One Educator’s Mission to Make Colleges Care about Religious Diversity

March 3, 2022

Dawn Michele Whitehead is the Vice President of the Office of Global Citizenship for Campus, Community and Careers at the American Association of Colleges and Universities, an organization dedicated to improving and supporting undergraduate education around the world. Whitehead and Janett I. Cordovés, director of Higher Education Partnerships at IFYC, recently published “Interfaith Cooperation for Our Times: Educating Citizens for a Diverse Democracy.” The publication focuses on the Interfaith Leadership in Higher Education Initiative, a partnership between their organizations that aims to broaden, deepen, and strengthen commitments to interfaith teaching and learning at colleges and universities.

Interfaith America Managing Editor Monique Parsons spoke with Whitehead recently about what inspired her to become an educator, develop her expertise in global citizenship and interfaith education, and focus on building better student experiences in higher education. The conversation has been edited for clarity.

Interfaith America: How did you get down this path? How did interfaith work in higher education became such an important focus for you?

Share

Related Articles

American Civic Life

Faith Based Efforts Work in Vaccine Uptake: Now Let’s Make it Easy

American Civic Life

Eboo Patel and Wajahat Ali: Is “Interfaith America” Even Possible?

American Civic Life

Is This a Time for Bridgebuilding? 5 Leaders in Conversation

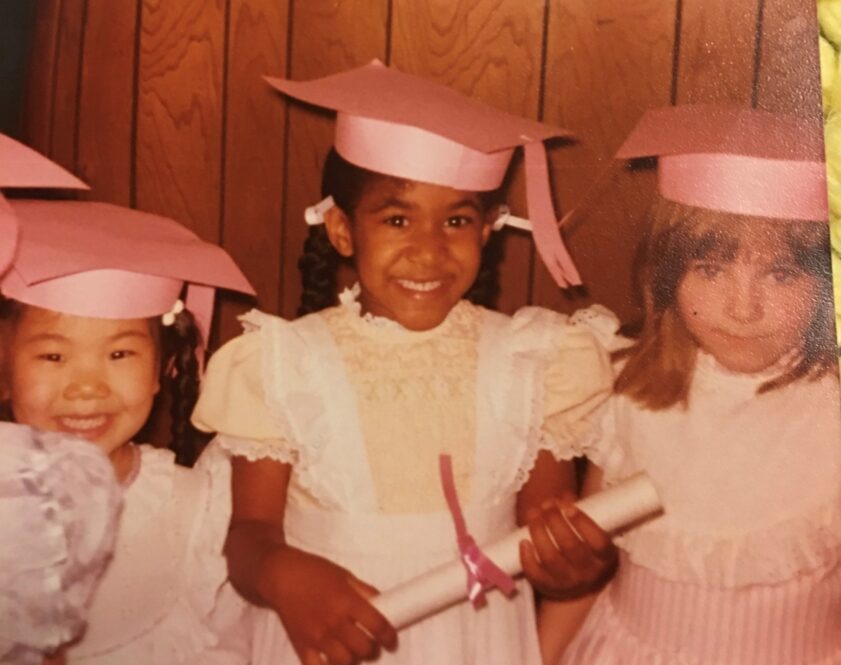

Photo courtesy of AAC&U

Dawn Michele Whitehead: I could start from childhood. My parents did a really wonderful job of cultivating in me an interest in learning about other people. My mom recently found a picture of my kindergarten class, and in it there were kids from all over. There were probably five or six Black kids, a few Latino kids, some Asian American kids, some white kids, and I had kind of forgotten that, because of my elementary years, the rest of the years, I went to a school that was predominantly white. But my parents always had me involved in activities, where I was learning about from different people and different religious groups. I was in a children’s choir. We sang in synagogues, we sang in churches, I went to Europe and sang at a cathedral. I think that foundation that my family had, in making sure that I was aware of the world broadly, but I was also aware of my community and the many different people that were in and of my community.

I grew up on the north side of Indianapolis, Indiana. It really was a wonderful place to grow up. There was a vibrant Jewish community. There was a long history of a Black middle class in the area, not necessarily in our area, but in the city of Indianapolis. Madam CJ Walker and other wealthy black folks lived in the area. Growing up, I was in this group called The Culture Club at the Children’s Museum of Indianapolis. I was able to go and learn about different cultures in the “Passport to the World” gallery, and we were able to see artifacts. So long story short, I think I had that foundation of being interested in learning about difference. It could be a faith tradition; it could be a cultural issue.

Dawn Michele Whitehead (center) in Kindergarten. Photo courtesy of Whitehead

And then when I did my undergrad at Indiana University, I spent a semester on the Navajo Nation. I did my student teaching there. My major was History and Afro American Studies at the time — the name has changed, of course. And I also had an anthropology minor. I had the opportunity to engage and learn about differences, including faith traditions. My mom was a nurse, and she had a friend who was a conscientious objector. He was a member of what I believe is called the Old German Brethren Church. They live with very few modern innovations. At the time, they didn’t have cars. They didn’t have electricity, and it was part of their religious tradition, and so for my anthropology class, we had an assignment where we could go and learn about a different culture and spend a day with people. So my mom wrote Steven a letter because they didn’t have phones, and my mom, my dad, and I, we all go and I spend the day working with them, cooking and working on their farm.

I would just say that interest was always there. Same thing as much on the Navajo Nation, I learned so much about the Native American church. On the Navajo Nation there are so many religions. I was based at a school in Utah, about 12 miles from the Four Corners. The Navajo Nation spans New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah. It was an amazing experience. I learned so much about different cultural practices, different faith traditions among the community. I think all of this laid the foundation for my interest in the world.

And then I was a classroom teacher. I taught high school multicultural studies and U.S. history. You can’t teach those classes without bringing your students in. I had a fair percentage of Indian American students. All of my students were welcome to do presentations and had opportunities to explore their own cultural heritage and faith traditions in class, and several of my Indian American students came in and told us about different aspects of their family practices, how it connected to broader trends and issues.

I think I’ve just always had that interest, and I’ve always wanted to share it with my colleagues to help us understand how we can get along. One is just being part of a community and how we can understand each other and knowing that we’re limited if we try to explore and understand the world only through our own lens.

I love Indiana. I’m a Hoosier through-and-through. But if I didn’t leave Indiana, or if I didn’t learn perspectives from outside my community, I would be in trouble. And I think that sort of is the framing that my parents directly gave me, and then I was able to make connections professionally.

IA: I’d love to learn more about your parents. What shaped their worldview?

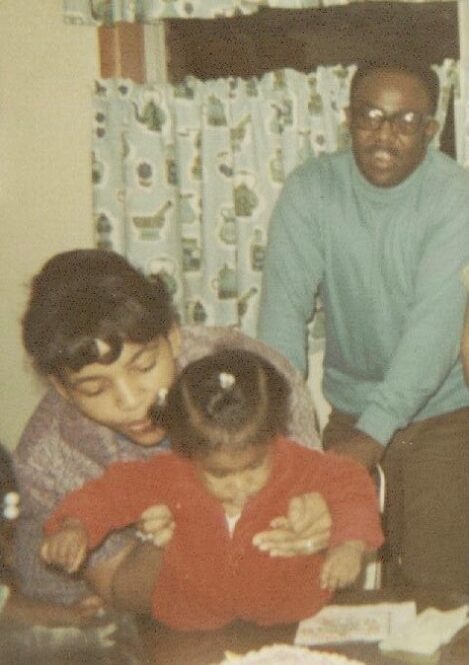

Dawn with her parents, Edward E. Whitehead and Paula Whitehead. Photo courtesy of Whitehead

DW: They’re just regular Hoosiers. My dad was from Madison, Indiana, a very small town. He was the first black baseball player at Indiana University, and I think he just had an amazing perspective about people, about relationships across racial lines. He had that experience of being the only, and the first on the team, and all of the challenges he faced when they went to the South. They had the ‘gentleman’s agreement,’ and the Southern teams wouldn’t play if they had a colored player — the word of the day at the time — it really just gave him this perspective that people are people, not that there aren’t differences and we don’t acknowledge those differences, but that people are people and we treat people equitably. He experienced that, and he knew that that was not the way to be.

My mother was from Indiana as well. She went to an integrated high school in Indianapolis, a pretty well-known high school. She was a nurse, and she just cultivated our interest. My grandmother was the same. You know how every generation wants their children to do better, not just better in a financial sense, but just do better? You know better, you do better. My mom appreciated those opportunities. She was the one who said, “The choir’s going to Europe? You should go!” I sold Girl Scout cookies. I sold enough cookies to go to Canada, and both my parents were like, “You want to go? Okay, great!” They just were those kinds of parents that realized that there was a bigger world out there, and that I needed to be prepared for it by engaging.

IA: Tell us about your work with interfaith education, why it’s needed and how you’ve seen it evolve over time.

DW: I taught for a few years, and then I went back to graduate school, and I did my PhD in International and Comparative Education and African Studies. I did my dissertation research in Ghana, and spent most summers of grad school in Ghana, and then I went to Indiana University, Purdue University, Indianapolis, to serve as the Director of Curriculum Internationalization, and I also taught some courses in Global and International Studies. You just find that it’s important that you understand and are connected to interfaith cooperation and interfaith agreement. My students would marvel, many of them. I had a summer study abroad program in Ghana. I remember one year, I was there with students, and Ghana is mostly Christian, especially in the South, and they have a sizable Muslim population in the north. And so every day on one of the main TV channels, they would say, “It’s time to break your fast,” as part of Ramadan, and the students were like, “This is so odd, because at the school, all they do is sing Christian songs!” I was helping them understand coexistence, and this is something that’s important to our whole society. No, I’m not a practicing Muslim, but I can acknowledge it, and it’s important that our society recognizes this is something to respect.

In the work that I do now at AAC&U, most of my work is focused on global learning and integrating global perspectives, global experiences, for students, and civic engagement. You can’t do that work if you don’t have an interfaith understanding or interfaith underpinning. That’s, for me, what is most important because I think if we’re talking about engaging communities, if we’re talking about engaging the world — and I’m a proponent of global learning happening locally, as well as internationally — the interfaith dimensions are so important. As we prepare students in the classroom, and we prepare students from a diversity, equity, inclusion perspective, we are finding ways for students to have these conversations and see the commonalities that they have.

IA: When you talk about bringing that global perspective locally, can you give an example of what that looks like?

DW: Absolutely. One is simply letting students know that global does not equate international. Sometimes when we have students thinking about international experiences, it limits and it means only those that can be mobile, only those that can leave the country. But when we look at things from a global perspective, we’re able to look at those global implications and to look at the ways that we’re connected, whether or not we leave the country. So, we may talk about the issue of child poverty, and that’s an issue that affects children all over the world. It may look different in different places, but because it impacts all of us, we should look at different examples in different places to understand how we combat these issues.

Another example, students in one of my Global and International Studies classes, they worked with a local organization that worked with resettlement of refugees, and so my students were working with high school students, the children of refugee families, as they were seeking to apply for college. My students would talk them through the process of applying for school, and they were able to learn about folks from different parts of the world. Some people would say they really needed to go and have an experience in Ghana, or they really need to go and have an experience somewhere else, but they could have a global experience in their local community. We’re seeing more and more institutions that are doing this type of work. They’re working with global communities in their local communities, or they’re using interactive video conferencing to make those connections.

IA: How did you first connect with IFYC? This project each year has invited interest from more universities and colleges who say this is something we want to learn from and implement.

DW: There has been a longstanding relationship between AAC&U and IFYC for many years. We’ve had those connections as institutions. And then when Lynn Pasquerella, our president, and Eboo (Patel, IFYC president and founder) had conversations, and we were thinking about ways that we could really work together more intentionally, this idea of working on a summer institute that aligned with an existing summer institute came about. We started working together to figure out what would this look like? How can we do this? How can we build on an infrastructure that we already have in place, but enhance it, and make sure we are able to focus on the interfaith pieces?

IA: It’s been five years now, and what progress have you seen? We hear a lot about the divisions on college campuses, but please tell me what you see.

DW: We are seeing such a counter narrative, if you will, and seeing students intentionally coming together to look at these issues. I think one of the things that for me made it even clearer why this is important, as a number of our institutions, as they were finally — and I say “finally” depending on the context — addressing the racial reckoning that we were having in society, you saw this coming about from interfaith organizations on campus, and students on campus from different faith traditions, saying, “Yeah, this is not okay. Why is this happening? We need to come together and help push our campuses to reconcile and to make sure that we are doing the right thing in terms of this horrible racial history, and the discrimination, and the systemic issues that we’ve seen.”

“Most of my work is focused on global learning and integrating global perspectives, global experiences, for students, and civic engagement. You can’t do that work if you don’t have an interfaith understanding or interfaith underpinning”

“Most of my work is focused on global learning and integrating global perspectives, global experiences, for students, and civic engagement. You can’t do that work if you don’t have an interfaith understanding or interfaith underpinning”

I’ve seen a number of institutions where the students are encouraging this and demanding that their institutions do this work, and they’re finding some really interesting ways to do it. At the University of Denver, we had a colleague there who created an app for religious holidays. Now that may seem like not such a big deal, but she was able to do it, or their team was able to do it in a way that everyone at the institution could just download the app and click, and it would be activated on their calendars. That that may not seem like a big innovation, but if you can say, okay, we’re going to have all of our academic advisors have these religious holidays on their calendars, that makes a huge difference. The other piece they did that made the biggest impact is they started developing these tools that provided quick information for faculty and staff about religious holidays. So it would say, is this holiday celebratory? Is this solemn? What do I say? Do you say “Happy Easter”? Or someone might say, “Happy Diwali” — do you say that? And then also they had something in there about modifications, like will students perhaps need to miss class? People could have some expertise, and feel, “Now I know.”

IA: What have been some of the challenges?

DW: I know some folks, when I was mentoring teams (at a university learning institute), that would say, “Oh, well, we don’t do interfaith stuff.” And I was like, “What do you mean by that? Do you have students?” You can look at multifaith studies, you can look at interfaith traditions, you can look at religious studies, and then we talk about the co-curricular models of how you are engaging students to talk about, and think about, and do things across difference, including interfaith traditions. We share examples of different events and activities that some of our institutions have put on, how institutions have worked alongside their diversity, equity, and inclusion offices, to think more strategically about how interfaith connects to that work, too.

Whitehead leads an interactive workshop with educators. Photo courtesy of Whitehead

IA: Can you think of an example of the intersectionality between the DEI offices and the campus life or chaplains’ office or the interfaith offices?

DW: It depends on how Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion office is situated. In some institutions, the diversity office was created to focus on compliance, and that would include looking at affirmative action issues and equal opportunity. So I think, in some of those cases, there may be resistance. There may be that sense that that’s not on our checklist of what we do. On the other hand, you have other offices where you we have seen that collaboration coming in, and that’s from the intersectionality of the students. We may say, yes, you’re focused on serving these particular student groups, but their faith traditions, or lack of faith traditions, are part of that student identity, so you must consider those kinds of things. We’ve seen some that have done joint programming, where they have offered programs or expanded their offerings to address interfaith cooperation and education. We’ve seen others where they have also engaged with the international office. There was some institution that did a Thanksgiving meal where students brought food from many different traditions, and they could be religious traditions or cultural traditions.

IA: With the publication of this resource on interfaith education, do you hope this work will be something that continues to grow across the field of higher education?

DW: Yes, I do. We’ve structured the publication to address, are you looking at this from an equity, a DEI perspective? Are you coming at it from a curricular perspective? We hope people can go and focus on their area, and hopefully they’ll read more. The other piece that’s really, really important, is to help institutions see that this is part of the overall institution’s broader goals. At colleges and universities, we talk about our student populations, and this includes working with students from different faith traditions or those that don’t have faith traditions. And so just as we are saying that international or global is something that’s important for all of our students, just as we’re saying the civic mission is important for all of our students — they need to be community-engaged, community-minded — that (engaging religious diversity) is also something that’s just as important. I think the more examples we can show of ways that we have integrated this work through the curriculum, through the co-curriculum, then then that really makes a huge difference. That’s our ultimate goal.

IA: What gives you hope? And what is happening on the campuses that do this well?

DW: The payoff to me is improving the experience for the students. Sometimes we can get caught up in our own academic or administrative areas, our areas of expertise. But I think when we go back and think about the benefit for the students, we see that this improves the student experience, one, in terms of their sense of belonging. I think it also improves their preparedness for careers.

One member of our cohort was Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University. They’re preparing people to work in the aviation industry that is inherently global and inherently connected to faith traditions. Imagine you’re looking at a long flight and your job is to choose what kind of meals are you offering. Are you offering halal? What are your options, or did you even think about that? Just seeing all of the spaces in areas where people are able to recognize the value and importance of interfaith both inspires me and gives me hope, because we’re seeing more and more different types of institutions thinking about these issues.

Dawn Michele Whitehead recently joined IFYC’s Director of Higher Ed Partnerships, Janett I. Cordovés, in conversation for “The Interfaith Imperative Engaging Religious Diversity in Higher Education” webinar – listen or watch here!