when students need it most? That’s been a challenge we have been wrestling with in religious and spiritual life.

We have noticed that when we move our mindfulness classes online, our yoga classes online, other things we are doing, cooking classes, drop-in groups, workshops, and then of course we had holy week, so Easter services, Passover Seders, now we are in Ramadan, we are getting more students, staff and faculty participating in those online experiences than we would have had in person. We probably have three or four times the number of people taking our mindfulness classes this semester than we normally would have. And we have hundreds on the waitlist. Yes, I do think in this time of uncertainty and anxiety, people are turning to online community to feel connected, to feel like they’re going through this loss of community with someone, even though we are social distanced, the does not mean we have to be emotionally distanced.

I do also wonder if there is a shelf life to this? At some point are we going to be Zoom fatigued – and I’m already kind of there – to the point where we aren’t going to be turning up online for these resources? What gives me some comfort and hope is that this is not just a higher education trend. The pastors I know, the imams, the pundits, the other clerics I know in Los Angeles who had previously had infrastructure to stream services, have also seen a huge upsurge in interest from around the world in their services. It’s not just a higher education thing. I think it’s a human impulse in our times of uncertainty to want to be together. That’s what our faith traditions teach us, to be together, to be there for one another. But the way we’re there was a one another now is to be apart. That is what I think we are trying to reconcile on campus.

>> REV. PAUL RAUSHENBUSH: I want to encourage people in the chat who are attempting to use the chat room to lift up ideas, thoughts, and share what you’re seeing on your campus. This is really intended to be a community conversation. Although we have a lot of brilliance in this panel, I’m really interested in all the brilliance of people participating. I want to talk a little bit about grief and rituals of grief. That’s been mentioned a couple times. I know that there is incredible grief. People are losing loved ones. People are feeling the pressure of being in cities that are enduring great hardship. There is incredible unemployment and economic hardship. I’m wondering, this is an open question for any of you. Is there any way to offer, there is counseling, but can we think of, in addition to counseling, any sort of way to collectively express grief in a time of both sickness as well as economic hardship? Have any of you seen good examples of that? Or perhaps you’ve been trying to create something yourself? I’d love to hear any kind of creativity that has come out of this moment.

>> DR. VARUN SONI: I think for us, we are anticipating a moment where we can have an on-campus, in-person commemoration of what we’ve just been through. Memorializing this period and potentially people we’ve lost in our community, as well. We have been thinking about what that looks like online. To your great point, one of the things I’ve seen with my students is this enormous sense of loss of the end of the year. Especially for graduating students, the loss of commencement and baccalaureate, the loss of all the rituals that end the year, academic convocation, on our campus, the Fountain Run, the other things that students are doing.

Also, the guilt of feeling that pain when students feel like other people have it much worth, we’re not lamenting the loss of life, we shouldn’t feel so bad for feeling bad. I think with my students the conversation has been, no, it’s okay to honor this loss. Commencement is an important life stage. What religion does really well is memorializes these life stages. So, this is a loss and you can honor that loss without that guilt, too. How do we think about this collectively? That’s been a challenge for us.

I have seen this kind of loss of memorialization happen in more intimate contexts, in small groups, mostly online. The pre-existing groups—religious clubs, fraternities and sororities, student government—but, for a campus like ours, with 50,000 students and 20,000 faculty and staff, we are a city within a city, so to think about how we do this collectively online is something that I think we are still working through. And I would love to hear about what other people are thinking about. But I have seen these kinds of grief conversations happen in many different intimate communities, both faculty, students and staff, on campus, just not yet across the campus as a whole.

>> REV DR. KANIKA MAGEE: I will say for us, one important thing, honestly, has been giving voice to it. Acknowledging that there is a tension between what we feel. The truth is, even in the university setting, that there is a tension, there is a need to stop and recognize the global pandemic. Yet, there is also a need to graduate students on time. So, we were in a position of, we can’t just cancel the whole semester. Students are now saying but, it’s a pandemic. We shouldn’t have to focus on class and go online. But the other option was to there would be another semester on the end of your graduation.

Giving voice to the tension that we feel is very important. Because, if we don’t give voice to it, then oftentimes we are left feeling like it’s just me. So, this is just my guilt, because I feel this way and I shouldn’t. That has been a large part for us, is saying some of the difficult things and acknowledging it and just letting it hang out there in the air. Then, giving and creating these opportunities for the conversations to happen. Whether they are smaller groups that have already formed around certain things and making sure that we are being deliberate about it or providing an even larger context for conversations that are not always pleasant. But it at least puts what we’re feeling in our hearts out there, so we don’t have to feel like we’re carrying it alone.

Of course, we’ve done things that are not necessarily creative, but are common, virtual storyboarding and making sure that there are opportunities to put the information and our pictures and our random thoughts, that is one of the gifts and curses of social media. The opportunity to do that, we have constructed new spaces for that. The traditional vigil that we might have normally done at the flagpole is now online. But it’s bringing the ritual that has been normal in our campus to a different format for students to be able to see.

Honestly, I’d say, a large part of what we are also doing is voicing that a delay in some of the physical opportunities to the big things does not mean that they are not going to happen, that we are very deliberate in understanding that, for this class of 2020, you will come back to campus if you choose to and have your day. It’s important to know that, while we are doing a number of things in the interim that are important, this does not mean that it replaces that ultimate opportunity and experience that you were anticipating and hoping for.

>> REV. DR. TIFFANY STEINWERT: I think you’re exactly right; it is that kind of balance between articulating and naming the real grief and loss and not allowing students to minimize it, right? So often they will say, “My grief isn’t as bad as this,” or “How can I be sad about this?” So, naming and articulating it. But also, then pointing and pulling and calling people into a future where life can be different. It is a really hard balance, because you don’t want to weigh too far on one or the other, because then you end up having people feel stuck in that.

I’ve seen some really great things on other campuses where religious and spiritual life departments are putting up breathing walls. So, similar to Kanika’s point around virtual storyboarding, so they are doing that for the whole community. Oftentimes that type of virtual storyboarding is being incorporated into memorials and vigils.

Here at Stanford, we have a great program for grief recovery circles that includes many different departments, Patricia Karlin-Neumann and I, our office is a part of that team that works with counseling and well-being and res life to bring students together in intimate settings to talk about grief and loss. So, we’re doing that.

Another thing that we’ve started doing is helping to embody that articulation of grief by naming it for ourselves. So, by modeling ourselves that we are grappling with our own sense of grief and loss, we invite other people into that. This feels super old-school right now, but we have a blog. And, we invite people from our department, but also from all across campus—students, staff and faculty—to do a daily reflection of about 500 words of where they are in the moment. So, it gives people a glimpse of, here’s how other people are struggling and here’s how they’re managing, here are the challenges and here’s some wisdom you might glimpse in the struggles. I think it’s much easier to model what it looks like to grapple with grief than to give kind of prescriptive, “here’s what you ought to do and here’s how you ought to manage it.” It’s that deep balance that’s hard to strike, particularly virtually.

>> REV. PAUL RAUSHENBUSH: I appreciate these, I think it represents a lot of creativity. I think you’re all kind of minimizing it yet, but it’s all creative and it’s all important.

One of the things I’m interested in is, you know, say next year, we’re actually all able to join together on campuses and do the thing. What do we want to keep? What of this that we have been creative about in imagining would we want to keep? Because a lot of students are spending a lot of time online, some of this they be beneficial. I’m just curious, what pieces feel like, essentially, part of the work as understood next? I am going to sneak in one second part of that question is, to what degree do you balance the reality that your students come from so many different faith traditions, including no faith tradition, that sometimes it’s hard to figure out, as people who sit in religion and spiritual life, how to do that in person. But I can imagine, the nuance of that becomes even more tricky when you’re once removed, perhaps. I want to throw both of those questions out.

I want to also say thank you for all of the great comments that are coming through. We love that. If you have any questions for the panelists, please do use the question format, because we want to start turning towards her questions soon.

Do either of those areas strike any interest in you? What would you keep next year, if you were even able to go back to “normal?” Or a parallel question is, to what degree are you balancing faith traditions and trying to determine what that mix looks like when you have to create rituals in a virtual space?

>> DR. VARUN SONI: From our perspective, I think there are certain things that will now remain online from an administrative perspective, the different offices I manage, I’ve been able to be much more efficient actually, I’ve checked in more. I feel more connected in a strange way than ever have. Meeting every day as opposed to once a week online. I think for business and work processes, there’s a lot we are going to learn about efficient uses of time and resources and commuting, etc.

For student-centric services, there are things we will continue to do. We will continue to do online meditation, online yoga. We know that helps with faculty and staff who might not able to be on campus at a particular time. I’m sure all of our groups will continue to stream online and invite people to participate in various ways, for scriptural study and ritual, etc.

I think there is a flipside to this question too, which is, what do you come back to? Not just, what do keep in a virtual world, but what do you re-embrace in the way we used to do things? And I think, part of this makes us realize the limits of a virtual world. We will reimburse and not take for granted, not that we ever did before, in-person, organic gatherings like baccalaureate and commencement and being together in classes and residence halls.

I’m sure, for all that universities represented here, no one is saying we’re going to go to an online commencement to replace regular commencement. Instead, there will be some virtual acknowledgment of your achievement, but we are going to kick this off until next year. The idea that we are going to do this in-person is so important and it is even more important now that we realize what it is like not to do it in-person. So, I think there are two things, two sides to that. One, some things, we’ll see, should be online, can be online, we have proved the concept, we’ve socialized it and it works. Then, we are going to see that there are some things that should remain in person. We should reembrace those things, celebrate those things, honor those things in ways we might have already done, but I think we do, I think, more emphatically, now.

>> REV. DR. TIFFANY STEINWERT: One thing it’s been interesting for us to think about in this time period is, what’s the difference between physical distancing and relational proximity? Right? So, kind of two sides. Probably before this crisis we would have said that being in community and being close really necessitates being in person. So physical proximity was the same way to think about relational proximity. But what we are beginning to learn is there actually there are ways to foster community in and through virtual technologies. I think Varun is right, it doesn’t replace it, that there is something that we absolutely need about that. But conceptually, for us to think about, what are the building blocks of belonging in community? What creates relational proximity? You could have 100 people in a room and still feel alone. So, but, what’s the difference? How do you do that? Then, how do you bring those two things back together? What are we are learning technologically that fosters relational proximity? Relational belonging and community? What are the things about the way in which we gather in community and in person that also do that? Then out of that, what new rituals emerge? I think it’s a great space of possibility. And, my hope in all of this is that it centers us back to relationships and to community and to belonging.

>> REV. PAUL RAUSHENBUSH: I love that and thank you. I remember speaking to you earlier this year and just talking about, kind of, the epidemic of loneliness. Which happens even when we are on campuses and with people. It’s real. And being clear on the goal rather than the means to the goal is very helpful to remember. Thank you. Dean Magee, do you want to add onto this?

>> REV. DR. KANIKA MAGEE: I agree with everything Varun and Tiffany have said. I’ll just add, I think for us, two things have occurred. One is, there are a lot of little things we did that we took for granted. Now that we can’t have them, we realize how important they are. We spent a lot of time talking, of course, about the big things, the commencement, the baccalaureate. But there are all these other little things that led up to that that we have not ever spent a lot of time talking about. We just did them. For us, it is now a situation of reassessing what are the things that are coming up repeatedly that are now demonstrating to us how significant their value is? And then also, what are the things that aren’t coming up that we had been doing and nobody is seeming to miss those, right? So that we can make sure that we are reevaluating how we assign our priorities. But then secondly, I think the ongoing question is, even as we do the physical things, what are the ways that we can more effectively integrate the virtual pieces into those so that they are some more hybrid opportunities that we have not previously looked at?

>> REV. PAUL RAUSHENBUSH: Thank you. I want to press the multifaith question a little bit, because I do think it’s going to lead into the last question I have for you which is, how do you do a virtual graduation? What plans do you have? But I am interested in this moment, how do you convey the multilayered, multi-textured… It has to be analogous to what you were doing when you were in person. But I’m just, it seems to me a very important recognition that people are going home, or going wherever they’re going, to locations where a very particular tradition is established that may be different than what they were experiencing on-campus. I’m just wondering how you’re balancing those things. Then, we have some great questions I want to get to.

>> DR. VARUN SONI: When I first started this work, I came to campus thinking my job is to support religious and spiritual communities on my campus. But over time I began to realize that the campus, as a whole, was a spiritual community. We are Trojans, so there was almost a religion of what it meant to be Trojan, whether you were theistic or not, religious or not. It connected all 70,000 people from one hundred and forty different countries. It was a shared sense of hope and dream and aspiration. We believe that about forty five percent of our first-year students are not affiliated with religion. So, when we look at the University as a like a civil religion or a secular religious community, it doesn’t just look like a religion. It often does the work of religion—the meaning making, the work of community building, the work of caregiving, etc.

When I think of commencement, for many of our students who have been raised in secular and non-affiliated contexts, commencement is a religious service. What is commencement? It’s ritual, it’s pilgrimage, it’s the intergenerational transmission of values, it’s celebrating ecstasy, it’s being with family, it’s thinking of we, not me, it’s being part of a reality greater than yourself, and it’s acknowledging a life stage. Those are fundamentally religious, sort of, practices and exercises that define us as human being. When students lose commencement, in many ways, they’re losing a religious community or a religious service, even if they’re not religious. It does the work that religion would have done, otherwise.

I think that’s why we are being very careful to say this is not—we’re not doing a commencement ceremony. We are honoring you online, but this is going to be a 20- or 30-minute ceremony with satellite ceremonies that are 15- or 20-minutes. There’s no pomp, there’s no regalia, the white doves, we’re USC Hollywood, we are very theatrical. It looks like a movie set when we do it. Students don’t have that. They don’t even have the change of scenery or families. The day before commencement they will be on their couch. The day off commencement, they will be on their couch. The day after commencement, they will be on their couch. There is no organic marking of this particular time or space because it has that, kind of religious significance that really has to happen, I think, in an in-person environment. I don’t think we are trying to replicate a commencement ceremony online. We are not calling names; we are not technically conferring degrees. We are getting a little inspiration and reflection and we’re gathering people. What I think will happen students will have multiple commencement experiences. They’ll go to their main one. They’ll have maybe, one in their cultural center or their fraternity or their other student groups. They might tune into the Facebook one with Oprah or they might tune into the SSA one—the Secular Students Alliance. There will be multiple ceremonies happening, and students will be able to create their own and engage in their own. But I don’t think they will have a singular experience. It will be this disparate across their different tribes.

>> REV. DR. KANIKA MAGEE: Our community, of course we are planning on having the physical ceremony next year, probably the same weekend that the regular commencement will happen for the class of 2021. But in terms of the online celebrations, honestly, those look very different across our thirteen colleges and universities. There will be a university commencement, and most of the colleges and schools within the university are going to have their individual honors and recognition ceremonies, and they will be calling names, and families will be invited. And they will recognize valedictorians and have superlatives and all of the other things that have come to be recognized as a part of that celebration. So, we really have gathered a number of students for their feedback and what they expressed to us was that the most important part was to hear their name called. Their parents wanted to hear it. Their grandmother and granddad want to hear it. If their name is not getting called, then what are we doing? They wanted to make sure if there was going to be a virtual ceremony, which some of our schools are doing more of a virtual book, um, but for those who are doing virtual ceremonies, that the name-calling was that significant in terms of the experience. We can drop a lot of other things. The talent can go. The graduation speaker can go. But, the opportunity to hear their name called was important. And also, what they expressed with the opportunity to celebrate each other, that they wanted to hear from each other. We normally have some student speakers. They said the guest speaker does not have to come. But we need to speak to each other. That we are experiencing this together. Only we can understand it. And we want to be able to share that moment. And whether that is live, or we have prerecorded things, that was central to their experience.

>> REV. PAUL RAUSHENBUSH: That’s so interesting. At Princeton, at least, we did not name names in the ceremony. My guess is they’re probably not considering that. But as a ritual, it needed to be, it would not be the same for Howard if the names were not named. I think that’s really interesting and important point. And also, so smart of you to go back to students and say, what is essential? It goes back to the point that has been raised a few times—that this is an opportunity to find out what we feel is essential in what we do, and to lean into that even in this moment. Sorry, Tiffany, can you weigh in here about what Stanford is planning and how you feel about it and some of the ways, the process that you have had to develop?

>> REV. DR. TIFFANY STEINWERT: Yeah, so very much like Howard, we are student centered. So, we gathered students, class presidents and part of the student body to be able to say, what is most important, and what students said, kind of resoundingly, through petition at first, because of course, we do lots of petitions, and it was almost the entire class that signed on to the petition. What the petition set is nothing can replace in person commencement. So, we at Stanford have a pledge that we will do an on-site, in-person commencement. We don’t have a timeline for what that will look like. Most likely next year in some way. We know you can’t replace the experience. Much like Varun said, it’s a religious experience in and of itself. It’s one of the high rites of passage in our culture.

But we also recognized, and students said this, too, that on June 14, which is the day students were supposed to graduate, and caps were supposed to fly, we do a wacky walk here, students already had their wacky walks ready to go, that there needed to be something to mark this moment, really for them of grief and loss. And so, we are planning to do a virtual experience that will mark that day. Our President will speak, we’ll tell stories, we’ll share stories. We have an opportunity to begin gathering those, to put them together in some meaningful way, to mark this moment. This is a historic moment. And then to call them and point them toward that future commencement that will be on campus.

One of the lessons we are learning around virtual engagement is this difference between synchronous and asynchronous engagement. It’s really easy to build a video, that was, of course, our first thought, we’ll create this beautiful video. And those are fantastic, and actually, I want to know more about what you’re doing at USC, because that seems fantastic, that you’re doing a celebration video for your seniors. I’m reading the chat as I’m going along. But, we also don’t want students to feel like they’re just tuning in and the president had just sat down and recorded this. We are trying to think about, what would be a meaningful ritual that we could do in time together? So, at—I’m totally making this up, there are no plans so, if people from Stanford are listening, there’s no plans—but let’s say at noon on June 14 we all get in front of our screens and we tune in to this live broadcast. Is there something that we do together from our own spaces? Stoles are very important; do we have stoles for students to be able to stole themselves and then bring those stoles back to campus when we meet together? So, you know, how do we wed together what we really do need to do asynchronously, like these videos and this preparation, and what can be synchronous and in real time? So that again, this idea that ritual is a shared experience, that we can actually create this shared experience. In religious traditions, you might light a candle or ring a chime. What does that experience of a virtual marking of moments look like? We are still in process and we are still being student centered and student led. We don’t have all of the details. We are a later school, so we have the benefit of not having to do this until June.

>> REV. PAUL RAUSHENBUSH: Just visually, I love the idea of seeing hundreds of little boxes of people stoling themselves at the same time. I just feel like that’s actually a memory making event. Not in leu, not in replacing other things, but there is something beautiful about that and deeply connective, so I love that creative thinking.

>> DR. VARUN SONI: One point, on Tiffany’s, like Howard and Stanford, we are hoping to do graduation next year, a year from now. Our graduation is in two weeks, so we are a little early and semester. So just, double book it, so you do 2021 one day and 2021 one day. But, we expect thirty to fifty percent of our graduating students won’t be able to come back for that ceremony. These ceremonies might be THE ceremony, right? Even though we don’t want to replace commencement, we have to acknowledge that this will actually be commencement for potentially half or more of our students. It’s one thing to postpone it and not replace it. But that does not mean a meaningful experience still can’t be engendered and created and embodied. I love what Kanika and Tiffany are thinking through, thinking about, and I think we can all learn from each other. For many of our students, this will be it. Even though we don’t want this to be it.

>> REV. PAUL RAUSHENBUSH: Thank you. Thank you. There was a question from Ellie Thompson about what platforms folks are using for virtual storyboarding. I wanted to, I think, I can’t remember who mentioned virtual storyboarding, but someone did. Maybe it was Dean Magee, I’m not sure, that might have been you? But I also wanted to invite other technology insights that people have gained, perhaps, over the past few months. Are there favorite and perhaps less known than Zoom ways of gathering people that feel meaningful? I would love to hear any tips that you have around that.

>> REV. DR. KANIKA MAGEE: For us, we have been using the group features that the students have, expanding our GroupMes into private jets for them to be able to put information up. We’ve also worked with some of the students to establish some new YouTube channels that they had that are private for them to able to share and us alongside them to be able to share information and to be able to share certain experiences together. We have, of course, used the traditional platforms that all of us have in addition to that. What we are launching this week is going to be a web-based, senior recognition that will have pictures and statements from each of the seniors who want their information to be up. So, we’ve been in the process of gathering that and that will be housed on our website. Then, I will add in addition to that, every year we do a senior Sunday, where the normal chapel service is actually converted into a service in which the seniors get to express what their journey has looked like, and get to share that with the community and construct, really reinvention what a normal Sunday service would look like. And we’re bringing that service online this Sunday and have about twenty-something seniors who will be contributing in different ways to be able to share not just what the last four or five years have look like for them but, particularly, these last two months.

>> REV. PAUL RAUSHENBUSH: Tiffany or Varun, do you have anything to add about platforms that you want to recommend? It’s fine to pass. Nothing comes to mind? Thank you. Thank you. I want to read a question from Professor John Schmalzbauer, who is beloved and known to many of us. His question was, “Many chaplains and deans of religious life look back on 9/11 as a time when they were called upon to create rituals responding to crisis. How is what we are going through different and how will rituals be both online, different in their medium and their content?” Do you ever think of this in terms of 9/11? I’ve heard it come up many times. It feels substantially different in substance to me. But I’m just wondering what all of you are experiencing.

>> DR. VARUN SONI: I was a student during 9/11, so I experienced that in a different context. Although when we did our 10-year anniversary of 9/11 at USC, I was in this role, so we did have a ritual. At USC we did bring a piece of the World Trade Center steel. We worked very closely with the fire department of New York and the 9/11 family commission to bring a piece of steel from the World Trade Center as a monument to first responders on our campus. Every year when we do something on 9/11, we get fewer and fewer people. My students now tell me, “well, we were born after 9/11” or “we don’t remember 9/11.” What seems a little different here is that 9/11 was a single event that had a lot of repercussions. Whereas this global pandemic, we are not sure where the limits are. We are not sure if there is a post-COVID reality. We don’t know, and that uncertainty is what causes the anxiety. The other thing, I think, that’s unique about this particular moment, which might have been true on 9/11, but is certainly true now is that this is a global moment of reckoning and reflection. This is, to me, the most significant religious and spiritual moment of our lives. There’s almost an opportunity here for everyone, regardless of their background or traditions, to have a public theological conversation about our responsibilities to each other, our responsibilities to our planet, what matters to us, why does it matter to us. I think everyone is going through this soul-searching right now. We’re at a time where everyone in the world this month has lost money, except for maybe Jeff Bezos. And everyone in the world has gained time. So, what does it mean to reflect upon this new time? How do we find moments of joy and beauty and gratitude and service amidst the chaos? The whole world has stopped and is wrestling with similar challenges. Not everyone has the luxury to have such existential concerns. There are other real, significant concerns people are wrestling with. It does feel like a shared global moment in a way that I’ve never experienced in my life. I think, like 9/11, we will see new rituals, new monuments, new traditions, new services. But, unlike 9/11, this could be a new normal for us, too, where we aren’t shaking hands anymore, we are social distancing more, we are wearing masks outside. I think it will be different in that way, culturally and in the way that we engage each other. It will impact different students in different ways. We’ve tried to think of the university as an equalizer, a great social equalizer. To some extent it is, when students come in campus, they’re in the same dorms, taking the same classes, we try to create some experiential parity across student groups. But when they go back home, they are back in different places. I have kids of billionaires and I have kids who are undocumented. I have students who can go home and students who can’t go home because of VISA restrictions, or because of Muslim travel ban, or whatever. It will affect people in very different ways, even in terms of their ability to come back to school. That will also shape how we memorialize what this has meant for us. We are just going to be in the consequence, and in the way this manifests for longer, and that uncertainty is what causes so much anxiety. Whereas I think after 9/11, we didn’t know what the future lay, but we could immediately memorialize 9/11 in a way we could not immediately memorialized COVID, because we are still in it.

>> REV. DR. KANIKA MAGEE: I will add to that, I think we will see, certainly, some differences in how members of our world community are perceived, much as we saw after 9/11. There were certain communities that were ostracized. We’ve already seen that in this case. I will say, in addition, one of the differences is, the way that this situation has once again highlighted the socioeconomic divide within our nation, that that was not the same situation that we don’t with post-9/11. I often reflect on, I was a graduate assistant actually in the chapel at the time 9/11 happened, and I reflect on one student. Because we were in D.C., so the Pentagon was very close, and a student said, “I heard the police sirens and for the first time, as a black man, I knew I didn’t have to be concerned that they were coming looking for me, or to do something to me.” There was a sense that this situation was not connected to the racial, economic, social divide that our community often experiences. For the COVID-19, when we consider the differences in how school systems are reacting to this, public, private, wherever community, when we consider the difference between those who are in situations where they have to go to work or they can telecommute, when we consider the difference in the infection rates and the mortality rates based on what communities look like, this is one of those that is very clearly different depending on where you come from and what you look like and how much or family makes. So, for me and certainly for our community, that is a big difference.

>> REV. DR. TIFFANY STEINWERT: I think this crisis has laid bare all of the fissures in our social fabric. We think about COVID has kind of unmasked those who had privilege prior to this. But, the reality is that inequity was a pre-existing condition here in America. These ills, these inequities, these disparities in health and poverty across race and class, this has always been with us. But now, we have this moment where we have a global experience of what the impact or the consequences of this disparity is our own communities, across the country and around the world. I think the question for religious and spiritual life communities particularly on college campuses is, how do we engage students in thinking critically about this experience? For those whose communities and families have always been marked by these inequities, they know this reality. This is not new. For those on our campus for whom this is a revelation of something they didn’t quite understand or get yet, this is an opportunity for them to think critically about what and who we want to become in the future. This is a moment of opportunity, it’s a moment of choice that each of us has. We often talk about “being undone” by COVID. Our systems are breaking. It doesn’t work anymore. We worry about higher education or the banking industry. All these things we are think of as coming or being undone. I don’t think that’s necessarily bad. Let me say, there’s horrible and awful things happening, but the opportunity for us in religious and spiritual life on college campuses is to help our students think critically about how we rebuild. We don’t and we should not rebuild in the image of what was before. We ought to be thinking about, what are the creative and new ways that we can rebuild, recraft, reimagine so that the centuries old systemic inequalities—that we design them out of existence, right? That’s a totally idealistic and utopian vision. And I think that is actually what we are actually called to point people toward in religious and spiritual life. I think it’s a great, in my language I would say it’s a kairos moment, a moment of opening opportunity. There’s an incredible loss, there’s going to be an ongoing-ness of living in the shadow of death and that will be a real. It goes back to that balance. But for us in religious and spiritual life, we ought to be designing rituals from here on out that constantly point out, unmasking the unjust and pointing toward new ways of being. It’s a hard task, but I think we can do it. Actually, I know we can do it.

>> DR. VARUN SONI: I just want to reiterate something that Tiffany said. I love this idea of not rebuilding the world that we lived in but reimagining the world of the future. I think that is something that religions have and continue to do, but that’s also something that universities are in the business of doing too. So, I think the conversion of spiritual reflection and a research university. We have these unique communities that can really, not just reimagine, but rebuild those futures. We have students want to do that work anyway, that’s why they’re at the universities they’re at.

>> REV. PAUL RAUSHENBUSH: Thank you. I want to thank all three of you for this rich conversation. Beautiful, inspiring, and also great information sharing, as well as all of you who are present and offering great questions, as well as information sharing in the chat.

I love the way the conversation ended today because it really, when I think about commencement, it’s like, what are we going to send forth the students with? What is the great charge? What have we equipped them to do? And, how do we want them to be part of the building of what is next? That is that, we want to send students forth with a mandate to do the work. And what you, all three of you have articulated is a beautiful summation of the work that is in front of us.

I want to thank all three of you. I want to thank everyone who joined us. And we are looking forward to more opportunities to be in conversation with all of you in the future. Thank you very much for being part of this conversation.