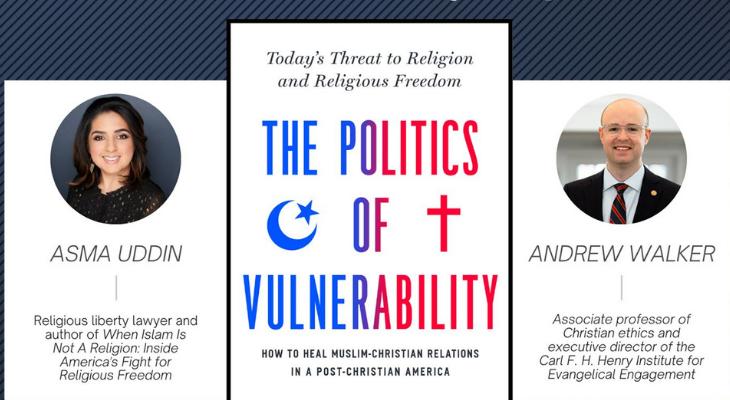

Faith and Freedom: A Conversation Between Asma Uddin and Andrew Walker

May 3, 2021

This year, acclaimed religious freedom attorney Asma Uddin and Southern Baptist Theological Seminary Professor Dr. Andrew Walker both published highly anticipated books on the present role and future of religious freedom in America. Last month, Kevin Singer, co-director of Neighborly Faith, brought them together to discuss their respective publications and the consequences of the Equality Act on religious organizations, institutions, and places of worship.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length — you can find the full conversation here.

Kevin Singer (Moderator): Asma, why did you write The Politics of Vulnerability? What’s the goal? Why are you, as a Muslim, committed to getting conservative Christians and Muslims talking about religious freedom? Why’d you do that?

Asma Uddin: I’ve been in the space of religious freedom, either as a lawyer or a writer, for over a decade, which is pretty much my entire career. While I’ve been in that space, I started seeing a bit of a disparity, both among the people I was interacting with, but also in contrast to the public discourse. The disparity was that religious freedom is really important and really good for society, but [religious freedom] doesn’t apply to Islam and Muslims, or it applies with lesser force.

And so that was what led me to think about this book—to write this book. I was thinking, “if I can somehow explain what I’m experiencing and seeing and then disseminate those findings,” that this could be really interesting—not just in terms of what’s going on with religious freedom, but more broadly what’s going on with polarization and tribalism.

At the core of my thesis is this idea of vulnerability. What is the fundamentally human factor here? What is it that we as humans are feeling and thinking that lead us to do things that might be problematic? Instead of focusing so much on just the action, take a step back and look at the human [dynamics].

What I discovered is that religious freedom, in many cases, especially when it comes to conservative Christians, is deeply tied to their feelings of anxiety, their feelings of being under siege and, in a country that’s changing in so many different ways from what they’re used to, religious freedom is really their way of expressing a lot of that anxiety and trying to protect themselves from all these changes. Unfortunately, [this] can also be weaponized.

What my book explains how religious freedom can be used essentially as a sword against the out-group, but it can also be a solution. At a time when there are so few things that we can actually agree on across tremendous differences, I think religious freedom is uniquely positioned to be that cross-cutting issue and that’s why I’m so interested in having Muslims and Christians talk about it.

KS: Dr. Walker, why does this conversation matter to you—this religious liberty for all conversation?

Andrew Walker: I teach at the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. I teach both Christian Ethics and also teach classes in public theology. One of my goals as a professor is to rehabilitate the notion that religious liberty is not simply an evangelical virtue. It’s a Baptist distinctive. You may not know that the existence of religious liberty in an American context—especially the very founding origins of America itself—Baptists were integral at the founding of America as far as bequeathing this idea of religious liberty for all people. Not just Christians, not just various Christian denominations, but all people of faith.

One of my goals as a professor is to help Baptist pastors understand the distinctiveness of religious liberty. To bring that back out into the congregations so that, when we are advocating for religious liberty for all persons, it doesn’t actually sound peculiar or unique. It’s actually just simply a fact of the matter of our Baptist heritage. And so, in many ways, I’m not doing anything… I’m not being avant-garde in my advocacy for religious liberty. I’m simply actually retrieving a tradition that I think has gotten lost. Because when you are in the majority culture pertaining to religion, you often don’t have to find yourself defending religious liberty. It’s often when you’re in the minority position.

KS: This next question is probably one of the more sensitive topics in our culture and in politics right now and that’s the Equality Act.

Pastor J.D. Greear, who is the pastor of Summit Church and president of the Southern Baptist Convention, tweeted this:

“In our lifetime, there has not been such a significant attack on religious liberty as the Equality Act,” he said. “Our gospel teaches us to live at peace with everybody in our society and that all people are worthy of respect as image bearers of God and entitled to those rights therein…We love our LGBTQ neighbors and we want to see them treated as equals and protected as citizens, but H.R.5, the Equality Act, does not do that…The Equality Act undermines rather than advances the cause of human dignity, not only punishing religious organizations, but also harming hundreds of thousands of vulnerable people whom these organizations serve. We want equity and this isn’t it. We unequivocally and categorically renounce this bill.”

Asma, how do you respond to this? When you imagine a society with a ‘politic of vulnerability’ as part of the equation in which Christian conservatives and Muslims are locking arms to protect faith and freedom, is fighting against the Equality Act what you imagine? Is that something you imagine would fit within the framework that you’ve developed here in this book?

AU: I can see the Equality Act being one of many things that Muslims and Christians can work together to oppose. Because I do agree with J.D. Greear that, yes, the Equality Act does have dire consequences for faith-based entities of all sorts. It’s going to shut out those religious voices. So, I think that, in and of itself, for the people who have traditional beliefs around sexuality and marriage, et cetera, those sorts of threats are very clear.

But beyond that, I think it really goes back to the premise of religious freedom in terms of protecting the religious quest. It’s about the spiritual quest for meaning, whether that manifests in the form of organized religion or not. Fundamentally, religious freedom provides the ability to be able to live with people of deep difference and to understand that there should be space for dissent. It’s not even just about religion. It’s sort of an example of the ability to express a belief or a viewpoint or a thought that might not be in congruence with someone else’s but knowing that you’re protected in your ability to express that and to exercise those beliefs.

And so, I think from that perspective, regardless of what individual [faith traditions] think about same-sex marriage or the rightful endeavor to protect broad human rights for same-sex individuals, more broadly is the question [of] the problematic elements of the Equality Act. I think what is at stake is the ability to create a culture in which dissent is allowed. Again, it really goes back to sifting through so much of the cultural and political rhetoric and getting to an accurate understanding of what religious freedom is and what these concerns are. All that would have to be done first, I think, in order to make this collaboration possible.

KS: Andrew, how realistic is the prospect of Christian conservatives seeking out Muslims to lock arms in fighting against a bill like this? Even with Neighborly Faith, I think we have to be honest that, with evangelicals having so much social, cultural, and political capital, we don’t want to be naive and assume Christians are just going to be pining for opportunities to cooperate with Muslims. Would you personally tell pastors, denominational leaders, that it’s critical they lock arms with Muslims, even in this particular area, fighting against a bill like this?

AW: I think it’s essential. I mean, everything Asma has said is correct about the direness of this bill. [The Equality Act] eliminates viewpoint neutrality. It says that if you don’t believe or abide by these new governing orthodoxies that you’re on the wrong side of the law. That’s going to penalize you and your institution. So, I think we absolutely should partner with Muslim organizations that have the same convictions about the nature of marriage.

The temptation in the religious liberty discussion around these issues is to treat religious liberty as a fallback— a kind of retreatist option. Like my friend, Ryan Anderson, at the Ethics and Public Policy Center talks about, religious liberty is not enough in this conversation. It’s not enough because if we think what we believe is true around gender and sexuality, it means it’s true objectively. So, it means what’s necessary is for good arguments to be advanced. To seek to persuade. To help people understand that if they may not agree with us, ultimately, on the conclusions about maleness and femaleness and marriage, they cannot dismiss us as irrational.

I, [on] equal footing, want to be a proponent of religious liberty and link arms with every organization that will stand to defend these issues, but I also want to use religious liberty as a catapult to make those arguments. To help push back against a culture that thinks this thirty-to-forty-year revolution that we are experimenting with, in terms of redefining marriage, is an unquestioned aspect of the liberal zeitgeist. I mean, this is what C.S. Lewis refers to as chronological snobbery. We are taking something that has been a bedrock pillar of human civilization since time immemorial and we’re saying that, if you don’t agree with a principle that’s been taught for the last thirty or forty years, you’re on the wrong side of history. Quite frankly, that is brazenly arrogant and religious liberty can’t just be something we fall back on. It’s something we use to say, “No, I think you’re wrong, and you may not agree with me, but you cannot call me a bigot for these issues that I believe are true.”

KS: Thank you both so much, again, for these really thoughtful responses.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this interview do not necessarily represent the opinions of the author or Interfaith America.

Amar D. Peterman is Director of the Ideos Center for Empathy in Christian and Public Life. He is also a graduate student at Princeton Theological Seminary, focusing his studies on American religious history. His writing and research have been published in Christianity Today, the Christian Century, Sojourners, Faithfully Magazine, and more. can follow his work on Twitter: @amarpeterman

Share

Related Articles

Higher Education

What Does Interfaith Engagement Mean from an Evangelical Perspective?

American Civic Life

Racial Equity

Immigrant Faith Communities On Rooting Out Anti-Black Racism