“Together yet separate” went the mantra that encapsulated the two year out of body experience that was the COVID-19 pandemic.

The well-meaning phrase, meant to preserve a semblance of social solidarity, was more easily uttered than lived in reality. Zoom and widespread use of social media could not mitigate, but certainly amplified, the pandemic’s deleterious effect on our capacity to build community and feel whole within ourselves. No longer able to follow non-verbal facial cues or physically embrace, division becomes the order of the day: a divided self, an alienated society, and a divided world.

Now, as the pandemic turns endemic and other crises fill the void, the question of how to restore the integrity of our selves and the communal functioning of our body politic is even more urgent.

As a pastoral leader in a religious community, I’ve begun to approach these vital questions of alienation and division through the religious idea of pilgrimage, an ancient practice with a deep and broad heritage across spiritual and religious traditions such as the hajj to Mecca or visits to Hindu holy sites in India. In these traditions and others pilgrimage has been used as an intensive period of remembrance, reflection, and renewal, usually in transitioning to another phase of life. But the best way to uncover the gifts of pilgrimage for this moment is not simply through the written word or lecture, but to take up the practice oneself.

Two Personal Pilgrimages

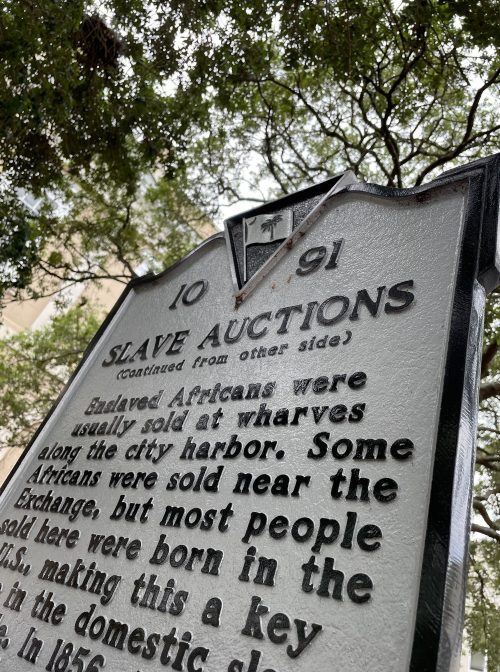

And this is what brought me to Charleston, South Carolina, for the first of two pilgrimages I have undertaken this year to gather wisdom for the communities I serve as they seek healing threadbare relationships and wearied hearts in these politically, socially, economically, and ecologically disruptive times. I was traveling with a large group, the majority of which came as members of Trinity United Church of Christ, a historic 6000+ member African American congregation on Chicago’s South Side, led by nationally recognized pastor the Rev. Otis Moss III. The Est. 1619 Pilgrimage, curated for us by Lisa Sharon Harper and her organization Freedom Road.us, empathetically led us through difficult site visits and discussions surrounding the advent of U.S. slavery and Jim Crow segregation that have left indelible marks on the African experience in our nation.

As I expected, this first pilgrimage was not simply one of the intellect, but a journey that sunk deep into my bones, recalling what Dr. Lyricia Hawkins aptly calls “Embodied Solidarity.” On just our second day, I felt that embodied experience most palpably on the grounds of Boone Plantation, with the sweltering heat of the sun climbing up the horizon and the arresting ringing of cicadas from the oaks trees which stood like colonnades over the grand entrance.

As we made our way to the modest brick cabins in which enslaved Africans toiled and lived, we were told that brickmaking, in addition to cotton, rice, indigo, and pecan production, was the economic foundation of the plantation. In fact, at one point in the 18th century, more bricks were produced here than in any other place in the state of South Carolina. Artifacts found in the cabins themselves indicate that young children, whose hands were evidently small and slender enough to supply critical emulsifiers, also were part of the brickmaking. Their finger imprints, frozen in time but still speaking, can be found in surviving bricks. For me, they harkened my mind to biblical images of Israelite brickmaking in service to Egypt’s voracious Pharoah. The book of Exodus tells this signature story of the flight from Egypt and the formation of a people holy for three religious traditions and ensconced in the mythology of liberty.

As I encountered this and other sites, as well as the stories of individuals who gave them meaning, an extraordinary thing occurred. I began to move out of my mind, the world of cognition, where I intellectually assent to disturbing facts, and into my body, where I began to feel them in ways that I could not jettison or contain. I experience the emotion 19th century African American theologian Jarena Lee said when she felt called to preach: a fire shook in my bones.

Inner Journeys

The pilgrim is in search of embodied knowledge. They are beckoned out of their mind and drawn toward the wisdom that the body in motion with its tactile senses, has to tell us. As American Trappist monk Thomas Merton remarks, “The geographical pilgrimage is the symbolic acting out of an inner journey.” On my inner and outer journey, I encountered in Charleston places of great pain and suffering. As I did so, I needed to let my body grieve, lament, lock hands with fellow sojourners to absorb strength – and then to clap and sing songs of resistance.

But if pilgrimage is about being fully in the body that travels, it also about being grounded on the path being walked. The enslaved at Boone Plantation built the very edifices in which they were imprisoned. Unlike the slaveholders who managed their land remotely with the use of an overseer, the enslaved Africans actually lived, toiled, and died here in a work camp with eerie parallels to the concentration camps of Nazi-occupied Europe. And yet, they could never own or have autonomy over these grounds. What happens when the ground beneath our feet is unstable and the work of our hands not our own?

In such a pilgrimage of pain and perseverance, we encounter these places where the ground cries out with stories of suffering, asking us whether these lands can be redeemed. For now, I have no answers, just subtle suggestions.

On day four, a broken air conditioner, and a detour to a roadside gas station, afforded us a chance encounter with 91-year-old Curtis Inabinett, a local Charleston County legend with a highway named after him. A Korean War veteran, Mr. Inabinett sought land for a market in the late 1960s so that his cooperative of Black farmers spread throughout the South Carolina sea islands could find a central location to sell their produce. Turns out the land was held by white owners who offered it up for the Klan to gather. The owners unwittingly sold it to Black farmers and after a tensive standoff decided to cede the claim of the land to Mr. Inabinett’s confreres. Preparing the land for use, they uncovered an old cellar and artifacts with confirmed this land as a site of the 1739 Stono Rebellion in which enslaved Africans, many Angolan Catholics, took to arms and marched with a banner marked “Liberty” with hopes of reaching Florida where Spanish authorities promised their freedom. Mr. Inabinett had rested the site of the largest slave rebellion in U.S. history from the possession of the Klan. A highway marker now marks the spot that is an important stop for any journeyer seeking to understand how a place once defiled can be redeemed.

As I turned to the next pilgrimage, a decidedly religious walk on the famed Camino de Santiago in Spain, questions still remain about the power to redeem suffering places, but this I have learned from my Charleston journey:

Pilgrimage at its best is not simply about the reclamation of land through walking it. Nor is it only about the renewal of our individual body, mind, and spirit. It is ultimately about the renewal of our collective sense of community and purpose through ever changing and troubling times.

Rev. Joseph L. Morrow is Associate Pastor for Evangelism and Community Engagement at the Fourth Presbyterian Church of Chicago. Joe is a Sacred Journey fellow with Interfaith America and has worked extensively in congregational, non-profit, higher education, and corporate settings.