Stanford’s 50 Year Struggle for Racial Justice

July 8, 2020

On April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr., was shot in Memphis and America exploded in flames of grief and rage. Four days later, on the other side of the country, Stanford University Provost, Richard Lyman, convened a convocation on the perils of White Racism at the Memorial Auditorium on Palo Alto campus – an event that featured an all-white panel and was attended by a majority white audience of 1700 campus community members.

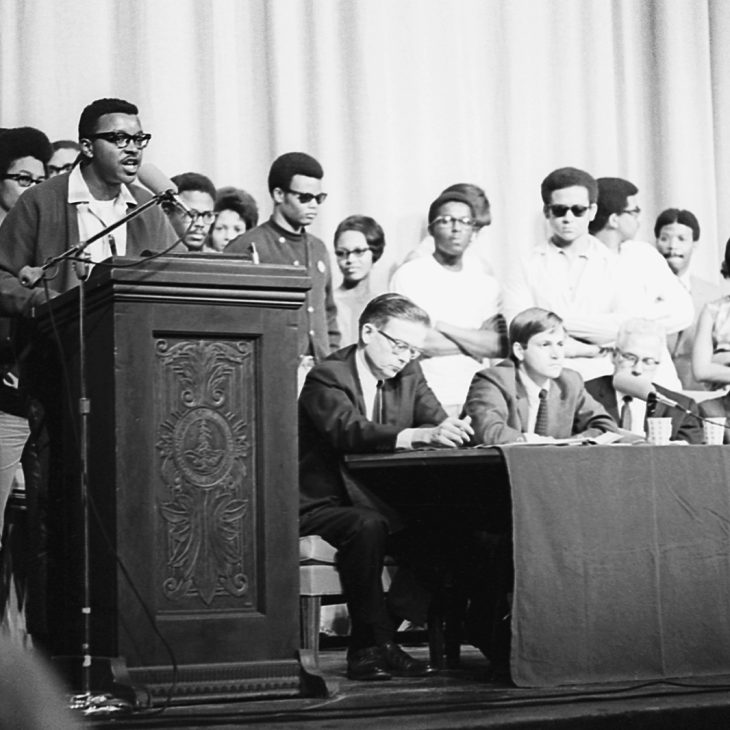

As Lyman was speaking, a group of 70 members of the Black Student Union (BSU) and local community members marched into the auditorium and ascended the stage, taking the mic from the provost mid-speech and shouting into it, “Put your money and action where your mouth is!” — giving the historic moment its name, ‘Take Back the Mic.’

Frank Omowale Satterwhite, a doctoral candidate in the School of Education, then read aloud a list of demands to a stunned audience: including boosting African American admissions, curriculum, hiring, and broader representation at Stanford.

As the group walked out of the auditorium the audience burst into a standing ovation. White students rallied together to form groups and sign petitions in support of the BSU. Lyman and Stanford President, Wallace Sterling, engaged in a three-day conversation and pledged to double Stanford’s Black enrollment – then about 1 percent of the student body – and to launch the first African and African American Studies program at a private university in the United States. A year later, in 1970, Stanford inaugurated the Black Community Services Center, which has been supporting Black students on campus ever since.

“Our Black House has been on campus for 50 years now and it came as a result of that powerful act of student activism,” says Dr. Rosalind Conerly, associate dean of students and director of the Black Community Services Center, which is affectionately known as the Black House at Stanford. “Back then our students did a lot of community organizing and worked with other Black students and groups around campus – our center’s history is rooted in the concept of unity. Fast forward to today and we are still doing a lot of advocacy work, but we are also supporting students through their identity formation, as well as intellectual development in and outside the classroom.”

50 years after ‘Take Back the Mic’, Black students, faculty, staff, and other community members marched on Stanford’s campus grounds again, as part of the national protests following the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and other Black people at the hands of police violence. Their demands for racial justice on campus echoed the words of their predecessors: boost African American student admissions (only 4.08% current students are Black or African American), hire more African American faculty members (only 2% of the faculty on campus are Black or African American), and create more robust academic opportunities by establishing an independent African and African American Studies department (the program was established in 1969, but it’s not a department of its own).

Stanford’s administration responded to the moment by hosting a Campus Community Vigil for Black Lives, curated by the Community Services Center, Counseling and Psychological Services, the Office for Religious Life, and Ujamaa House — an African American themed dormitory whose intellectual focus spans the entire African diaspora.

“What Stanford did well was to recognize that if we are going to have a vigil for Black lives, we need to center Black voices and it needs to be represented and executed by Black people,” says Dr. LaWanda Hill, staff psychologist on campus. “Typically, the administration’s response doesn’t necessarily stick to the voice of the people they’re trying to honor, hence why incidents like ‘Take Back the Mic’ happened 50 years ago – it was the people’s effort to make the administration listen to them. I think it should be the first piece while responding to a moment like this across the globe – because when you don’t listen to our voices or consult us before you build spaces for us, you do more harm.”

In addition to the vigil, Stanford’s Student Affairs office published a Black Lives Matter webpage that offers opportunities for people to advocate and donate to causes, while also listing resources for people to educate themselves and find ways to take care of themselves and other community members.

Dr. Conerly commented that while the initial response from the wider campus administration has been respectful and impressive, she hopes to see more movement around actively identifying systemic racism and white supremacy on campus, and offering Black community members the spaces to be more involved in decision making.

“Anti-blackness is cancer,” says Dr. Conerly. “And to treat cancer you will need to look at the structures, the policies, the lack of representation and diversity, the unconscious bias that perpetuate white supremacy at the expense of other people. The website, the vigil, the brave spaces are the bare minimum the campus can do, but that’s only like offering cough syrup for cough symptoms, but you are dealing with something much larger here. You need to be looking deeper. That’s the move I’d like to see – and if that move happens, that’s when we will know that this momentum is actually moving us forward.”

Other staff members also expressed the need for more internal change within the campus.

“I’ve been here a really long time and I know the lay of the land, I know all the buttons, the bones, the trauma that I’ve been through for being Black,” says Jan Barker Alexander, assistant vice provost of Student Affairs, Centers for Equity, Community, and Leadership.

She adds, “There are two different paths from this; there are cynicism and skepticism, and then there’s hope. As a woman of faith, my faith is important to me and it teaches me to be hopeful about the future; but there’s also all the lived experiences, the history, that tells me that despite all the marches and the support – look how long it took us to get voting rights, and look, still, where we are today. Some people will be pacified by small spaces, but us who have been around longer, we want to keep pushing for bigger, more structural change within the institution.”

Despite the air of uncertainty and skepticism, the staff members also shared moments of hope that were brought around by the campus’ response to the moment.

“Our inboxes are on fire,” says Alexander. “We are continuously receiving so many messages of hope and support. One person, she graduated from Stanford Class of ‘92, and now she works here, and her father’s a professor here too. She wrote to us about the vigil and said, “I never thought I’d see anything like this on campus.”

She adds, “And that means so much to us that a lot of people around us don’t seem to understand – that this is not just a moment for us, this movement, this is what we’ve been dealing with our whole life. We are not brave or courageous just today, but Black people, especially Black women, have had to be brave all their life.”

Share

Related Articles

American Civic Life

American Civic Life

The Interfaith Legacy of Muhammad Ali: “The Wise Man Changes”

American Civic Life

Is This a Time for Bridgebuilding? 5 Leaders in Conversation