Powerful Voices: A New Look at the Rabbi Who Marched with Martin Luther King

January 14, 2022

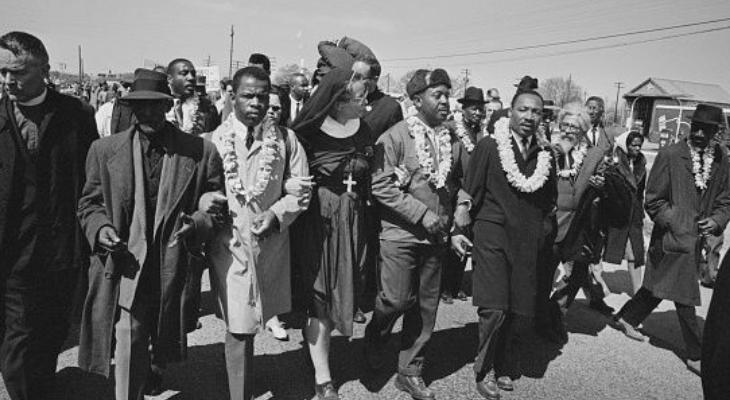

The 20th century rabbi and scholar Abraham Joshua Heschel is well known to many American Jews. The author of a poetic meditation on the meaning of the Sabbath, Heschel vocally and visibly supported the civil rights movement and the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The image of Heschel marching alongside King in Selma, pictured above, remains iconic not only for Jews committed to King’s legacy, but to all who see the power of interfaith coalitions in the ongoing efforts to secure voting rights and equity for all citizens.

In his new biography, Abraham Joshua Heschel: A Life of Radical Amazement, Princeton University historian Julian E. Zelizer looks at this influential orthodox rabbi through the eyes of a political historian interested in political coalitions, how they take shape and what lessons they offer for faith-based movements today. Zelizer writes that before Heschel ever set foot in Alabama, his book “The Prophets” – a fiery treatise that painted the biblical voices for justice as “religious warriors for morality” — had resonated with King and other clergy who saw in the biblical prophets the moral urgency that sustained their own efforts to fight injustice. By the time King returned to Selma with an interfaith coalition of marchers, King strategically wanted the white-bearded rabbi up front, knowing the power the interfaith image would have in the national media and to politicians watching from Washington, D.C.

In honor of Martin Luther King Day, Interfaith America managing editor Monique Parsons spoke with Zelizer about Heschel’s legacy, his friendship with King and the lessons their lives hold for today. The conversation has been edited for clarity.

Monique Parsons: As a historian, you’ve written so much about people like Newt Gingrich and other polarizing political figures. Can you tell us what attracted you to this project?

Julian E. Zelizer: Definitely there’s a personal element. I come from a family of rabbis; my father is a conservative rabbi in (New Jersey) and my grandfather was a conservative rabbi in Columbus, Ohio, and then Florida. Judaism is also just important to me. Heschel was someone I grew up hearing about, seeing the photographs, and I was just curious about who he was. A second reason, though, connects to my research. I wrote a book a few years ago on Lyndon Johnson and the Great Society, and one of the themes that I started to look at as I did the research was the role of religious groups in civil rights movement politics. I became very interested in and I was impressed with the impact that not only the Black church, but also other kinds of faith groups and places in the country like the Midwest, were having in pushing politicians toward a stronger civil rights position. And then finally, a lot of American Jewish history, which I read occasionally just for my teaching or my own interest, some of it’s insular. It doesn’t connect the figures that are being studied to broader elements of American history. And my doing it, in some ways, was a great way to look at what this theologian from the Jewish Theological Seminary could tell us about the big stories of Europe and the role of religion in Cold War America, to the antiwar movement during the late 1960s.

Share

Related Articles

American Civic Life

American Civic Life

Faith Based Efforts Work in Vaccine Uptake: Now Let’s Make it Easy

American Civic Life

King’s Last Full Year of Life: Protest, Praise, Ire, Incarceration

No single religion in the end has the same kind of power as collective groups that bring different faiths together.

No single religion in the end has the same kind of power as collective groups that bring different faiths together.

MP: Were you surprised at any point during your research?

JZ: When you study Heschel superficially, there’s the Heschel who was the writer and who wrote books such as “The Sabbath,” and then there’s the Heschel of the ‘60s in the photograph in Selma, this activist who looked like a rabbi or a prophet. And what was really surprising and interesting, the more I studied him, was how these were connected. Ultimately, Heschel was not just a Jewish person who became a progressive activist. It was really a deep understanding of Judaism and his theological arguments that led him to see that not being on the streets, whether it was fighting for civil rights or against war, was in some ways morally and spiritually wrong.

MP: I’ve also seen that great photo from Selma, which is so inspiring. But the relationships and the networking and the writing that led to that moment, and then what happened afterwards, it is just as inspiring.

JZ: That’s exactly right. He’s an immigrant, he grows up in Warsaw, and so there’s this question: how did this person who grew up in a small Jewish neighborhood in Poland end up being someone who the national press was covering in all these political fights? It was not inevitable that’s where he’d end up. You know, this is coming out of World War II; 6 million Jews have been killed and entire communities and institutions in Eastern Europe had been wiped away.

MP: Tell us about Heschel’s relationship with Martin Luther King. A 1963 conference in Chicago was pivotal. King invited Heschel to come and give a speech.

JZ: Heschel had really been following civil rights politics. As early as 1958, he’s calling on rabbis to stand behind this growing movement, but it’s in January 1963 that he and King and the movement really become connected. King is holding and putting together with some other figures an interfaith conference on religion and race, and they invite Heschel to be one of the keynote speakers. Heschel gives a very powerful speech which got a standing ovation, where he offers some of the toughest words you can probably read about race and religion, arguing that people who say they’re religious and are racist are not religious, that the two can’t coexist. He calls racism Satanism and blasphemy. King really pays attention to what he’s hearing, and he’s very taken by Heschel and he’s taken not only by the message, but the way he invokes the Hebrew prophets and biblical ideas in a way many other liberals who are not religious didn’t at the time. And the two also hit it off personally. They both are students of philosophy. One of Heschel’s closest friends is Reinhold Niebuhr, who King greatly admires and reads all the time. Both are married to musicians. They spend time together in Chicago, and the relationship takes off from that moment, and it never really stops. They’re in frequent contact. They participate through the ‘60s, not just in Selma but in different sorts of events. King is even influenced by Heschel, he becomes more interested in the issue of Soviet Jewry, in large part because of Heschel, who’s a very strong proponent of this issue before it’s actually a big issue in the Jewish community. And that relationship lasts until King’s assassination and Heschel will be at the memorial and funeral proceedings in Atlanta at his death.

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, left, presenting the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. with the Judaism and World Peace Award, December 1965. (Library of Congress)

“Interfaith America with Eboo Patel”

MP: You note that King and Heschel were together when King gave his first really strong public statement against the war in Vietnam.

JZ: That’s a big moment. This was in the spring of 1967, in April. King had given some low key speeches where the media wasn’t there, raising questions about the war, but he had been very hesitant to condemn Vietnam. Many civil rights leaders supported the war. Many more were scared of angering Lyndon Johnson, who had been a strong supporter of civil rights. So there was pressure on King not to do this. In the end, he says he can’t be silent, and he decides to make his first major public address at the Riverside Church in New York. And it’s at an event that this group of interfaith preachers that Heschel had helped create, and was one of the leaders of, was putting together. If you watch the old video footage, King is right next to Heschel, and it’s interesting in that this was the setting where King finally felt comfortable, saying the words that so many civil rights leaders didn’t want to him to say, a really stinging speech about Vietnam. It’s a really important moment of interfaith cooperation and in their relationship.

MP: Who fills those shoes today?

JZ: After the ‘70s, the religious right, the Moral Majority, were the dominant force on the public stage, and this is how we think of politics and religion — from a rightward perspective. There were many progressives and liberals who were tepid about engaging with religious leaders or religion, which they saw as being too close to what was going on in conservative politics. Many others were just more secular in their outlook. But there are some voices who I’ve been listening to and following with interest. One is William Barber, who’s a Protestant minister, who has been part of the Poor People’s Campaign and something called Moral Mondays. And he’s a forceful voice on every issue from fighting poverty to voting rights. Another in the Jewish community is Jill Jacob of Truah, which are rabbis who fight for human rights, both in the United States and all over the world. I don’t think they have the kind of presence we saw in the ‘60s, but I think that they trying to. They’re out there.

MP: You reflect a lot about Heschel’s ability to take religious language and inspire people to take action. Does that kind of language still have power today, when we see more and more people unaffiliated with any religion?

JZ: Yes. I still think when religious leaders speak, they have amazing power. First, there are many people in the country who are still very religious, and even if people move away from (religion) as adults, the language still resonates in some ways. When it’s brought to bear on the social questions that matter to all of us, I still think it can have incredibly broad reach, in some ways broader than secular progressive rhetoric. When a leader like William Barber speaks to an audience of hundreds of activists, the people who are not really connected to religion still think the language has a certain kind of moral and ethical clarity that everyone can really be energized by and respect. And it’s a clarity that’s important in terms of reaching political leaders who obviously think primarily of their own interests in maintaining power. The religious right has shown what this can do in terms of political coalition making, so there’s no reason liberals couldn’t experience the same.

We live in this age where political dialogue is so broken, and there’s so much vitriol. By connecting to what the Bible says, or to what scholars say from a religious perspective, it’s a great way to get lay people in this country to really think in deeper ways about these political questions.

MP: How powerful can interfaith coalitions be, and do you think Heschel’s story provides a good model for work that can happen today?

JZ: It’s a really an essential model. It was controversial often when he did it. There’s often a resistance to interfaith activism, although I think it’s become more accepted over time. But I think no single religion in the end has the same kind of power as collective groups that bring different faiths together. What it does is elevate the whole debate (and consider) what does any kind of religious perspective leave you on a question like the war in Vietnam, or today, how you think of January 6? And practically, the thing about interfaith is that each faith has incredible reach, there’s a kind of organizational power that brings to bear in terms of members, bringing people out to rallies, or communication through newsletters, through social media and email. It’s unbelievable. That’s the big lesson from the period that I studied for today about how essential these really are.

MP: You pointed out that most religious groups in America didn’t oppose the Vietnam War initially. But Heschel’s group managed to build influence.

JZ: This group, Clergy and Laymen Concerned about Vietnam, starts in October of 1965, and at the time, the antiwar movement was basically nothing. Most Americans supported the war if they were paying attention at all. And in both political parties, there wasn’t much support for antiwar activists. It’s only in ‘67 and ‘68, at the end, where you really see the antiwar movement nationally. So this group of religious leaders is at the forefront, and I think that was significant. They help give a kind of legitimacy to a movement that many saw as radical . I write about how when they have these mobilizations in Washington, and they bring religious figures to Washington to march, they’re also meeting with national security advisors and politician. That’s a remarkable example of what religious interfaith religious activism has achieved.

MP: One of my favorite scenes in the book is when you describe Martin Luther King and William Sloane Coffin going to Heschel’s apartment to mark the end of Shabbat. They light the Havdalah candle, they smoke cigars. It feels very relaxed.

JZ: I love that story. They’re at his apartment, and they’re doing the end of Shabbat. And they’re hearing stories and fables, and then drinking a little once the day came to an end, and the personal connection between these different leaders was very strong, very intimate, and I think an important part of what came out of the activism. It’s not just that interfaith activism is important, but it also nurtures these very strong personal connections, which can just lead to more things.

MP: Thank you so much for writing this book and for speaking with Interfaith America.