We Live In Different Worlds, I’ll Leave It At That

February 9, 2021

Kenji Kuramitsu is a clinical social worker, writer, and spiritual care professional living in Chicago , and a 2020 Interfaith America Racial Equity Fellow.

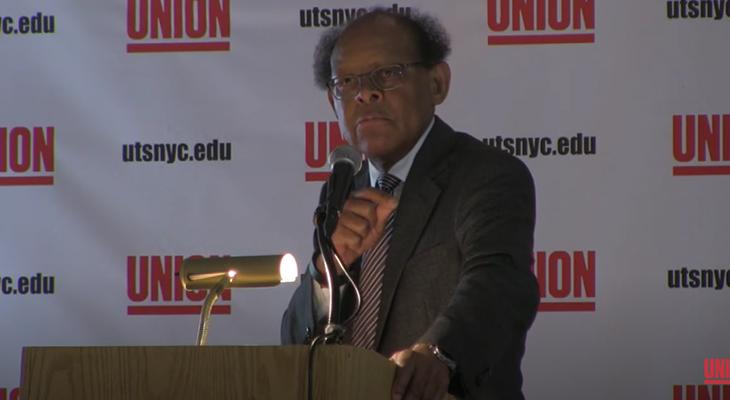

In February of 2016, a lecture hall at New York City’s Union Theological Seminary swelled with students, professors, and community members. I joined a livestream of the event from my home in Chicago, excited to participate virtually. The occasion was a lecture by the late theologian James Hal Cone. Cone, whose presentation was called: “The Cry of Black Blood: The Rise of Black Liberation Theology.” Rewatching the talk five years later, Cone’s prescience is powerful – though the Trump Presidency was still nearly a year from its inauguration, Cone brought pastoral and prophetic sensitivity to his concern for the accelerating acts of white racial violence that have long characterized our national life.

Following his address, a familiar scene unspooled: during the question and answer component, a white man stood and offered what we might call “more of a comment, really.” The audience member accused the professor of being divisive and myopic, prompting the event’s moderator to intervene with a startled response. The room bristled with chilled umbrage. All eyes turned to Cone for his response, which he delivered with significantly less passion that I was expecting:

“We live in different worlds. I understand what you’re saying, I really do. But we live in different worlds. I don’t know what can help you … I’m okay, you know? I don’t have much longer on this earth. I don’t have much longer. I just thank God for the ministry. It’s my calling, my calling. Everybody has a calling … I’ll just say: we in different worlds, and I’ll leave it at that.”

There were a million ways Cone could have responded, most of them righteous, some of them thundering. I was struck by the note of resigned faith that Cone offered. He did not try to drag this man kicking and screaming into the Truth; nor did the professor try to contort himself into the warped image of his interrogator.

This exchange has replayed in my mind often over these past many months. The man shouting accusations may be a stranger in a public forum online or off – more commonly for some of us, he may also be a peer, a parent, a spouse, a relation. Our glowing maps color states red or blue, yet they cannot begin to chart the cleaving apart of families, of communities, of neighborhoods where these divisions are most acutely felt. Some fortunate folks are spared the tax of those you love living in this different world. We may at least feel empathy for how maddening it must always feel to be locked in eternal status with a sincerely deluded interlocutor.

Standard bearers in politics, journalism, even psychoanalysis have taken up a literature of etiology, seeking to diagnose our shared malaise. Some advance a white identity politics of resentment located in the “forgotten” rural areas – J.D. Vance revitalized this genre with his now-maligned Hillbilly Elegy. Centrist journalists, among them Ezra Klein, have characterized these divides in the language of the increased polarization that has marked the past several years: gender, race, climate, medicine, policing, the areas of disjuncture are many and the potential catalysts of conflict are legion. Most recently, psychoanalyst Jeanne Safer offered a practical contribution to this literature of division: I Love You, But I Hate Your Politics: How to Protect Your Intimate Relationships in a Poisonous Partisan World.

Rural/urban divide, polarization, approaches to connecting across political difference, these theories capture some deep truths about our predicament – yet in other ways they misapprehend the tenacity and resilience of white supremacy in our common life.

Madness may be a better marker than division. Sontag’s study of “illness as metaphor” gets us closer to hewing language for the racial crisis some have called “a pandemic within a pandemic.” What else can we call this but madness when a quarter of the folks who live in the United States believe that the 2020 election was unjustly stolen. When a fascist siege upon the Capitol building is justified, when vaccines, protests, pizza, are anti-Semitic conspiracy.

Cone seemed to offer a theological response to bridge this precipice. It is the rare psychosis that can be broken by an appeal to rationality. His tactic is not panacea: there are times when other responses are more than warranted. To stand up for one’s own dignity and to fail to be cowed by the terrible madness of the aggressor. By contrast, Cone’s liberative theology might endorse a range of responses: protest, worship, arts. The Black freedom movement has indeed employed these and other approaches in the face of cruelty and inhumanity. Cone also models how at other times, one might simply offer a weathered recognition that we are simply too far apart to have a healthy exchange or a full relationship.

What might creative opportunities for interfaith collaboration look like in light of the ways that racism and madness so endure? Role of liberative theological commitments and movements in our midst. What does it mean to live across these worlds, or to be in relationship with those who are? What is the role of interfaith work in building this kind of world? Like most sincere supplicants, I pose the question out of desperation, exhaustion, anticipation.

Share

Related Articles

American Civic Life

We Commemorate, We Commit: Out of Catastrophe, a Conversation on Connection and Repair

American Civic Life

Is This a Time for Bridgebuilding? 5 Leaders in Conversation

American Civic Life