Truth Matters: Facing the History of Native American Boarding Schools

November 22, 2021

When researchers uncovered the unmarked mass graves of more than 1,000 Indigenous children at former residential schools in Canada earlier this year, a global public outcry followed. The news also amplified efforts for the U.S. to launch a nationwide investigation to unearth its own history of cultural and physical abuse at federal and church-run boarding schools for Native American children. A bipartisan bill to launch a national investigation is now before Congress.

Last week, two leaders of these efforts — Christine Diindiisi McCleave, a citizen of the Turtle Mountain Ojibwe Nation, and Vance Blackfox, an Indigenous theologian and citizen of the Cherokee Nation — held a public conversation on the history of the Indian Boarding Schools in the U.S. Acknowledging that many of the boarding schools were run by religious institutions, they also spoke about how churches might play a role in the journey towards truth, justice and healing.

The conversation was a part of the 2021 Vine Deloria Jr. Theological Symposium at the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago. Deloria, a Standing Rock Sioux who died in 2005, was a nationally known writer and lawyer who earned a master’s degree from the seminary in 1963. At the symposium, presenters talked about the intersection of Indian boarding schools and theological Christian education as well as the work being done across the United States to bring truth and healing.

Share

Christine Diindiisi McCleave

No image description available.

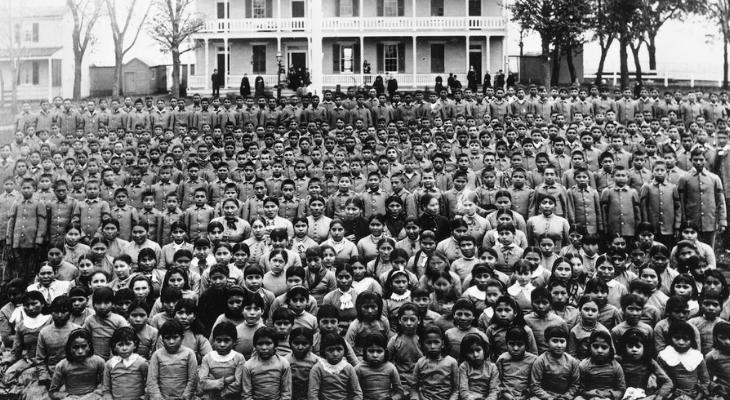

The dark history of abuse in boarding schools in the U.S. can be traced back to the mid-19th century, when government policies called for Native American children to be removed from their families and tribes to schools that demanded the children abandon their language and cultural practices. The stated intention was nothing less than cultural genocide. In the words of Lt. Col. Richard Henry Pratt, founder of the nation’s first Indian boarding school in Pennsylvania, the goal was to “kill the Indian, save the man.”

Evidence of the scale of abuse continues to grow. Last week’s symposium took place the same week researchers in Nebraska announced they’d identified the names of 87 children who died at the Genoa U.S. Indian Industrial School between 1884 and 1934. Genoa was one of the largest in a system of more than 300 boarding schools run by the U.S. government and churches in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

McCleave is CEO of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, a non-profit that aims to understand and assess the ongoing trauma caused by the U.S. Indian Boarding School Policy. The organization states on its website: “Between 1869 and the 1960s, hundreds of thousands of Native American children were removed from their homes and families and placed in boarding schools operated by the federal government and the churches. Though we don’t know how many children were taken in total, by 1900 there were 20,000 children in Indian boarding schools, and by 1925 that number had more than tripled.”

Below is an excerpt of the conversation between Blackfox and McCleave. This transcript has been edited for clarity. You can listen to the full conversation here.

Vance Blackfox: Can you tell us about the work NABS does?

Christine Diindiisi McCleave: We found a list of about 367 [Indian boarding] schools in this country. And that list is still growing and changing as (more information comes from) independent research. When it comes to knowing how many children went to the schools here in the U.S., we don’t know, but we can estimate at least double the numbers in Canada. What we do know is that looking for the records to try and figure out the numbers is also proving to be very challenging. There are records from federal-run boarding schools in the federal archives, and anyone can access those as they’re part of the public record, but the church-run boarding schools are proving to be a very complicated issue because a lot of the churches don’t know where those records are.

One of the other things that we’re doing is that we’ve continued to work for a federal Truth Commission in this country. And thankfully, there is a bill that’s in Congress right now. It’s both in the House and the Senate. It’s a bipartisan bill that has a good number of supporters and co-sponsors on both sides of Congress. That truth commission would build off of the investigation from the (Department of) Interior, and it would take a step further to actually collect testimony from survivors and descendants, like in Canada. They held regional hearings, and they heard directly from those students, or the children of those students.

So, that’s what we are doing. We’re continuing the research; we’re building a digital archive for the records that we do have access to so that people don’t have to travel all around the country. Particularly for some of the students who went to more than one boarding school, we want them to have one central repository, and for researchers to be able to analyze and compare one boarding school to another. I think it’s important for us to be able to look at the big picture in order to fully understand the impacts of the boarding school experiences and the boarding school era.

VB: What do you think the church can do to be helpful in the work NABS is doing, or in the boarding school healing movement in general?

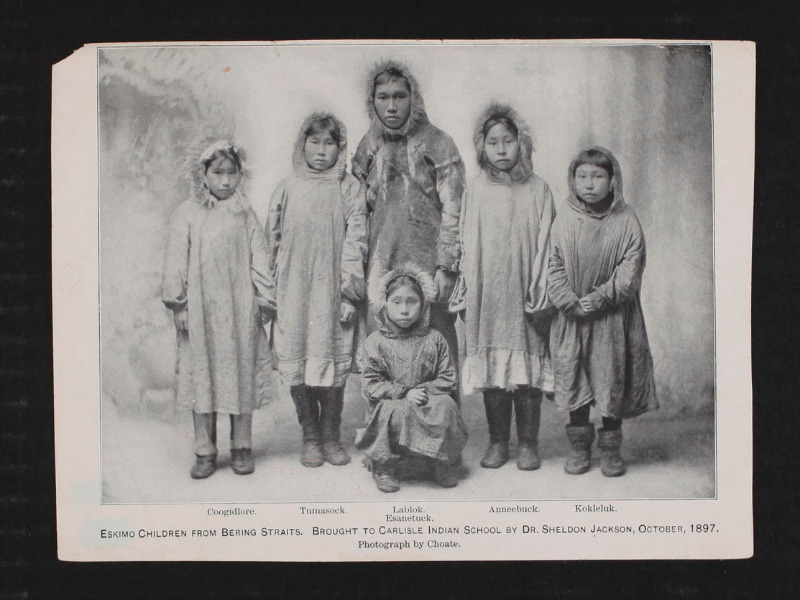

Alaska Native children brought to the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, 1897. Photo: John N. Choate. Image Courtesy of the Presbyterian Historical Society.

CDM: In 2020, I wrote an article called “The Catholic Church and U.S. Indian Boarding Schools: What Colonial Empire Has to do With God.” Here’s an excerpt:

“…Since the early 1800s, the Catholic Church and other religious denominations have been inextricably linked to the Indian boarding school history in the United States. Additionally, the US Indian boarding school policy was developed at the height of the US Indian Wars aimed at removing indigenous inhabitants of the land for westward colonial expansion. Therefore, the Indian boarding schools were at best colonization and forced conversion and at worst genocide… it’s not enough just to not physically or sexually abuse native people or children. The churches must stop the spiritual abuse as well. The Church must confront its abuses to Native Americans in the US and repent and atone for its transgressions. They must repudiate the doctrine of discovery which continues to fuel colonial empire to date, and they must commit to a full reckoning of their boarding school pursuits over the last few centuries”

It’s really about examining how the church has furthered this idea of colonial empire. How individuals inside and outside the church have benefited from this attempted genocide from the removal of lands from the racial capitalization of human beings. And so basically, I’m talking about genocide and slavery. Sometimes there’s this defense or this response of, well, that wasn’t me. Why should I be responsible for what my ancestors did? While we’re not expecting people to go to jail for what their great grandparents did, we are expecting them to fully examine how they benefited from those crimes against humanity and to reverse the scales of justice towards equity. A lot of wealth has been built in this country off stolen lands and stolen labor. And what are those wealthy people doing today? To make things right to make reparations to repent and atone to actually deliver justice? This goes beyond just colonization in the United States. This is a humanitarian issue.

VB: Are there any examples or stories of voluntary reparations happening from Church properties or wealth back to Native Communities?

CDM: I think a really good example is in the second Chippewa Tribe in Michigan. The boarding school building there for the Mount Pleasant Indian Industrial Boarding School was sold back to the tribe for $1, so essentially given back to them. But that question about reparations is of course a complicated one.

Who is receiving the apology or the reparations? And when you identify people who call themselves victims or survivors, I think it’s important to ask them what they would like in terms of justice and healing, because it may vary. In Canada, the Truth Commission was the result of a class action lawsuit that was settled by the Canadian government, and in addition to establishing the commission, they interviewed victims of abuse in those schools and assigned a dollar amount to award them for the harms. And that process was really difficult.

What we’ve heard from people after the fact is that it was both confusing and demeaning and enraging to have a dollar amount assigned to abuse. Some of those people said no matter how much money they give me, it doesn’t change the fact that I’m haunted by nightmares. So, yes, monetary reparations can be effective in some cases, but I don’t think that they are the means to an end when it comes to healing. And so, it really will involve, you know, a community-by-community case basis or an individual-by-individual case basis in terms of what the harms were and what they feel reparations would look like.

VB: How can people from diverse faith communties play a role in this healing process?

CDM: We need everyone to be committed to truth and healing. As I mentioned before there’s a bill in Congress right now. Everyone should be contacting their legislators, not just Native people. Because this is a history that we need to fully examine and face as a country. And so there’s plenty that allies can do, whether you’re a person of faith or not, this is an issue for all of us. And so it will take all of us moving forward to truly transform our society.

For more on the legacy of Native American boarding schools, the documentary Independent Lens – Home from School: The Children of Carlisle airs Tuesday, November 23 at 10:00 pm on WTTW Chicago and will be available to stream.