Faith and Fear on the Frontlines

May 7, 2020

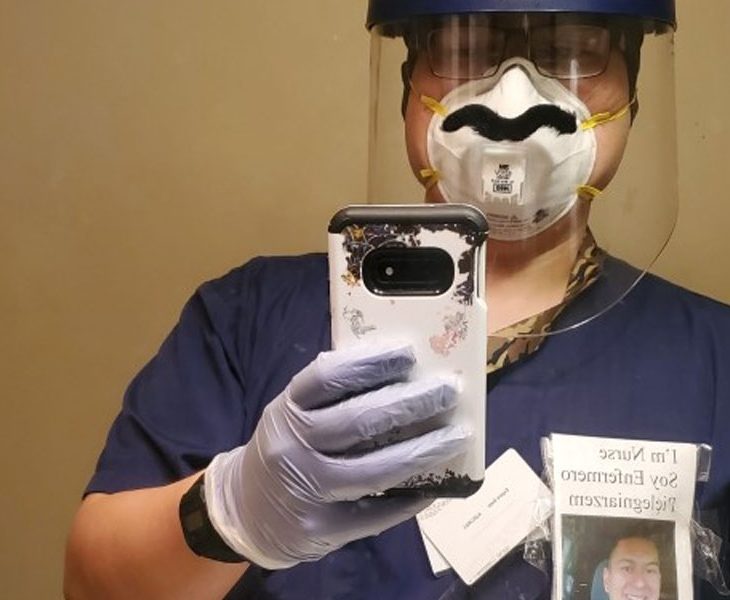

When Enrique Pina looks in the mirror, he barely recognizes himself.

He is dressed in navy-blue scrubs with three-quarter sleeves, his wrists double layered with latex gloves, and a big blue helmet sits atop his head with a clear plastic shield trailing down from its ends to cover his face and neck. Under the shield mask, Enrique is wearing a pair of glasses and a white n-95 mask, while the stretchy yellow elastic on its sides cut into his cheekbones and jaw.

Enrique works as a registered nurse at a nursing home for the elderly in Chicago. Though the facility was supposed to have 11 certified nursing assistants (CNA) to care for the patients, most of them quit amidst the Covid-19 pandemic, because they were feeling overworked and underpaid. Enrique is one of the three nurses who show up to work daily, which means on average he takes care of 32 patients, some of whom have the virus. Recently, he started feeling the symptoms himself, and is waiting for test results to confirm if he has the virus.

“My wife and I are both worried about our lives,” says Enrique. “But if God brings you to it, God brings you through it, that is my mantra while facing dark obstacles.”

To date, the US has 1.24 million confirmed Covid-19 cases and more than 73,000 deaths. As healthcare workers around the nation struggle with overwhelming work schedules, rising cases, and lack of proper medical gear, some, like Enrique, are using their faith to calm their fear and offer help to others in moments of crisis.

“I am a Unitarian Universalist and I’ve always been spiritual. In these times, I’ve prayed to God to protect me and save me, and in return, I have promised to always be a force of good and light,” says Enrique. “My experience working with people from different faiths has given me perspective in working with people towards a common good.”

Before he walks into the room to meet his patients, Enrique adds a few embellishments to his gear—a fake mustache on the mask, a sticker of an astronaut meditating in space on his helmet, a printout of his selfie – his face smiling warmly at the camera – stuck on top of his shirt with the words ‘I am nurse Enrique’ written in English, Spanish, and Polish and a smiley emoji.

He points at it when he greets his patients, whose faces are marred with confusion and panic, and he says, “Good morning! I am your nurse for today. I am sorry that I am in full gear, as you know this whole place is a little crazy with the virus. I want you to know that this is my face, that I am your nurse, and that I care. Please let me know how I can help you today.” He smiles as he sees his patients relax, some smiling, some laughing at him, “Faith, prayer and laughter get me through depressive moments and allows me to stay calm and deescalate crisis situations.”

Rabbi Dena Trugman is a chaplain at MossRehab in Elkins Park, Pennsylvania. The first thing that happens when she arrives at work is the temperature check at the entrance. She then swaps her cotton home mask for a surgical mask, cleans her hands with sanitizer and sits at her desk to make phone calls for the rest of the day.

“A big part of my role as an interfaith chaplain involves in-person conversations with patients and their families,” says Dena. “About 60-70 percent of my work relies on body language and visual clues, so it’s a huge learning curve for me now to pick up on those things over the phone and learn how to be there for them and pray with them from afar.”

MossRehab is home to many long-term patients who suffer from brain trauma and spinal injury, and many of the phone calls Dena makes are with families who have not been able to see their loved ones for months. In the light of the pandemic, they are not sure if they will ever see them alive again. “Having someone to talk to about their fears, anxiety and the uncertainty of what we are going through brings them some peace.”

Philadelphia is one of the worst hit cities by the virus, with more than 16,000 confirmed cases and over 800 deaths. Healthcare workers everywhere are overwhelmed by the influx of patients.

Dena walks around the building to check-in on her colleagues. Sometimes she’s greeted with a sarcastic, “I’m great! This is all fine,” while other times they share their fears and anxieties with her. Some healthcare workers are pregnant and are worried about how working so closely with sick patients might affect their health, while others are stressed about carrying the virus with them to their families. Others open to her about their grief of losing coworkers to the virus and the helplessness they feel when they’re unable to save a patient or tell them with certainty if they will be okay.

These conversations stay with Dena as she admits she has her own fears about the pandemic weighing down on her mind, and has prioritized the need to take care of herself as well, “When I’m not at work, I tune in to meditation videos or podcasts to take my mind off things.”

Victoria Psomiadis is a resident physician at the University of Kansas Medical Center where she has been treating Covid-19 patients since the crisis began. Like Enrique and Dena, Victoria’s patients are filled with panic, fear and many questions: When will they be allowed to go home? Is there a vaccine available yet? What’s going to happen next? How long will the lockdown last?

Too often, Victoria doesn’t have the answers.

“It’s scary to be a doctor and in a position where you don’t really know what’s going to happen. But as an orthodox Christian, I tell myself that God has given me a gift and I know what I am meant to do with this gift – save lives. So, I wear my mask, my gloves, and I say a little prayer before I enter the hospital – that’s all the safety gear I need,” says Victoria.

She remains calm in their presence, communicating what she knows, helping them connect with their families through Zoom calls, assuring them that they are going to be okay. She sees patients being wheeled in and out of ICUs day-in and day-out. Outside the room, she groups together with her coworkers, discussing patients’ health, rejoicing when a patient recovers and goes home—grieving when they don’t.

“The fear we see around us is palpable,” says Victoria. “I am worried about my own health too. I am often scared if my mask is on right, if I should clean my hands again, if I missed a step and am going to fall sick. But I know that God has a plan for me, and faith is a part of everything for me.”

Enrique, Dena and Victoria are all alums of IFYC trainings and continue to bring Interfaith leadership to their vocations and communities.

Share

Related Articles

Higher Education

American Civic Life

Faith and the COVID-19 vaccine: ‘Muslims were among the first to believe in vaccines’

American Civic Life

Faith and the COVID-19 Vaccine: ‘Using the Black Church to Get the Word Out’