I’m Grateful the “Death Card Does Not Mean Death”

January 13, 2021

It took awhile for quarantine to hit me.

I tend to pride myself on how well I cope with stress. Everyone was swirling with anxiety around me, but for the most part, I was still fortunate enough to be getting a paycheck, and able to teach my students from home. It was annoying of course, but I appreciated the reprieve from the incessant decision-making of classroom teaching. When the news got overwhelming, I turned it off. When I felt restless, I meditated. I prayed. I exercised. I journaled. I Netflixed. I played video games.

I thought I was doing pretty good.

It took a jog on a chilly summer morning for me to realize I wasn’t.

Sprawling and wooded, Washington Park, is an island of fresh air surrounded by an ocean of concrete on the South Side of Chicago. I went early, since Covid had led to the park getting more crowded than usual by the middle of the day.

I was jogging on the paved road for no more than two minutes when I spotted it, a single lone white pick up truck parked off in the distance. A hooded figure could be seen near the rear, dressed darkly, with a leashed pit bull near him. I stopped and squinted to see a bit further. My heart beat a little faster. This would’ve otherwise been an ignorable occurrence, but just a few yards ahead of both of us, on the paved out trail, a marker “Start here,” lie written in the concrete, it was meant to signal the beginning of the 2.23 mile run that had taken place a few days prior, for Ahmaud Arbery, one of many commemorative runs that took place all over the country.

Ahmaud, an unarmed Black man, as the phrase goes, had been shot jogging by two white supremacists who had pulled up in a pick up truck.

This was the moment when I realized the effect that all the Black deaths of the summer was having on me. For a split second, flashbacks to the Arbery case stopped me. I had no idea who was in that pickup truck. I felt stunningly vulnerable in the realization that he was doing exactly what I was doing. And just like him, all it would’ve taken is some lone white supremacist, aimless and resentful, to take my life.

Jumpiness is the simple word for it. What I don’t have a word for is the source of the jumpiness. What I don’t have words for, and what it frustrates me that even liberal White America can’t understand, is the sudden awareness that you could die from a sheer ordinary moment, in a country that places no value on your own life.

After a breath I kept going. And I soon got close enough to realize that the figure was a Black man, and relief swept over me. I looked down at the marker once I passed it, now breathing from not only jogging, but from trying to put the moment behind me, now curious to see how long I could jog 2.23 miles before running out of breath.

I’ve been thinking about my death more than ever lately.

Not suicidally, but quite frankly, it’s eventuality. I wish the world could understand what it means to be Black during the middle of a pandemic. Like pulling petals off a flower to see whether someone “loves you” or “loves you not,” 2020 repeatedly showed Black people the scope of possibility for their death. Police. Covid. Trump. Take your pick.

“The Death card doesn’t mean ‘death’.”

When doing readings for others new to tarot, I have to offer a series of disclaimers to combat media portrayals. The aforementioned phrase is one of the first to come out of my mouth. People often come to readings with a sense of urgency fueled by superstition, and to see a card like this easily raises a few eyebrows.

It makes sense, death is the only guarantee in our lives. And people often turn to divination for prediction, so of course, the one thing everyone is afraid of is ironically the only thing guaranteed.

But the death card doesn’t mean death.

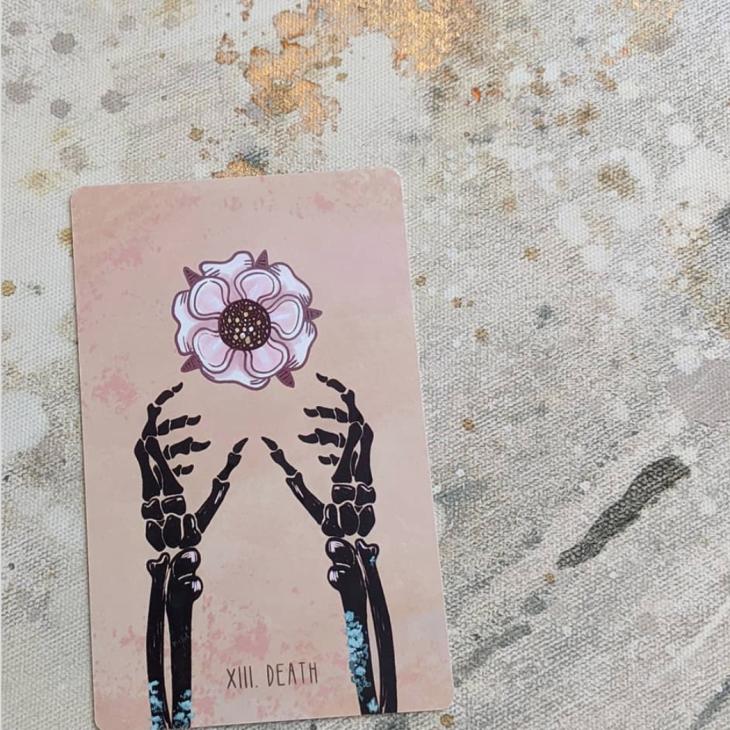

One of my favorite depictions of the Death card in the Tarot is by a woman named Carrie Mallon. It captures the essential essence of the Death card, it shows two skeletal hands, clearly bewildered and tired, reaching out for a small pink flower, centered in the middle of the card. Here Death actually becomes a sort of revival. A subtle, gentle reach for hope. It’s not a naive hope, you get the sense that the figure in the card bears no illusions about what they’ve been through, they are dead after all, but rather in their death they still find that flower worth reaching out to.

This image gets at the true meaning of the Death card, which in actuality, is really about rebirth. An Ego death. Transformation. When it appears, there’s usually some outdated part of us that is falling away, whether we’ve been ready for it or not.

What’s powerful about this card, is that it’s one of the few times we actually get to engage with death in a context that signals us towards renewal rather than anything else. It’s one of the few times, when “death” doesn’t mean “death.”

Blackness and death is so synonymous with one another in the United States, that I take that reality for granted. The beauty, is that the other side of that reality, what people called Black Excellence, Black Girl Magic, Black Boy Joy, is the innovation, charm, and boundlessness Black people have been able to create when, as Lucille Clifton writes “everyday something has tried to kill me / and has failed.”

Meditation, prayer, journaling, therapy, exercise, and tarot have all been the tools that I had to enact with a renewed discipline just to keep my sense of sanity. Thankfully, these tools weren’t new to me, but they acquired a new urgency as the spectre of death seemed to blanket over the country this past year.

Outwardly, the country doesn’t seem to be getting much better. The recent attempted coup, while failed, seems to foretell the battles we’ll still face dealing with the most wicked parts of this country. A militant optimist, I decided a long time ago that I would prefer to always look at the glass half-full.

I remain optimistic. I want to remain optimistic. Even though there doesn’t seem to be a flower to reach out to, and no semblance of rebirth coming. As far as ego is concerned, I can’t help but think of the group narcissism of white supremacy. A blob of prejudice so obsessed with itself, that it can’t even see its own self-inflicted harm.

Nevertheless, in the midst of this, tarot, like many other practices, remains a source of renewal, hope, and grounding. In a still quiet moment, fanning out a few cards before offers me a sense of peace. An opportunity to hold myself tightly. The prison abolitionist Mariame Kaba– states that hope is a discipline. Tarot has become a way to nurture that discipline.

The argument against optimism is usually the presupposition that it’s irrational. But I decided a long time ago that pessimism was just as irrational. The world is full of joy and sadness, and there’s no true way to quantify either. I’ve decided that it would serve me better to put my efforts, my labor, towards cultivating and nourishing hope rather than fear and despair.

I am grateful to have this practice to nurture me through the fire. I am grateful for having a practice that soothes me when I’m feeling jumpy. And I am thankful that it provides the only space in my life, where death doesn’t mean death.

Aaron Talley is a writer, activist, and educator who teaches middle school on Chicago’s south side, and a 2020 Interfaith America Racial Equity Fellow. You can connect with Aaron Talley on Twitter and Instagram @talley_marked, follow his IG tarot page on @tarot.forteachers, and read more of his work on his blog Newer Negroes.

This is the second installment in a series inspired by Tarot, you can read the first post here.

Share

Related Articles