How “The Souls of Womenfolk” Traces the Religious Lives of Black Enslaved Women

March 10, 2022

My gran, she Hannah. Uncle Calina my gran too; they both Ibos. Yes’m, I remember my gran Hannah. She marry Calina and have twenty-one children. Yes’m, she tell us how she brung here. Hannah, she with her aunt who was digging peanuts in the field, with a baby strapped on her back. Out of the brush two white mens come and spit in her aunt’s eye. She blinded and when she wipe her eye, the white mens loose the baby from her back and took Hannah too. They led them into the woods, where there was other children they done snatched and tied up in sacks. The baby and Hannah was tied up in sacks like the others and Hannah never saw her aunt again and never saw the baby again. When she was let out of the sack, she was on boat and never saw Africa again.

The above is a reconstructed memory by Sapelo Island resident Julia Governor, shared in an earlier twentieth-century interview, where she narrates her grandmother’s capture and subsequent transfer to the Americas. Stories like Governor’s are few and far in between in conventional public records – as most accounts of enslaved people tracing their roots leads them to plantation records or ship manifests, and thus, millions of enslaved people remain nameless and faceless individuals in America’s history.

These are the kind of stories Alexis Wells-Oghoghomeh, Assistant Professor in the Department of Religious Studies at Stanford University, explores in her book “The Souls of Womenfolk,” as she traces a bold history of the interior lives of enslaved Black women as they carved out an existence for themselves and their families amid the horrors of American slavery. In conversation with Interfaith America Wells-Oghoghomeh shared how her book draws upon diverse sources to explore how enslaved women crafted female-centered cultures that shaped the religious consciousness and practices of entire enslaved communities.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What made you write this book?

“The Souls of Womenfolk” is a product of deep love for the study of slavery as well as the study of Africana religions. I found that the study of religion in slavery was very central to later theories of African American religion in the United States, but there weren’t that many studies of religion among enslaved people in the United States, or really, anywhere.

In slavery studies … I saw a different phenomenon at work. There was detailed historiography around the study of gender and slavery, but not a very deep engagement of religion at all. So, the book was born out of me trying to speak to this lack in the scholarship in both slavery studies and Africana religious studies. Religion is a heavily embodied category, and slavery is also embodied; we cannot really understand the religious consciousness and performances of enslaved people without being attentive to the ways gender configured these differences in how they experienced enslavement.

Share

Related Articles

Alexis Wells-Oghoghomeh. Photo courtesy of Stanford

What are the central themes explored in your book?

The book makes the argument that enslaved African descendant women in the United States had distinctive religious culture. They have been written out of the historiography of American religion, and in a lot of ways, they are not considered a separate group. When we talk about enslaved people in the United States, we talk about them as if they’re all one monolith. They’re not. There are these very deep differences between men and women and how they experienced the institution of slavery.

The book really hinges around those differences in experiences. When I look at things like abortion, I help you understand and contextualize that first by immersing you in the material experiences of enslaved women’s sexuality and the kinds of violence that they were subjected to on a routine basis. This helps you better understand how they are assuming power over their sexuality in very distinctive ways, and the ways that their ethical rubrics are going to operate as they make these choices.

There is this woman that I talk about (in the book) — a formerly enslaved woman whose breaking point was watching her slaveholder beat her son alive, and literally kill her son in front of her eyes. When you have these women witnessing this, they are looking at their child or their infant or facing the possibility of pregnancy, and not having that child grow up in these conditions becomes mercy. Those are the most poignant experiences I am interested in looking in, because when we look and think about the history of enslaved women, the first thing that we think about are histories of sexual assault as that was absolutely a large part of their existence.

There were no boundaries around what people could do to them. So, the question for me is: how did they survive? That is the question for me as a historian when I entered into this subject. How do they make it from one day to the next? Because a lot of these people that I’ve talked about never saw freedom. How do they make it so that they want to wake up in the morning and move forward? How do they make it so that they can find joy, and they can sing songs?

I wanted to be very careful about how I depicted this because I did not want there ever to be a sense that somehow the pleasure and the joy and the moments of reclamation of power somehow superseded everything else that was happening to them. I did want to make it very clear that these were human beings living in extraordinary circumstances, who managed to continue to be human, and that is a really remarkable thing. “The Souls of Womenfolk” is using religion as a category through which we can think about the inner life and inner workings of human beings that help them assert their humanity even in the face of extraordinary circumstances.

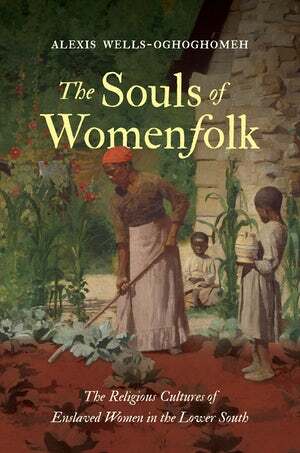

The University of North Carolina Press

What answers did you find? What did some of their religious practices look like?

To answer the question about how religiosity helps them survive, I start by really reframing how I define religion. In many ways, I am pushing against the impulse to understand religion primarily through Christian epistemological frameworks. Acknowledging that many of these people, if they were from an Abrahamic religion, were Muslims and some were Catholic, but the vast majority were practitioners of indigenous religious traditions where you have a different orientation towards what is and what is not sacred.

For me, what becomes religious in the book are the things that help people piece their lives together, piece their communities back together, and keep themselves held in the midst of these very difficult psychological, sexual, and physical circumstances. This is all a part of me trying to orient myself in the people I study, rather than imposing a definition of religion that seems legible to my audience, or even to me.

Some of the things they did were as simple as naming their children after loved ones who were sold away, or people that they might not have had the opportunity to spend a lot of time with, like a mother or a father or a grandmother. Naming someone after their grandmother was a very prominent feature of enslaved people’s cultures. The power to name one’s child is really something that I think is taken for granted in contemporary society that they did not take for granted. When they got the opportunity, they chose to link their children to their cultures. This is where we see Muslim enslaved people who continue to use Muslim names, even in the south, because they are linking these children to their cultures, even if they never touch a Quran again, and many of them didn’t.

There are also more noticeable and notable institutional cultures like shouting, which is a really prominent feature of African American religious culture, especially once you get to the 20th century. It’s a marker of African American religious distinctiveness. Shouting really is a very gendered phenomenon, in most of these spaces, the people who emote in these very evocative ways are women. The book is thinking about the ways that women are claiming space, these practices speak to us about what they hold sacred. In those shouting performances, they are changing the energy of a space, they are commanding certain spirit power there. And so, it gives us a window into not only what is important to them, but also the kinds of religious, intellectual, philosophical and cosmological lineages that they’re drawing upon, to perform in these ways.

There are all these practices that are meant to contain the trauma they faced, and those to me are religious practices, just as much as something that’s kind of more distinctively religious like prayer.

What do you want readers to take away from your book?

I want them to humanize enslaved people. I want enslaved people to no longer be these monolithic, amorphous, faceless individuals. They are complex people who had complex strivings that were thwarted by the circumstances in which they live. The book is ultimately about what they did in spite of it. It is introducing people to the study of religion and slavery. For some people, it’s an introduction to slavery.

One of the things I’ve noted from just initial reactions from people is they’re jarred by the violence in the book. I honor that response because so much of our history of slavery is based around labor, and the violence that kept people in that condition is oftentimes lost. My book and my writing are intended to prioritize enslaved women to understand just how psychologically, sexually, and physically violent this institution was. So that when you come and encounter the people in the book, you see just how remarkable they are for surviving. I want the book to be a testament to humanity, and people’s will to assert their humanity even in the midst of circumstances that were designed to make them feel less than human.