Amy Coney Barrett and the American Wars of Religion

September 29, 2020

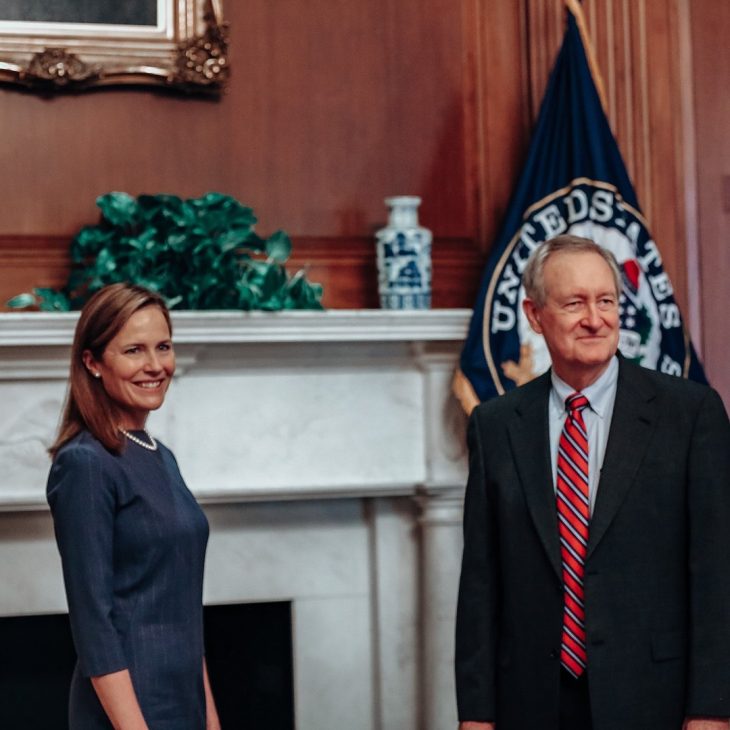

Amy Coney Barrett’s nomination to the Supreme Court is sure to touch off another battle in the long-running American wars of religion.

Many Democrats, who just days ago were highlighting the role that Judaism played in Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s worldview, will cast suspicion on Barrett’s Catholic faith with lines like Senator Feinstein’s, “The dogma lives loudly within you.”

Republican supporters of Judge Barrett, including those who barely paused to pay respects to the pathbreaking Ginsburg, will no doubt cast themselves as champions of religion, even though many of them were quite happy to go along with Donald Trump’s Muslim ban.

The tragedy is that support for the ways that diverse faith and philosophical convictions shape American public life in general, and a range of political actors, in particular, should be a matter of bipartisan pride. Indeed, it is a signature quality of our country.

The United States is the world’s first large-scale attempt at a religiously diverse democracy. Of all the various forms of identity that we speak of these days (race, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, class, disability, and so on), religious diversity may be the one that the European Founders came closest to getting right. These (generally) wealthy, (loosely) Christian, (presumably) straight, (most assuredly) white male slaveholders managed to create a constitutional system that protected freedom of religion, barred the federal government from establishing a single church, and prevented religious tests for office.

Religious language has given the United States some of its most enduring symbols (“city on a hill”, “beloved community”, “almost chosen people”, “better angels of our nature”, “new Jerusalem”, “new Medina”), and is the inspiration behind many of our most vital civic institutions, including hospitals and colleges, disaster relief agencies and food banks. If you woke up tomorrow and discovered that all the institutions founded by religious communities in your town had disappeared, it would be unrecognizably different, and far worse off.

Share

Related Articles

The idea of dignifying diverse religious identities and encouraging them to make positive contributions to the nation was enacted, in part, as a strategy to avoid a reprise of the European Wars of Religion on this continent. As James Madison wrote in The Federalist Papers, “The degree of security … will depend on the number of interests and sects.”

The idea of dignifying diverse religious identities and encouraging them to make positive contributions to the nation was enacted, in part, as a strategy to avoid a reprise of the European Wars of Religion on this continent. As James Madison wrote in The Federalist Papers, “The degree of security … will depend on the number of interests and sects.”

Sadly, religious diversity gets short shrift in our educational system. In an ambitious study of diversity issues in higher education by my organization, IFYC, in partnership with Professor Matt Mayhew at The Ohio State University and Professor Alyssa Bryant Rockenbach at North Carolina State, we discovered that while somewhere between 2/3 and 3⁄4 of college students said that they spent time learning about race, nationality, and sexuality, fewer than half said that they spent time learning about religious diversity.

If they had, perhaps they would have seen some interesting commonalities between Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s Jewish faith and Amy Coney Barrett’s Catholic experience. One such commonality is the manner in which both of those traditions were excluded from public and political life a century ago. America did not always live up to the ideals of our European Founders when it came to welcoming religious diversity. Indeed, a fierce Protestantism often violently excluded both Jews and Catholics from public life and political power, making a Justice Ginsburg or a Justice Barrett a virtual impossibility a century back, on account of both their gender and their respective faiths.

It was a civic organization called the National Conference on Christians and Jews that emerged to battle anti-Catholicism and antisemitism. In the educational programs they spread throughout American schools, communities, and military installations, they referred to America as a Judeo-Christian nation. The phrase is neither especially theologically precise or historically accurate, but rather was a genius civic invention that accomplished dual goals: highlighting commonalities across Judaism, Catholicism, and Protestantism, and reminding Americans of the ideals of the nation when it came to welcoming religious diversity.

There are now as many Buddhists in the United States as ELCA Lutherans and twice as many Muslims as Episcopalians. We are long past being a Judeo-Christian country and are now fully Interfaith America. No doubt an individual from one of these communities, or perhaps a Sikh, a Baha’i, a Hindu, an atheist, or an individual shaped by indigenous traditions, will one day be nominated to the highest court in this land. This individual might cite her convictions as inspiration for liberal political views, or for conservative ones. Perhaps she will belong to the equivalent of a praise group that is known for what might be called charismatic forms of worship – these certainly exist in Hinduism, Islam, Buddhism, and indigenous traditions the world over.

By then I hope that Americans will have developed the interfaith literacy about their own nation and its remarkably varied citizens to welcome whatever religious or philosophical conviction the nominee brings, and focus their fights on politics rather than faith.