How a Pluralist Views Democracy’s Beautiful, Messy Tensions

November 7, 2022

How do religions change and make change in the world? For Brie Loskota, these are more than questions to ponder in a classroom. Loskota, born in the Philippines and raised in a Pentecostal Christian family, has built a career devoted to religious pluralism and civic engagement. Among her many projects, she’s built a leadership training program for young Muslim civic leaders, an app to help first responders navigate the needs of religious communities during disasters, a public radio series of COVID sermons, and more.

Loskota is now the Executive Director of the Martin Marty Center for the Public Understanding of Religion at the University of Chicago School of Divinity, a role she took on last year after leading the Center for Religion and Civic Culture at the University of Southern California.

As part of Interfaith America Magazine’s “Vote is Sacred” series, Loskota sat down with managing editor Monique Parsons to talk about voting, Election Day, and the ways religious communities can serve as bridges during polarized times.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Monique Parsons: When you think about voting and civic engagement, do you make a connection to your own worldview or religious leaning?

Brie Loskota: I was born in the southern Philippines, in Cebu. My parents were there because they were pursuing something that I call the reverse American dream — they left the U.S. for economic opportunity and upward mobility. My dad went to medical school in the Philippines in the ‘70s. When we returned to the United States, they raised us in this very strongly Pentecostal environment. And to me, Pentecostalism meant sort of global engagement. We went to a big Pentecostal megachurch, and then some offshoot churches growing up, and I went to a big evangelical Christian high school, which I hated. I’m American, but I wasn’t born here, so (I’m sensitive to) that concept of who belongs and who’s foreign. And my mom would always pick up anybody who was in my dad’s department who was an immigrant, who was visiting, who was kind of displaced in some way, (and) they would always be at our house for dinner. She would always try to make them feel welcome. And she would always just repeat, “You were strangers in a strange land,” and “Be kind to the stranger.” And that was very much the rhythm of how she talked, in the cadence of her thought about how you engage the world.

So, (for me) there was a little bit of this disjuncture between this, like white conservative evangelicalism of the suburban high school that I went to, and this kind of engaged notion of what it meant to be a stranger in a strange land and how you’re supposed to behave. And I was also a rebellious teenager. So I went to college, and I wanted to build race cars. I wanted to be a petroleum engineer with a race car business on the side or something like that. And I took some history classes I really liked, so I declared a history major. And then I took a religion class I really liked, and I declared that as well. So, when I was thinking about going to graduate school, I had to take his Jewish study classes to finish my major, and one of my professors said I should apply to Hebrew Union College. I was the only non-Jew (there) and I ended up writing about Muslim and Jewish relations.

It was really my first time being on the inside of an institution that I wasn’t a part of and wasn’t built for me. I had to learn a really fantastic set of skills that people who are “other” have to learn really instinctively. And I thought that was powerful and magical and wonderful. I ended up doing a bunch of stuff with people who weren’t like me in many ways, but I learned how to like and love them. It was really a profound experience, and that’s been the kind of trajectory of my life.

Share

Related Articles

American Civic Life

American Civic Life

Is This a Time for Bridgebuilding? 5 Leaders in Conversation

American Civic Life

The Interfaith Legacy of Muhammad Ali: “The Wise Man Changes”

MP: How do you connect living in our participatory democracy to something in your own faith or worldview? And I’m curious how you’ve seen people of other faiths do that, too.

BL: In every sense of the word, I’m really a pluralist. I don’t adhere to anything. I also don’t really feel foreign in anything. And so that feels really wonderful. I was on the board of a Jewish anti-genocide organization; I built the Muslim leadership institute; I built a center focused on Black church economic development. I spent seven years evaluating Catholic sisters’ development programs all around the world. I border-cross and get to be in places and be in relationship with people that are profoundly different from me. I spent seven years working with Catholic Sisters and really love them. They’re phenomenal. So, I feel indebted to and informed by a rich host of religious traditions, and not in a way that I like, woven into my own, but in their own deep particularism. I really like the things that are deeply particular because I think it’s the only way that you can connect to anything that feels universal.

I’m just a little bit too Gen X to join anything. I don’t really want to be a joiner, but I want to I want to be at home in lots of places. So that’s my religious sensibility and values, and it’s very deep and true. So, what I like about democracy is it’s a really, deeply frustrating thing, because if you do it right, you don’t win all the time, right? So, it means that you have to practice habits of being in relationship with each other and being committed to something larger than your own purposes and goals. And so in many ways, it’s an interesting tension between the hubris to say, “I should make decisions,” and the humility to say, “My decisions have to be in tension with other people’s decisions and values.” And I like tension. I think it’s really interesting.

There’s a line from Langston Hughes I quote a lot: “O, let America be America again— a land that never has been yet—”

When I think about the potential, what it means to create a country where people are free, and they’re obligated … what a wonderful tension, right? That’s potentially at the heart of democracy — individuals — but we’re also community.

I think about voting in the same way they think about jury service. Our dominant way of engaging anything is either as owner or consumer: I either own something, or I’m served by it. And voting enables us to be a part of a system that belongs to us, but it’s also obligated to us. It is made for us, and it’s also larger than us. And I just, I love that. It’s really messy, and in its name, people can do awful and terrible things. And at the same time, without our engagement, and without our participation, those awful and terrible things are only made worse. So there’s like a positive upside of this kind of beautiful project that was trying to come together and have ideas clash against each other. It’s by no means a perfect system.

We live in a world of tensions between two myths: One is of nostalgia, and one is of utopia. I think either of those makes democracy dysfunctional. I’d love a new myth. I don’t know what it is, but it’s something deeply human and deeply struggling.

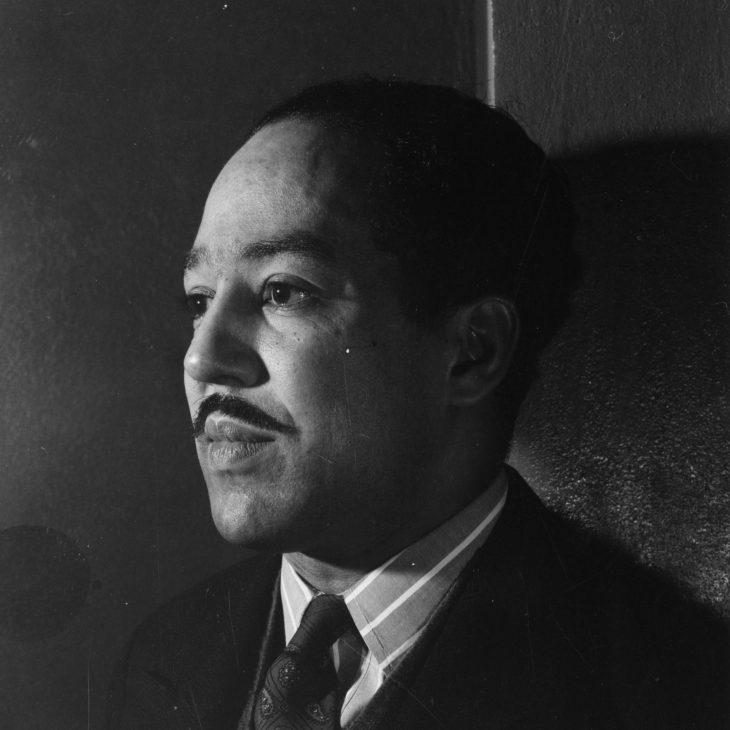

Brie Loskota

Brie Loskota directs the Martin Marty Center at the University of Chicago School of Divinity. She has deep and broad experience in building strong organizations and networks; expertise in advising foundations, governments, and the media; and a research agenda which explores how religions change and make change in the world. Prior to joining the Divinity School, she served as the Executive Director of the Center for Religion and Civic Culture at the University of Southern California. (Photo: Tarik Trad)