Book Excerpt: Chris Stedman on Finding Empathy in Digital Spaces

November 26, 2022

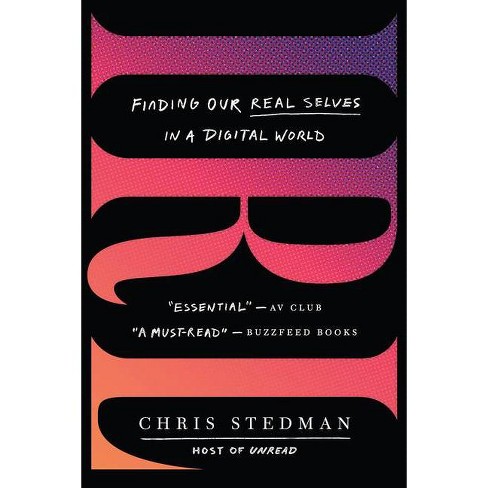

In celebration of the 10th anniversary of the publication of his book, “Faithiest,” Chris Stedman shares an excerpt of his newest book, “IRL: Finding Our Real Selves in a Digital World”.

Oftentimes, there are reasons to be weary of digital spaces, but Stedman, a professor in the Department of Religion and Philosophy at Augsburg University in Minneapolis and author of the books “Faitheist” and “IRL: Finding Our Real Selves in a Digital World ,” writes about the hope in finding connection and ultimately empathy in these social media and online spaces.

The following excerpt is adapted from “IRL: Finding Our Real Selves in a Digital World” (Broadleaf Books).

How well do you know—and empathize with—the people you follow on social media? Think about that person who followed you years ago, for reasons you can’t totally remember, and something inspired you to follow back. You still occasionally like each other’s stuff and every once in a while even respond with a comment. You’ve seen their profile picture enough times over the years that you could probably pick them out of a crowd, if you really tried. And while you don’t think of them often, whenever you see their posts, you’re like, Hey, that’s interesting. Interesting enough that you keep following.

What is that connection, exactly, and how much do you care about them? To find out, in late 2018 I reached out to someone I’d followed for about a decade, a British man named Zain, and asked if we could talk for the first time, hoping it might help me better understand digital empathy and the distances we establish and close online.

We ended up talking for hours as he opened up about his experiences growing up queer and Muslim. After our conversation, as I sat there absorbing everything Zain had told me, I was overwhelmed that just a few tweets and likes over the years had connected me to this person and his incredible story. It struck me then that there was another way to look at our digital distance—one that doesn’t just see our online relationships as less than, as shallow versions of the “real thing.” The relationships that we see as less “real” are actually just a different kind of relationship, not a worse or lesser version of the same thing.

In Twitter and Tear Gas, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Zeynep Tufekci explains that people have different kinds of social ties, including strong ties, or those we’re closest to. Strong ties are, of course, vital to our wellbeing and sense of meaning. But they are also, in some respects, easier to uphold than the social ties we have to work colleagues, acquaintances, or childhood friends. “People tend to try to keep up with those to whom they have strong ties no matter what technology is available,” writes Tufekci. But that’s not the case for weak ties, which easily disappear.

Thanks to social media, though, we can now keep up with even those we only briefly meet or aren’t very close to. The internet, says Tufekci, enables us to maintain even our weaker connections, the relationships “that without digital assistance might have withered away or involved much less contact.”

Here’s why that matters, if an important part of being human is being exposed to information that can challenge us, shape us, and help us grow: “People with strong ties likely already share similar views, so such views are less likely to surprise when they are expressed on social media,” writes Tufekci. “However, weaker ties may be far flung and composed of people with varying political and social ties.” In other words, weak ties can help us get out of our in-groups and filter bubbles—a problem social media enables, but may also be able to help us combat, if we use it mindfully.

When we put distance between ourselves and others—something we often do to feel safer and more secure—we ironically end up hurting ourselves because we isolate ourselves from people who can help us become more fully human. Online, we sometimes create filter bubbles and echo chambers when what we need is to be surrounded by people who see the world in different ways than we do. But the same tool that can allow us to wall ourselves off can also enable us to connect with a wider range of weak ties.

There’s another value in weak ties: they can serve as a bridge. Tufekci gives the example of a coworker who sees political news on your Facebook and shares it with their own social network, which includes their family and friends—people you otherwise would not have any access to. In her scenario, the coworker is what’s called a “bridge tie.” Our weak ties are more likely to bridge us to disparate groups, she points out. Furthermore, as Harvard University’s Mario L. Small explores in Someone to Talk To, research on social networks finds that people are more likely to confide in weak ties. We often turn to our digital weak ties in order to cope with deep, serious problems we feel we can’t bring to our strong ties.

While there’s reason to be concerned about the impact social media is having on our strong ties, there’s also clearly cause for celebration in light of how much more access it gives us to our network of weak ties. Weak doesn’t mean less real; our weak ties can help us become more complex, informed versions of ourselves. They can bridge us to stories and perspectives we would never have encountered otherwise, like Zain’s. We just have to be willing to walk across and bridge the distance.

The bridges we can build online to weak and distant ties are essential if you believe that understanding the experiences of people who are different from you is an important part of becoming more fully human.

Share

Related Articles

American Civic Life

American Civic Life

Interfaith Inspiration