What Does Faith Have to Say about the COVID-19 Vaccine?

March 12, 2021

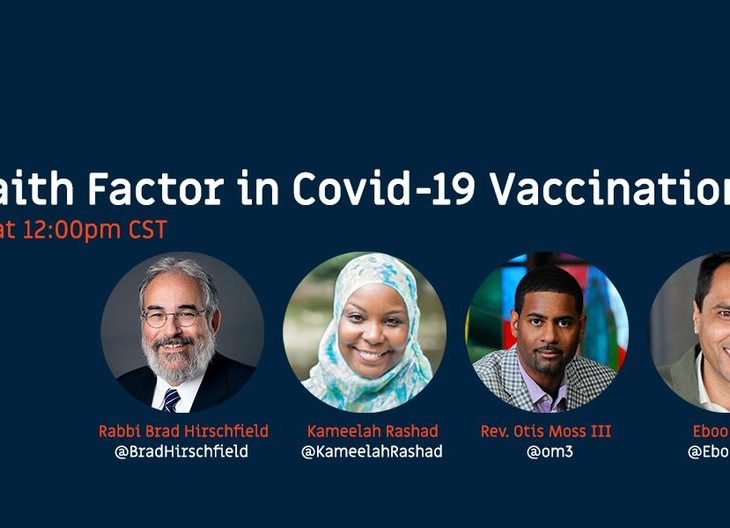

Four national religious leaders joined IFYC’s Founder and President, Dr. Eboo Patel on March 10th, to discuss the crucial role that faith communities are playing in fostering far-reaching and equitable vaccinations against the COVID-19 pandemic.

Rev. Otis Moss III, the Senior Pastor at Trinity United Church of Chicago, offered insightful commentary: “If you take COVID-19 and compare it to COVID 1619—the original American pandemic—you put those two together and, you have a disaster and a tragedy.” He went on to share about the authentic relationships Black churches have built within their communities and how this has forged an opportunity to be a trusted information-sharing regarding COVID-19 vaccination.

Kameelah Rashad, founder and president of Muslim Wellness Foundation, and founding co-director of the National Black Muslim COVID Coalition discussed the relationship between science and religion: “There does not have to be a dichotomy between religion and science. I think the wonder that we find within the scientific world, for me, is a manifestation of the majesty of God.” Framing scientific discovery as a manifestation of the divine is an important language in building trust in the COVID-19 vaccine among religious communities.

Rev. Jim Wallis, the founder of the Evangelical and social justice-focused magazine, Sojourners, places an emphasis on the intersection of faith and politics: “We have been in conversation, even yesterday with the White House and what they are saying is it’s not whether faith leaders should be involved. It’s how. How do we do this?” His answer? Making offerings that can help transform the way we do healthcare such that it also rectifies and heals systemic racism, making vaccination more accessible for marginalized communities.

Rabbi Brad Hirschfield, President of Clal–The National Jewish Center for Learning and Leadership, on the pitfalls of theological framing: “…there is no master narrative theologically that will convince other people. Because I don’t think the question is fundamentally theological. It is a matter of trust. And trust-building is very different than policy advocacy. Even though they are both in the sacred categories.”

We invite you to read the transcript below or view the full conversation in all its richness as we work together to address some of the most pressing issues of our time.

Share

Related Articles

American Civic Life

Faith Based Efforts Work in Vaccine Uptake: Now Let’s Make it Easy

American Civic Life

As Vaccine Mandates Spread, Employers And Colleges Seek Advice On Religious Exemptions

American Civic Life

Check out more interfaith resources on COVID-19.

Transcript

Eboo Patel: Good afternoon, Salam Alaikum, and Ya Ali Madad to all of our friends joining. A huge thank you to our terrific panelists today. These are people I consider friends, colleagues, mentors, shining lights on the road to Shalom. The reason I use the word “Shalom” is because one of interpretations is wholeness. Today we’ll be talking in so many ways about wholeness. The role that faith communities and faith leaders like the ones we have with us play in our spiritual care, and they also play in our physical and our community care. There is in Islam a frequently used phrase, “deen and dunya,” the spirit life and the physical life. And in Islam, as in all faith traditions, both of those dimensions of our lives are very important.

I want to say welcome and thank you to Reverend Jim Wallis, to Dr. Kameelah Rashad, to Rabbi Brad Hirschfield, to Reverend Otis Moss. I want to say in a personal way, I can’t imagine a more critical role in our world this past year, and this next year, than faith leader, right? You have taken care of people’s physical selves. Even and after the point of passing into the next world. You have provided spiritual care over screens. You have sat in suffering. You have done laments. I want to say a huge, huge thank you. Those of us who view ourselves as followers of your congregations, in some ways literally and in some ways figuratively, we appreciate the light that you have cast. Thank you so much. We begin a new dimension of this journey, of this virus and Insha’Allah, God willing, the end of it, which is in vaccines. Today we’re going to be talking about what it looks like for people of faith to believe in the scientists and the other healers who have developed these vaccines. The distinctive role, the distinctive attitudes that various faith communities are bringing to the vaccine and the distinctive role of faith leaders and faith communities in advancing efforts for Shalom, for wholeness, for deen and dunya, for the life of the spirit and our physical and material lives as well.

I’m going to first turn to my friend, Reverend Otis Moss III, who is not only senior pastor at Trinity United Church of Christ, but who did a great interview with Krista Tippet recently on the great Howard Thurman and who was featured in Skip Gates’, “The Black Church” on PBS with just a powerful, powerful opening sermon. Otis, my friend, it’s been a while since we’ve seen each other physically, even though we live in the same city. I think about you often. I appreciate you. I want to ask about how COVID has affected the lives of your congregation. As a bit of a follow-up question, what role is your church, Trinity, but in some ways Black churches in general, what role do you see them playing in this next phase of vaccinations and hopefully a nurturing back to a better… to not normal, but a better normal, a better way of being?

Rev. Otis Moss III: First thing I want to say, thank you, Eboo, for allowing me to be a part of this conversation with such incredible warriors who are doing amazing work in the faith community and organizing and just shining light in dark places. And you, who I have just such great respect for and the work that you have been doing over the years is such a blessing. At Trinity United Church of Christ, right on the south side of Chicago, we have witnessed the deep pain of this pandemic. Roughly about 90 or so funerals we could not do, because of this pandemic. We are one degree of separation within this congregation. Everyone knows someone who has COVID, had COVID, or has passed as a result of COVID. It became critical for us to educate the congregation about the challenges of this particular ailment and this particular disease. We had to let people know about, they need to get tested. We had to be able to communicate to people about all of the misinformation. I put it this way. I said, you would never go to Ray Ray, Pookie or Leroy if you want someone to do some surgery on you. Please, do not go to the barbershop or the salon to find out about information about COVID-19. I said it jokingly. But there was so much misinformation early on about this disease.

If you take COVID-19 and pair it with COVID 1619, the original American pandemic, you put those two together and you have a disaster and a tragedy. And that’s what we are witnessing. So, Black churches across the nation, I was just a part of a program yesterday, have been doing vaccination information, and also actually vaccination location. What we have found is when churches and trusted partners are partnering with public health officials, you have a higher level of people getting vaccinated. In Chicago, there has been a 70/30 flip. In other words, vaccination in Black communities, primarily the people getting vaccinated, are white. But yet when they get into the churches, it flipped 70-30, where 70% of the people getting vaccinated became African American and 30% other. Solely because of, one, misinformation, two, because of the digital divide and, three, in terms of how public health officials that are caught within the minutiae of bureaucracy end up passing on information. It becomes a community partnership. It’s not just vaccination. It’s not just education. But doing a full-service, holistic health. What does a healthy community look like? What does healthy policy look like? What does a healthy educational system look like? All of these are factors that affect life expectancy and the full health of an individual and a community. It’s important that we are connected to this type of engagement.

Eboo Patel: I appreciate that so much there. I think that there is going to be… this notion of COVID-19 1619. I think you have injected a new dimension into American discourse with that coinage. Thank you for that. That is so, so powerful. Otis, we’re going to be returning to this idea of the role that faith communities play in full service holistic health. One of the things I think many of us are aware of is that there is this potential to instrumentalize faith communities right now. Let’s get the Black churches to do vaccination education without recognition of the massively important role that Black churches and the faith communities have played in holistic health for many, many years and can play for years to come.

I think that’s a perfect sideway to the work of Dr. Kameelah Rashad. One of the first PowerPoints that I saw on the role of religious identity and vaccination was Dr. Rashad’s and it was passed on to me by our mutual friend, Jenan Mohajir. I don’t think you know that, Dr. Rashad, but eight weeks ago, I think before virtually anybody was thinking about this, you were on it, right? With your group, the National Black Muslim COVID Coalition. Tell us what you were seeing, you know, tell us what you were seeing about the role that religious identity played in attitudes towards the vaccination, the vaccine, and the role that religious leadership, like yourself, can play in building trust for it and facilitating vaccinations.

Kameelah Rashad: I have to echo, first the words of Reverend Otis in thanking you for really bringing this conversation to the fore. We are well into a second year of the pandemic. So, I want to extend my condolences, my prayers, just duas for strength, for mercy and grace for those who have lost members of their loved ones, family members to COVID-19. And also, for all of the other losses that we’ve all experienced as a result. It’s been a really, really, incredibly difficult year. In some ways we see the vaccine as a silver lining, one of those sorts of messages of hope. But we know that the work continues.

So, with the work I’ve been doing with the national Black Muslim COVID Coalition, it’s really designed to bring to the fore the idea of pairing religion, race, identity, and healing. Understanding the magnitude of this crisis for what we are going to have to deal with in the short-term and the long-term. Back in May of 2020, it’s hard to believe we’re in 2021. We launched a national survey of those who identified as Black or African American and were able to get almost a thousand responses in a really, really short period of time which let us know that people were really desiring a space to talk about their experiences. What we found was that those responders, those participants in our survey represented all faiths. The major Abrahamic faiths of course and one of our findings that I think is extremely important for this discussion is how people are coping. Coping with the loss. Coping with just the amount of, perhaps, despair that they are feeling. One of those ways of coping is meaning-focused coping. Understanding how faith, spirituality, connection to the divine, to the creator can offer an opportunity for us to think about what can we make? How can we transform this misfortune, this adversity, into insight, and understanding and wisdom?

For those who are using meaning-focused coping, in order to understand the vaccine and the role that vaccination and religious leaders can play in getting more people access to this vaccination, is that meaning-focused coping is sort of the wheelhouse of religious leaders, right? Being able to provide that context, that spiritual understanding, and to say, yes, Muslims believe, and we say that God does not place a burden on anyone greater than they can bear. Our religious leadership, our faith leadership can help us think about, what is the context of that burden? How this vaccination can help relieve that burden? There does not have to be a dichotomy between religion and science. I think the wonder that we find within the scientific world, for me, is manifestation of the majesty of God. So, when we have this as a potential solution to begin to help us think about how we can slow this devastation in our communities. I think our religious leaders really have an opportunity to provide, again, that context. To acknowledge and affirm the mistrust, the trauma that communities have experienced due to systemic racism in the healthcare system. Also, to say, now here is an opportunity, what can we do with each other and for each other in order to sustain our communities and the lives of our community members?

The last thing I will say is that another way that religious leaders can be incredibly significant is also talking about this idea of spiritual bypassing, right? And so, within kind of our usage as Muslims, we tend to say Mashallah, Subhanallah, Alhamdulillah, giving praise to God. There is also a way it’s used for people to kind of… if they are struggling and overwhelmed by just all of the unresolved emotional issues that the pandemic is bringing up to say, “Well, I will leave that in the hands of God.” Right? But we also know from our tradition is that our prophet has said, “trust in Allah, trust in God and tie your camel.” What are those things you can do within your control to protect your loved ones, to insure they are healthy, that they are able to connect and be with one another? All of that is within our power, given, really, the blessing of science and of vaccination. My brother is an engineer, he has been manufacturing vaccines for almost ten years, and so, when I see him, even within our sort of immediate family and community of loved ones, talk about what this means, it’s using, it’s pairing the spiritual and religious language and understanding with the benefit of science, which has always gone hand in hand with our understanding of ourselves and the world as Muslims. I’m really excited to see religious leaders to step into this role, to work hand in hand with our scientific community, with our healthcare professionals, in order, really to provide relief, understanding, context, and grace for those who are either confused, or afraid. That’s what we are seeing a lot of.

Eboo Patel: Thank you for that. [indiscernible] That’s so beautiful. Thank you, Kameelah. Because I’m a Muslim, I resonate with so much of the language that you use. So much of the spirituality is common, but the distinctive language of Islam, when you say there is no dichotomy between religion and science, I think of the term “ayah,” which is commonly defined as a verse of the Quran, but it also means a sign, which is to say a sign of the world, so the Quran says over and over again, it points to the different parts of nature. Birds and trees and lakes and rivers. It says, these are signs of God. Right? So, there is this sense that it is effectively a Quranic command to explore the signs of God through his creation and to be in a way a fellow creator as in someone who develops cures. You seek knowledge into China, and you seek to be a mercy upon all the world. We are in a situation right now where faith leaders and scientists really are on the same page. It’s not always the case. Right now, we are on the same page. It’s beautiful to hear the story about your brother who is an engineer and the work he has done in saving lives through producing vaccines. Thank you for sharing that.

If I could switch to my friend and mentor, Jim Wallis, who I’ve known since 1995. I showed up as a college sophomore on his porch looking to have a conversation with somebody whose work had inspired me as a college student to really take the path of faith and social action. Every time you turn around Jim is leading some kind of national effort to improve the lives, particularly of those who have been marginalized by COVID 1619 or by other forms of discrimination. He is doing it again in his work with Faiths4Vaccine. Jim, it’s great to see you, friend. Congratulations for 50 years at Sojourners. Congratulations for your next steps at Georgetown, in between you have found yourself doing God’s work and the nation’s work with the Faiths4Vaccine group. Could you tell us a little about that?

You’re muted friend.

Rev. Jim Wallis: Dr. Rashad beautifully framed faith and science. That’s the foundation for this whole conversation. How do we reframe faith and science? So, thank you for that. Otis Moss is one of my favorite pastors on the planet, let me say that. I love to tag team with Otis on anything that we can do. Rabbi Hirschfield, I have heard great things about you, so I am wonderfully glad to be with you. Eboo, I’m glad you started theologically and not just politically, or practically, because when you talk about Shalom, meaning wholeness, it means the restoration of relationships, which is inclusive of justice. There is no healing without justice. That is what Dr. Moss is saying to us today.

This pandemic has been, to use this theological term, this pandemic has been revelatory. Revelatory. It has revealed and documented and verified the inequities in this society. And so, we’ve been saying these things for a long time, but this pandemic has verified everything that we have ever said, that the racial, economic inequities in this country have been revealed by this pandemic and how it has impacted people of color in very disproportionate, powerful, dramatic ways. When Otis Moss talks about how many people in his congregation have been touched. 90 funerals that you couldn’t have in the same way that you normally would. This is tremendous trauma and suffering.

So, this coalition that you mentioned that I’ve been able to be a part of, started when I got a call from Dr. Mohamed Elsanousi who was once the youth director of ISNA, the North Islamic Association. We worked together before. Here’s he calling, “I got the Islamic medical society ready to do vaccinations at our mosques. Can we do that?” These are doctors, nurses, as Kameelah knows well, and he said, “yeah, but let’s make it interfaith.” So, he gave me a call. And I said to him then and I will say it again now, “When God speaks to one of us about something like this, it’s likely that God is speaking to other people, too.” Not just us. So, this coalition has come together. Still the leadership point person is this young, wonderful, young Islamic leader named Mohamed Elsanousi, and his team. But it now includes the National Association of Evangelicals, the National Council of Churches, the Catholic Hospital Association, [indiscernible] amazing churches all over the country. A lot of local AME church leaders in lots of places.

It’s become a large coalition offering three things. One, as Reverend Otis was saying, clergy are already offering houses of worship as sites for vaccinations. It was happening before this coalition started. Many are now, sort of, projects of teaching us all this, sites. It does turn things around. Like the 70/30 change that Dr. Moss talked about. Because these are trusted locations. Trusted locations with people, clergy who have trusted vocations. So, it’s a site that’s trusted. It’s the messaging and messengers who are trusted. And can reach out to people. And finally, it’s at the core of what this administration is really trying to commit themselves to, which I admire, and they are falling short which they know, which is the equitable distribution of these vaccines around the country. Right here in D.C. Washington, D.C. Ward 8, Black ward, has not been vaccinated the way it should have been. Where ward 3 has been. Right? So, when you turn these vaccinations around, equity and for Shalom, Eboo, equity is core to what Shalom has to mean.

We have been in conversation, even yesterday with the White House and what they are saying is, “it’s not whether faith communities should be involved, it’s how.” How do we do this? We are not saying send us your vaccines and we’ll put them in our church refrigerators and administer them with our volunteers. We’re saying “no, we can create the spaces, the Parish halls, the parking lots, we can do the message. We can get people to come, volunteers, parking attendants. We can provide that, but we need people to provide the wherewithal, the vaccination, the logistics to make it happen.” We are partnering with, they want to partner with us, at the federal and state and local level. That’s been sometimes difficult, as Reverend Moss knows with some of our pilot projects, that reached with local health officials, and they weren’t always quick and easy to respond. We are changing that. The message will be yes. Collaborate with, work with houses of worship as vaccine sites. But let’s choose ones that would help us with our equitable distribution of vaccines.

And so, I think that messengers’ messaging with equity at the core is now, I think they’re talking about co-creating a plan where this could be help and assisted and, Eboo, you brought in a healthcare operation Oak Street from Chicago and when I got a call from Dr. Choucair, who is the chief White House vaccination director of this whole thing, he says, “Oh, I was Chicago health commissioner once, I know Mike, I know all those guys. Sure, we would love to work with them.” Once you start to connect, all of these connections begin to fall into place. We are not asking the government to treat us as a constituency. Please take care of us, too. No. We’re saying, “we are making offerings. We are offering our assets, our networks, our clergy, our sites.” We are offering that, to vaccinate this country, but not just to heal from this pandemic. But to transform, as you said Eboo, our healthcare systems. Our healthcare systems have been infected by systemic racism. That has to be healed. How do we learn from this going forward of how to do holistic healthcare in this country going forward? We have to restore. We have to repair. We have to fix that. We can’t just heal from this pandemic and act like everything is okay. Everything isn’t okay. The pandemic has revealed that. How do we use this as an example to transform our healthcare system? So, in fact, they are inclusive of all of us. That’s what we can do here. Not just help in the immediate crisis but take this thing forward to a much deeper level. Part of our vocation.

Eboo Patel: Building back better is not just a government plan, it’s a theological imperative. And to have theology at the center of that and, look, part of the beauty of running an organization called Interfaith Youth Core, or IFYC, is we proudly lead with the positive dimensions of faith communities, right? The community building dimensions of faith communities, and thank you hovering a bit, Jim, on Shalom, and highlighting that it’s not principally a quality of an individual. It’s principally the quality of a community.

I’m glad we’re turning to a Rabbi next because, of course, the term Shalom comes from Judaism, the rabbinic traditions. Brad and I have known each other for 12 or 15 years, I was joking with him, the last time I saw him he had a ponytail. He had recently completed a terrific new book called, “You Don’t Have to Be Wrong for Me to Be Right.” And he offered at a presentation that I saw, a metaphor that I still use regularly which is that religion is powerful. It’s like a fire. It can heat your dinner, or it can burn down your house. I think I made reference to that, with the proper citation, Brad, just yesterday. So, thank you for… every single one of you has offered a little line that I will borrow and use, like a D.J., in my future performances and tellings with proper citations. Brad, tell us, as a Rabbi, what are you seeing in Jewish communities? And Otis and Jim and Kameelah have each offered wisdom from their particular traditions. What is the particular wisdom from Judaism that we can learn from when it comes to the intersection of faith and science, at the intersection of this vaccine, but, really, at the intersection of the theological focus in building back better?

Rabbi Brad Hirschfield: Thank you for the brilliant questions. Before I do anything else, this reminds me why, selfishly, I participate in these panels. Because my education continues. And I am both grateful and humbled by all of you, by your work in the world, and your brilliance. So, I want to thank you publicly as one of your students. Because how often in this polarized world does a Rabbi get to thank two Muslims, two Christians, not just for being good, ethical, caring, brilliant people, but actually for being my spiritual and intellectual teachers? I don’t say it lightly. And Eboo, despite your modesty, I want to be very clear, you are every bit as much the leader of a faith-based congregation as any of us. Whether or not we have the rubrics or the categories that make it possible for hundreds of millions of people to embrace that, that’s a sociological issue. It is not an issue, at least for me in my soul, in my heart, in my mind, of the reality of what you and IFYC have done and continue to do. So, I’m very grateful to all of you.

I want to be clear, this is relatively easy if I look at the Jewish community, because Jews overwhelmingly embrace science and vaccination and the cause of equity of access to vaccines. In fact, one could make the claim that Jews embrace science and vaccine and equity more than they embrace God and religion, but that’s a separate conversation for another time. It beguiles some religious leaders and Dr. Rashad mentioned one of the ways to approach it, I think, and I believe, that it is deeply in the tradition, that it’s an artificial divide. It’s a false dichotomy, to imagine that people can embrace science and equity and the healing of people’s bodies is somehow a separable category from God and faith and religion. So, in that sense this is pretty easy.

Of course, there are exceptions in the Jewish community as there are in every community. Most notably, if one looks to the press, it’s going to be in segments of the ultra-Orthodox or in Hebrew Haredi, which, although it doesn’t work as well in English, literally means “to be awestruck or to be a quaker.” So, it turns out there are two kinds of Quakers. There’s the kind of Quakers most Americans know and there are the Quakers, although it’s a term they wouldn’t use within ultra-Orthodox Jews, men in black hats and women in wigs. Even there, the issue really is not resistance to vaccines. The issue is not resistance to science. The issue is much more a matter of trust in authorities and the institutions that are at the forefront of sending out those vaccines into the world. I think that is really, really important because as much as we can create theological framings that we and here the “we,” is those of us on this seminar, who I’m guessing largely agree. There have been so many points of agreement between all of us. We could easy, well it ought to be easy. At which point I would say, “well, it depends which ‘we.’” Because for the “we,” whichever religious community it is that doesn’t trust the institutions and doesn’t trust the agencies and the authorities that have sent vaccine and vaccination out into the world.

While it’s true that a theological framing will help, my experience is, with the best of intentions, and I’m including myself, we all tend to frame things in theologies that work for us, share them with others, and then say, “now you see it?” Of course, the answer is no. And not because they are stupid or bad, but because their theological premises are not ours. One of the real challenges is how do you combine a massive dose of intellectual and theological humility with an equally massive dose of passionate engagement and activism? Because all the theological framings in the world won’t help if they are not the other person’s theology. If I’m really honest, there is no theology, however artful I can come up with, and I won’t speak for anyone else, that doesn’t have an equally good one that is the polar opposite. Once I accept that, I know there is no master narrative theologically that will suddenly convince other people, because I don’t think the issue is fundamentally theological. It is, as I said fundamentally, no pun intended, a matter of trust. And trust-building is very different than policy advocacy. Even though I deem them both to be sacred categories. Advocating for better policy that reflects what I believe to be, what I believe, that’s all I can say, God’s will for the world as I best understand it, I think is holy work. But I also accept that that’s often diametrically opposed to trust building, because trust building, whether it’s the work of [indiscernible] or even Pete Buttigieg’s book, which shares the name, “Trust,” works best when it’s independent of advocacy for a particular conclusion. It works best when we are willing to go to those with whom we disagree most and show up for each other. On the terms of the other. That doesn’t mean everyone has to do it with everybody. Nobody can. But it means we have to be very careful I think about the difference between advocating for the policies which we deem sacred and doing the trust-building, which is typically best done, and it’s hard, when it’s disconnected from advocacy. When it is about pure presence and relationality. Even when that means building relationships with people we may think are completely crazy, or worse. But there is no shortcut to building trust. The interesting thing is, ‘cause you did get the quote right, faith like a fire which can cook our meals or burn down our homes.

The second half is, of course, that the issue isn’t the fire, the issue is those who wield it. We have to decide how do we want to use faith. Do we want to use it to show people the light? Or do we want to use it to give ourselves the courage to build trust with people who may never see the light as we see it? I can’t decide which is right. But I know those two are different. We have got to be mindful. Especially because I know of no form of community or personal experience that can build trust or undermine trust like religion. People can gather in communities of faith and experience the capacity of trust people when they know intellectually makes no sense to trust those people. And they can also, and yet dare to do it. To trust that which isn’t trustable because that’s what faith allows us to do. Or we can gather in religious community and it can affirm and confirm why we don’t trust those people, whoever those people are. We know that right now in this country, faith communities and houses of worship are being used in both ways. It’s not a matter of right versus left or Jewish or Christian or Muslim. We can go to progressive communities, that have mobilized the word God to teach profound distrust of conservatives and certainly in the reverse, at least as much if not more. And it’s not the domain of any one particular tradition. So, I think, really, the spiritual work here, for me, is to appreciate the work of trust-building ahead of policy advocacy. If, ironically, I want to see policies change. Because short of coercion, which I’m not a big fan of, the only tool left is to build relationships and trust beyond current boundaries. That is not informational. And then I’m going to will shut up, I promise. Especially in a moment as tempting as it is, well, just give them the right information! Truth is, I would suggest that the actual challenge we live in at this moment is not that we lack information, it’s that we have too much information. For the first time maybe in 10,000 years of human history. The fundamental challenge is not gaining access to information, it’s developing the wisdom to know how to sift through it. And to do exactly what you said, Eboo. And what our current president ran on the promise of building back better, which in my view is not a terrible way to summarize any of the traditions we follow. To build back better and do it with both the passion to advocate for what we believe, and the humility to appreciate the multiple understandings of better, which would allow to us build trust where currently there is nothing but mistrust.

Eboo Patel: Thanks, Brad. With your focus on trust, I’m reminded that the Prophet Muhammad may the peace and blessings of God be upon him. That the term that people would call him even before he was publicly announced as God’s prophet was Al-Amin, which means “the trustworthy,” right? Part of what that indicates is there is a, beyond the tribal mentality there, there is a sense that this person’s dignity and sense of decency and generosity, it is widely recognized as trustworthy. So, thank you for lifting that up as a sacred value. I think one of the interesting spiritual challenges of our time is, what does it look like to be trusted by people with whom you might disagree and who may disagree with you? You may even vote different ways. You might have fundamental disagreements, but you look them in the eye, and you say, “this is good for you,” and they believe you because they have a deep sense of your dignity. I think that’s a powerful reminder of an opportunity. I want to take that ethic into this next big question.

I want to direct this specifically to Otis, because he’s going to have to leave us a little early. Otis, I am deeply struck by Jim’s revelation, Black churches are trusted locations with trusted vocations. Your data point that when Black churches serve as locations of vaccinations, it’s not white folks on the north side of Chicago making their way to the south side for vaccines. Its Black folks getting the vaccine at a site that they trust. And it’s so interesting that the same individual who sits in a doctor’s office as a patient might not listen to that doctor’s advice. But when they sit in your pews, Otis, as a congregant, they trust you. And they will, in effect, do the same act in a different frame. So, here is my big question. There is a great article about you recently in the Chicago Sun Times about the role that Trinity has played in the physical and spiritual wellness of its congregants, around nutrition, around heart disease, etc. Let’s say, God-willing, that we vaccinate every American. Between now and June. And the emergency is done. If you had a meeting with President Biden and Vice President Harris and they were to say to you, “Otis, what’s the role that your church and faith communities in general…” I’m going to ask everybody some version of this, right? “What is the role that your church and faith communities in general can play in health outcomes? Tell us what you can do. You can’t perform surgery, you know, on the pulpit. But tell us what you can do and what are the resources that you would need to do that?” What would you say?

Rev. Otis Moss III: That’s a great question, Eboo. I would say that faith communities have to be an anchor for holistic community development. And let me explain that. I will give you a very small example. There’re groups of churches in Chicago, that made decisions to do gardens. As a result of doing gardens, something happened. One, intergenerational communication. Two, it reduced the level of violence in communities because you built relationships with individuals. Please remember, we need to begin to think through, when we talk about public safety — it should be public health. We don’t need to frame as policing. That’s a health issue.

The next piece is that within churches, especially your Pentecostal, your small church communities, when the elder in the church, I’m not talking about the pastor, I’m talking about there is usually an elder woman who runs the church, let me just say that. The elder makes particular decisions and says, for example, “we are going to now purchase from this local farmer, on this local farmer’s market.” All of a sudden something changes. We had an experience when we started our farmers’ market where people did not, some people didn’t, they were looking at squash and they were like, “well, yeah, that’s nice, but what do you do with it? I’m used to packaged food.” So, you have this anchor that can be in the heart of the community, seeking the community’s heart, that can allow people to imagine differently. To use their imagination to see holistic health differently. From what I eat to what I grow, to viewing what is policing as public health.

If I view it from public health, then I raise different questions when it’s public health. When I look at education as public health, I raise different questions. When I see incarceration as a health issue and not as this issue of retribution, but of redemption and restoration, it changes the outcomes. The faith community can give new language to the civic community. Language of restoration, redemption, of love, of empowerment, of community. Language that politicians are very skittish about using. When was the last time you heard about a politician saying, “forgive me,” unless they did something very bad?

Eboo Patel: And then only sometimes.

Rev. Otis Moss III: Then only sometimes. But we have a new language that we have to put in the public’s sphere. All of the faith traditions bring this language to the table of how do we become fully human?

Eboo Patel: Otis, what strikes me about this, I think what you are talking about is a fresh and new chapter in a longstanding American story. Because so much of the language that is actually used in the civic community is faith language. We just forgot it is faith language. Beloved community. Cathedral of humanity. Almost chosen people. Better angels of our nature. City on a hill. This is all faith language. It is scriptural language. Muslims will often refer to America as “A new Medina,” at its best, the city that welcomed the prophet and his companions after they were hounded out of Mecca. You didn’t say, “my church can run this one more program.” You centered a faith community within a polity, and you talked about its relationship with everything from public safety to nutrition to community economics. Buying from that local farmer is not only how food is grown and what people eat, it’s also how economics happens, right? So, this kind of community notion of Shalom can easily have a faith community or faith communities at the center.

I want to turn for a minute to Dr. Rashad and ask, you not only have launched the Black Muslim COVID coalition, but you ran the Muslim Wellness Foundation for a long time. None of the people, including and especially you, Kameelah, are new to this. This not like COVID happened and all of a sudden you got interested in health. It’s much more like you have been paying attention to the intersection of religion and health for a long time and we are finally paying attention to you, right? What promise do you think this moment has for interfaith cooperation on health, on the kind of expansive notion of health and wellness and Shalom, that Otis mentioned?

Kameelah Rashad: I think this is such a tremendous opportunity, because what we’re going to see is that, while this is a health crisis, it’s a crisis of all of those inequities being revealed to a greater number of people. This is also in some ways an existential crisis. That people are asking themselves about belonging. About mutual aid. About who do I belong to when I experience this kind of suffering and despair? In these moments people are turning, right, kind of returning to that which grounded them for a long period of time, and perhaps at different points in time.

But I think what it offers us now is an opportunity to widen that net and to think about how we integrate religion and spirituality and health, such that it’s not just, you know, “if you’re going to pray go over there, and if you’re going to see the doctor, you go here.” Ideally, folks should be able to access this menu of health in one location. And so, what does that mean? If we are talking about your spiritual nourishment, your physical nourishment, your emotional nourishment, how profound would it be for individuals to see that, one, all of the professionals are on the same page? We are supporting one another. We’re complementing one another’s work. And so, if someone is coming to me with a psychological ailment, I’m going to ask them about their connection to the creator or not. How do they see the world and their relationship to humanity? I’m going to ask them about, you know, are you getting enough exercise? What does your diet look like? And so, once we connect mind-body-spirit we allow for others to give themselves permission to say that I should not compartmentalize my own life, right, when the world is expanding opportunities for me to be fully integrated and to be fully whole.

So, what I think this offers us now is when we’re talking about government, we’re talking about politics and civic engagement, it’s usually crisis points where we see a resurgence and recognition of the role of faith and what I really want to see is that once whatever this moment becomes next, that we don’t wait for another crisis to demonstrate how integral the religious and faith communities are and how we understand our lives in this country. And so, as a psychologist, I talk about post-traumatic growth, right? This period of time, this COVID-19 has been incredibly traumatic. I want us to use that language because of the number of transitions and losses that we’ve experienced. But there is also post-traumatic growth. How do we gain wisdom and insight and a new way of being from this experience we’ve all shared? And that includes pulling in all of those individuals, leaders to sit down at the table and to say, “Honestly, I need you. For my work to be effective and to be meaningful, I need to sit hand in hand with you. I need to appreciate your work. I need to appreciate the values and perspectives that you bring. We can come to some shared understanding because all of our roles, essentially, is to serve.” Once we can do that together, I think that we are more powerful. We are absolutely just, it opens up, again, those possibilities for this work to be sustainable over a long term. Not just this time. But so that, when we are looking back 10 years, 20 years, we can say that this was a turning point.

Eboo Patel: I have to say, Kameelah, my terrific colleagues at IFYC, part of what some of them are doing are listening very closely for powerful nuggets that can be shared and in every other line you say is one of those nuggets. So, I’m just going to name a couple of them: How do we transform this misfortune into insight? How do we practice meaning-focused coping and how do we engage in post-traumatic growth? That is really powerful. I can see, Otis is like, “I’m done with my next sermon.” Thank you so much for that beautiful wisdom. And it’s so clear that everybody on this panel has been thinking about this for years, right? And like so many other things, it’s, you prepared for the crisis before the crisis hit. And we are now preparing, not only to engage and hopefully solve the crisis, but to build in a way that makes crises like these a lot less traumatic and challenging in the future.

So, I’m going to turn slightly different questions to Jim and Brad. We’ve got about five minutes here. So, Jim, in a couple of minutes, you actually do speak with senior people in the administration on a regular basis. You’ve done it for years and years and years you and years. So, this isn’t a hypothetical for you, Jim. When you speak with Susan Rice, or Vice President Harris, or President Biden and they say to you in August, “Hey, Jim, that faith coalition that you played a central role in, that Brad Hirschfield and Otis Moss and Kameelah Rashad were all a part of, how does that faith coalition play a role in the health and wellness strategy for America over the next 100 years?” It’s a version of the question I asked to Kameelah and to Otis. I would love to hear your answer to President Biden about that.

Rev. Jim Wallis: This conversation reminds me of the Chinese symbol for crisis is the two symbols in Chinese for danger and opportunity. People turn to us in a crisis because we can respond. Practically, they are trying to outrun a race against variants of this virus. That’s what makes this not theoretical. Right now, we have to vaccinate enough people before the variants outrun the virus, that’s very practical. When Rabbi talked about the trust, young people don’t walk by our congregations asking, “I wonder what they believe in there?” They are asking, “what are they doing? What are they doing?” In response to a crisis, we do what we do, then they say, “why do you do what you do?” “Well, let me tell you what we believe.” That’s how what we do is the first response, and then we say what we believe.

Reverend Moss says a test of faith is you might also say the common good. Human flourishing. Community development. In fact, if we respond in a crisis in ways even the White House says, “that’s really helpful to what we are trying to do,” then we have a real voice in what’s next. What’s next? What’s next to talk about human flourishing and equitable medical systems that health is, in fact, healing means justice. It means all of the things, it means there are people, as Reverend Moss knows, in the Black Lives’ movement looking at churches and saying, “Well, we are unchurched. We’ve been kind of unchurched. We are not against all of this.” But I remember a conversation with Ferguson leaders and Reverend Moss where they said, “We want you to help us. We want to help you. But what risks are we willing to take?” And Reverend Moss jumped all over that and said, “that’s indeed the question.” What risks are we willing to take for the sake of what we believe? If we believe these things, a young generation looking to us for the courage to act on the things we say we believe. That changes what we do and it’s transforming, as the Sun Times article, which I haven’t read yet, which I will read, what are churches doing on the south side which creates trust? And then the authority for saying, in answer to your question, Susan Rice, what’s next? Here are some examples we have of what’s next. We’re not saying what we believe, we have done this, we like what we’ve done. Now we are saying we want to have a voice in what you all do next. And I think, we’re faith leaders have supported this big bill. It’s being voted on today. A big bill. That is in fact delivering relief from suffering and economic distress. They are already saying now, “what’s next?” Because what’s next is always the question we have to ask them and be a part of.

Eboo Patel: Yeah, Jim I have to say I remember in our time together on President Obama’s faith council, you would talk about completing the war on poverty from the 1960s. Completing that great society transformation. And you would talk about bills like this, and it happened two administrations later. But we’re about to see, perhaps, the greatest poverty fighting bill since the 1960s pass. There’s– your fingerprints are on that and your blessings as well. So, I was proud to be in the White House when you were whispering that in President Obama’s ear and it took a couple of presidents, but here we are.

Brad, take us out, friend. I’m serious, all right, we got two minutes left. All religions are communities of memory. Judaism in particular is a tradition of memory. What story do we want our grandchildren telling of us in our role in this crisis and our role in a new social architecture? What story do we want them telling of us?

Rabbi Brad Hirschfield: So, this is all just Moses channeling God. Behold today I set before you life and death. Choose life. And I use that scripture particularly because there’re real battles we’re going to have along religious lines about what it means to choose life. I don’t choose that accidentally. But if people actually could begin to appreciate about each other that even when we are not aiming for the same end result, we are in the same game. And it is a game in which the faiths we follow are not ends in themselves. They are means. To the kind of human flourishing, the kind of wholeness, the Shalom-ness, the Salaam-ness that we’ve talked about from the very beginning.

For me, it’s very simple. The fastest glowing religious group in this country are the “nones.” That’s not Catholic religious women. It’s “N-O-N-E-S.” But contrary to the sociologists who would tell us that means they want nothing from religion, I couldn’t think they are more wrong. For me, the nones are the people that, when presented with those little boxes, are checking “none of the above.” The contents of my soul, of my aspirations as a human being are bigger than any one box. Here is the irony. If we, ‘cause my message is to us, it’s never to them. It’s got to be, we have the greatest control over ourselves. But I think that Jim is completely right. Imagine if the religious leaders and religious communities had the courage to say, “We are not in the business of being in this business. We are in the business of building community. To serve humanity.” And our litmus test will be every time you leave our community, you leave it a little more understanding of others, a little more hope in the future. And a little more sense that you are as beautiful as you would like to believe, because whether you believe in God or not, we can affirm that story that we are all created in the image of God. Whether it’s a God we believe in or a God we don’t, I don’t care, I believe in that story and I also believe in God.

More than fighting about theology, I want to fight for that story. And simply ask every day when I wake up, and every day when I go to bed. Do I feel a little more in the image of that God? And did I do anything to contribute to even one more person feeling that they, too, are a little bit in the image of that God? We do that, I can’t tell you exactly what the future will bring. But I know our great-great-grandchildren will look back on this tragedy and they’ll say that we, their great-great-grandparents, we made the most of it given what couldn’t be changed. That feels like a pretty big blessing for me.

Eboo Patel: That’s what it means to be a witness, that’s what it means to be a mercy upon the worlds, that’s what it means to be the light of Jesus on earth. Whatever it is, whatever your tradition is, thank you for the inspiration. Thank you to everybody who was a part of this today. More resources for those interested at IFYC.org and to all Jazak Allah Khair, may God give you goodness. Thank you to the panelists.