Combating the Health Care Shortage is a Spiritual Matter

August 5, 2022

Early in the pandemic, a friend of mine, a nurse at a hospital in Raleigh, North Carolina, volunteered to leave her usual post in the cardiac catheterization lab and help in the COVID-19 intensive care unit.

To keep herself afloat mentally and spiritually during those weeks, she would write email reflections about her experiences in the ICU and send them to her community of friends and family.

“Let me start by saying it is hard to put all of this into words,” one email began. “I have vacillated between fury, helplessness, tears, exhaustion, and everything in between on a daily basis.”

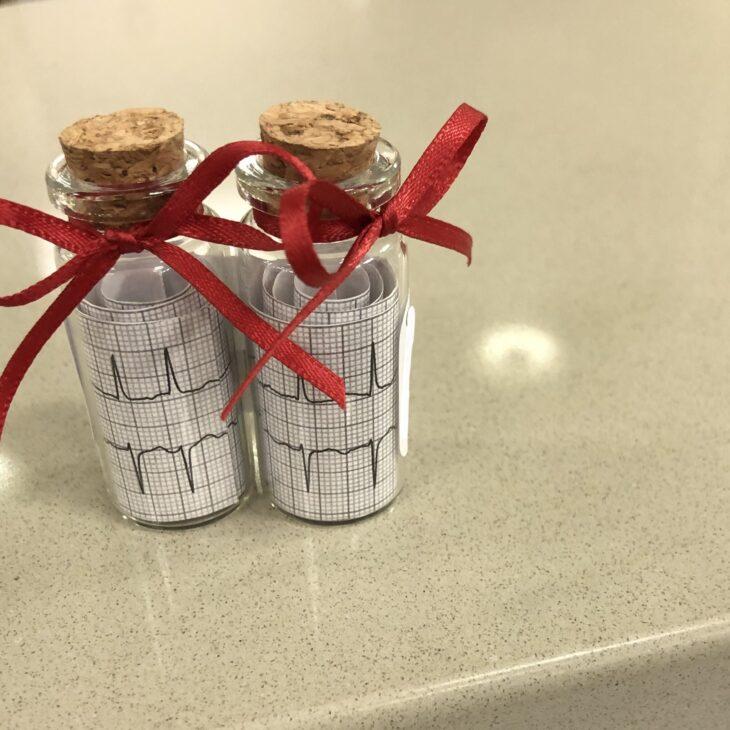

She went on to reflect on the loss of a patient: “We extubated a patient and put them on a morphine drip so they could pass away as peacefully as possible. Their family was on FaceTime in the room. A nurse was there, too, and turned off the monitor when the heart rate stopped. An EKG strip was printed off and placed in a bottle with a red ribbon to send to the family. These are the last heart beats of your loved one. We are sorry you couldn’t be with them.”

Each email concluded with a list of intentions “for those who have asked how they can specifically pray.”

As I read (and re-read) these messages, the emotions behind the words were palpable. My dear friend was someone with a strong spiritual connection to her work as a nurse — but increasingly that work was depleting her every spiritual reserve.

In the years following the onset of the pandemic, physical, emotional, and spiritual depletion has exacerbated a health worker shortage that was already plaguing the United States. In many regions of the country, this shortage is now at near-crisis levels and is only expected to worsen in coming decades.

Reversing the trend — one with dire consequences for everyone who relies on doctors, nurses, therapists, and the like — requires courageous and creative action.

“Who cares for the caregiver in these poignant times so they can be a source of comfort for others?” Dr. Joset Brown, a trauma nurse and educator at William Paterson University in Wayne, New Jersey, recently posed this question in an article about the excruciating toll COVID-19 has taken on our health care workers since 2020. I propose three answers to this question, three pathways to better care for our caregivers in these poignant times:

1. Caregivers must be equipped with tools to care for themselves. The American Nurses Association recommends self-care — which includes activities that promote spiritual well-being — as a critical tool for managing stress and sustaining “a nurse’s capacity to provide compassion and empathy” to patients and themselves. Spiritual self–care can take the form of contemplative practices that help caregivers navigate anxiety or conflict mindfully; reflections on how religious or secular beliefs can help caregivers maintain equanimity in the face of illness and death; or mind-body exercises like meditation, yoga, or certain forms of prayer that aid in stress reduction. But caregivers cannot be expected to develop a spiritual toolkit on their own. Rather, best practices in self-care should be promoted by health care systems, professional associations, and even training programs.

2. Caregivers must have space to care for one another. “Acknowledging and processing our experiences is rarely part of the medical profession even as rates of burnout and moral distress in health care continue to rise,” Dr. Anu Gorukanti, a pediatric hospitalist, wrote one year into the pandemic. Recognizing the spiritual toll her work was taking, Gorukanti and a longtime friend, Laura Holford, a registered nurse, set to work building a space where caregivers could process grief, loss, and other hardships with one another. Introspective Spaces is an organization that “empowers women in health care to live authentic, engaged, and meaningful lives rooted in caring, contemplation, and courageous action.” This mission is achieved by providing virtual interfaith community circles, mind-body-spirit contemplative challenges, workshops and retreats, and more. Spaces like these, Gorukanti asserts, enable health workers “to continue finding meaning and moments of joy in their patient encounters and improves their resiliency in the workplace.”

3. Caregivers must be cared for by the communities they serve. Health care systems have a vested interest in creating the conditions for spiritual wellness among their staff. After all, according to the American Nurses Association Code of Ethics, “activities that broaden nurses’ understanding of the world and of themselves affect their understanding of patients.” In higher education, and increasingly in corporate spaces, providing space for spiritual support and expression is already front of mind. Many of these institutions provide multifaith prayer rooms, floating holidays, and faith-based employee resource groups. Offerings like these can go a long way in extending care to our caregivers, but alone they are not enough. Equitable pay, flexible scheduling, and adequate staffing are also critical investments that make it possible for health care workers to move beyond a focus on surviving to a place of holistic thriving.

It is incumbent upon us all to imagine better ways of attending to the spiritual needs of our caregivers, who give so much of themselves to ensure our health and well-being. This is one crucial step in stemming the looming health care crisis. Moreover, we must advocate for real change in the ways we support health workers — within and beyond their workplaces — because they are advocating for us, every day and at every bedside.

Shauna Morin is a Strategic Initiatives Consultant at Interfaith America.

Share

Related Articles

American Civic Life

American Civic Life

Announcing Interfaith America’s 2024-2025 Cohort of Faith & Health Fellows

American Civic Life