Black Americans Crave a Deeper Integration of Religion and Politics

April 16, 2021

Throughout the Qur’an, God charges the faithful “not just to be nice and avoid doing wrong in their personal lives, but instead, to support the good and prohibit or resist that which is incompatible with al-sharia (the Path). This mandate, which is repeated over and over again throughout the Qur’an (e.g. 3:110 & 114, 7:157, 9:71 & 112, 31:17), has two distinctive characteristics: First, it is active rather than passive: believers are called to take action, rather than merely permitting or refraining from certain behaviors. Second, it is social rather than personal: enjoining and prohibition are actions which occur in the context of communities, undertaken with others, and for the sake of others.”

The Gospels are quite similar to the Qur’an in these respects. Most of the time Jesus discussed religion per se, it was to criticize performative religiosity, condemn those who profiteer on religion, or to denounce those who adopt a dogmatic and inhumane approach to religious faith and practice that misses the forest for the trees. Overall, his message was directed primarily towards how the faithful should act in the world – particularly, how they should engage with their fellow believers, and others who are vulnerable, suffering or oppressed. In short, the Gospel of Jesus is fundamentally social in its orientation.

These are not features unique to Christianity or Islam. Scriptures and faith traditions near-unanimously include messages about how society should be ordered and towards what ends, about the duties and responsibilities people have towards one-another, to the divine, and with respect to various earthly authorities. Therefore, to define religion primarily in terms of ‘personal’ beliefs is to misunderstand the character of religion entirely (for instance, beliefs about appropriate gender roles, family structures, sexual relations, about whether trans women are women – these structure how people interact with one-another in profound ways. Such beliefs can radically change, and indeed have radically changed, the course of societies).

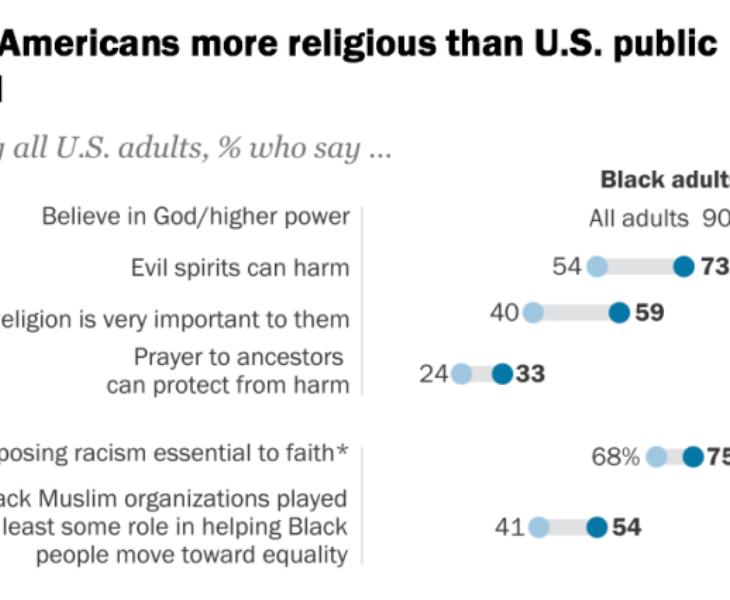

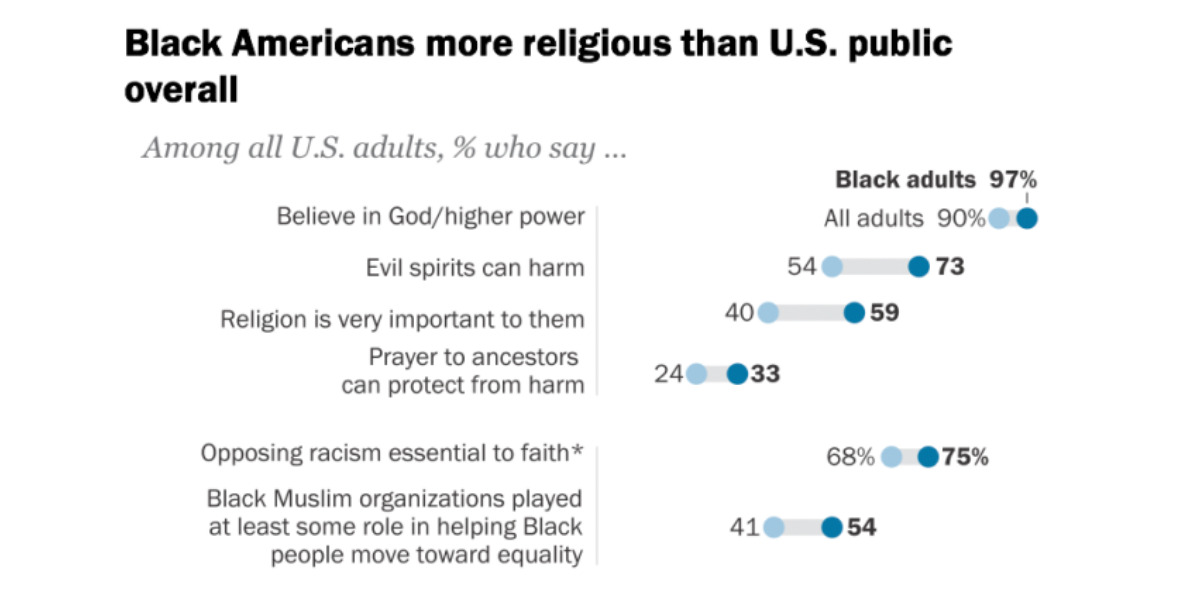

Within the United States, black people seem to be particularly attuned to the political nature of religious faith. They are significantly less likely than whites or Hispanics to think that churches and houses of worship should stay out of politics – and much more likely than other racial groups to assert that religious institutions should express views on social and political questions, or even political candidates.

More than other religious congregants in the U.S., black people report that sermons within their places of worship touch on issues like voting, political participation and organizing, crime and criminal justice reform – and much more than most other Americans, black people view it as ‘essential’ or ‘important’ for places of worship to offer sermons on political topics. Not only do black places of worship touch on politics more, they help drive political and civic participation: African Americans who attend religious services are much more likely to volunteer in their communities, attend public hearings or neighborhood meetings, and to contact elected officials as compared to those who don’t attend religious services.

Black Americans describe combatting racism and sexism as essential to their faith, and recognize black churches as vehicles for promoting equality and helping the vulnerable and needy. African Americans report that their religious communities help them establish a sense of agency and control of their lives, even when they feel politically powerless.

And yet, black Americans, especially young people, have become significantly less likely to identify with organized religion. They have also become significantly less likely to belong to a church, mosque or synagogue: in the period from 1998-2000, 78 percent of African Americans belonged to a religious congregation. In 2008 – 2010, it was 70 percent. In the period from 2016- 2018 that number had dropped to 65 percent. In the period from 2018 – 2020, it was 59 percent. Although black Americans remain significantly more likely than whites and (especially) Hispanics to be a member of a church, synagogue or mosque, the gap between blacks and whites has been shrinking, because the declines have been sharper for the former than the latter.

Share

Related Articles

Critically, these declines to not seem to be driven by disbelief in God. Polling shows that virtually all black people continue to believe in a higher power. Even blacks who affiliate with no religion are more likely to believe in a higher power, and to pray somewhat regularly, as compared to most other religiously unaffiliated Americans. Even most black atheists and agnostics say they believe in a higher power other than the God of the scriptures. Most non-black atheists and agnostics do not hold such a belief.

If unaffiliated African Americans continue to hold religious beliefs, and even engage in religious practices – why are they abandoning organized religion? The changing relationship between religion and politics may be a significant driver.

Again, non-black Americans tend to be much more insistent in a separation between religion and politics. When preachers push political views that are inconsistent with their partisan affiliation, they tend to abandon the faith, and often seem to elevate politics in the aftermath as a replacement for religion.

For African Americans, the opposite dynamic seems to be at play – many may be leaving because contemporary black churches are not political enough. This is not to say that most black congregants are ‘woke’ and want church to reflect the kinds of politics that dominate academia or prestige media outlets. Most black people aren’t down with that, and it is a problem that ‘the discourse’ on race in America seems to be out of step with the values, priorities and perceived interests of most African Americans.

Nonetheless, although most black people aren’t terribly preoccupied with the kinds of questions that dominate the attention of woke elites, they do want their religious leaders and institutions to be out front in helping to address the social problems they have to reckon with in their day to day lives. Yet, there has been a shift within black churches in recent decades – a pivot away from the social gospel and towards the focus on individual faith and prosperity characteristic of many sectors of white Christianity.

African Americans seem to be growing increasingly alienated from religion as a result of this abdication of leadership on the part of faith leaders – they seem to reject the apparent complacency and lowered ambitions of contemporary religious institutions. Frustration over these perceived failures seemed to be particularly acute during the contemporary campaigns for racial justice and the COVID-19 pandemic, leading many to explicitly question the continued relevance of black religious institutions for the times we are living in.

And yet, strikingly, when black people leave the church, they become significantly more likely to vote Republican. Again, this is the exact opposite of the trend for whites (who become much more likely to vote Democrat after drifting from religion).

Indeed, at the same time we see growing disillusionment with respect to organized religion among black people, there has been growing alienation among African Americans from the Democratic Party too. As I put it to NPR in the aftermath of the 2020 election:

“It is a glaring indictment of the Democratic Party that in the midst of a global pandemic and economic crisis that disproportionately affects women and people of color, so many minority voters did not believe that their lives would necessarily be better off under Joe Biden than Donald Trump… There’s hardly a better indication of Democrats’ inability to speak to ordinary people about things they care about than this — in the midst of the milieu we find ourselves in, the multiple crises Trump ineptly presided over, Democrats nonetheless managed to lose vote share with minority voters.”

The black church and the Democratic Party have long been strange bedfellows – and it looks like growing shares of African Americans are losing faith in both institutions, viewing neither as sufficiently responsive to their values, priorities and interests.

In a previous essay, I demonstrated that religious Americans of most faith traditions shifted dramatically towards the GOP over the last four years; I argued that these trends across religious denominations may help explain the significant gains Republicans made among voters of color in 2020. However, to the extent that unaffiliated Americans are likely to drift towards the GOP, the 6 percentage point drop in religious affiliation among African Americans over the last four years may have played an important and underexplored role the observed political trends too.

Looking forward, to the extent that African Americans continue to stray from organized religion, they may become more politically heterogenous as well – especially if the GOP decides to actively court these constituents, instead of their current strategy of attempting to suppress or neutralize our votes (under the assumption that we will almost invariably cast our ballots for Democrats… although actually many Democratic states are terrible on voting rights too, including Joe Biden’s home state).

As I’ve explained elsewhere, it would likely be a great thing for racial justice if black people’s votes were considered ‘up for grabs,’ with both parties trying to court us and speak to our priorities — instead of the current dynamic where the Democrats largely take black voters for granted, relying on GOP boogeymen to scare us to the polls while they try to court white swing voters – even as Republicans have largely written us off and try to minimize our political impact.