(RNS) — A newly published collection of photos highlights the range of religious practices of African Americans — inside and outside traditional sanctuaries.

“Movements, Motions, Moments: Photographs of Religion and Spirituality from the National Museum of African American History and Culture” is a compact volume spanning the 19th through the 21st centuries and featuring grassroots people expressing their spirituality.

The book, part of the Double Exposure series of the Smithsonian museum that opened in 2016, is to be released Tuesday (Jan. 10).

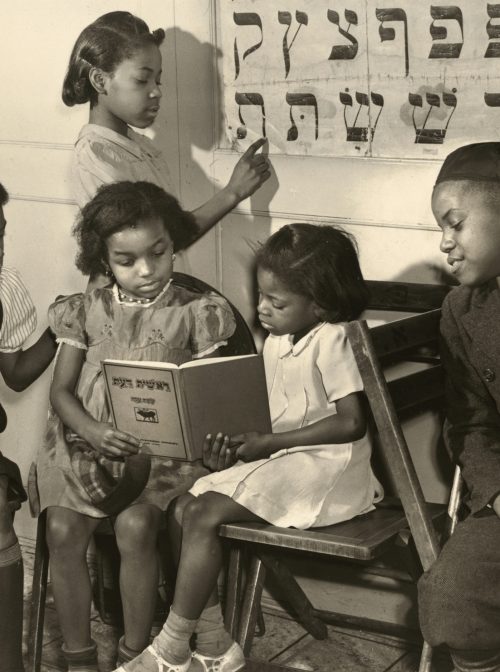

The captions and other writings that surround its more than 65 photos explain how the rituals and remembrances captured in the book reflect Black history through its diversity of spiritual traditions, from salat, the five-times-a-day Muslim prayer, to the observance of Rosh Hashana, the Jewish new year.

For example, the 1981 image of a baptism amid the rolling waves of Lake Michigan echoes the practices in creeks and waterways that were used in the Deep South before many African Americans headed north during the Great Migration earlier in that century. A 1919 photo of women and men outside Vernon African Methodist Episcopal Church was taken two years before the church was burned in the Tulsa racial massacre — and eventually rebuilt atop the surviving basement.

Here is a slideshow of a sampling of the book’s photos:

The book features well-known figures such as Dallas’ T.D. Jakes and New York’s Father Divine as well as trailblazing female religious leaders. Myokei Caine-Barrett is shown preparing for ordination as bishop of the Nichiren Shu Order of North America in 2014, when she also became the first person of African American and Japanese descent to head that Japanese Buddhist organization.

In contrast to the long and persistent history of lynching photos — that were sometimes distributed as postcards — the volume includes the integration of dignity at the time of death. One lesser-known photo depicts an honor guard of women beside the casket of Harriet Tubman in 1913 and another captures mourners in line in 1965 to view Malcolm X’s coffin, where his body was encased in a traditional white linen shroud.

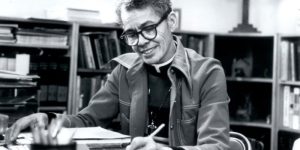

The book also demonstrates — in facing pages — the changing look of religion-related protests. A photo of young activist John Lewis kneeling in prayer with other civil rights workers in 1962, a year after he was ordained a Baptist minister, is featured across the fold from public theologian Rahiel Tesfamariam pictured in St. Louis, a year after Michael Brown’s death, wearing a T-shirt that reads “This Ain’t Yo Mama’s Civil Rights Movement” in 2015.

The book’s photos are both historic and up to date, featuring then-Archbishop (and now Cardinal) Wilton D. Gregory wearing a “Love Thy Neighbor” mask at the 2020 “Red Mass” in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Rev. Courtney Clayton Jenkins preaching a virtual sermon to almost empty chairs — save the images of her congregants taped to the seats —at Cleveland’s South Euclid United Church of Christ that same year.

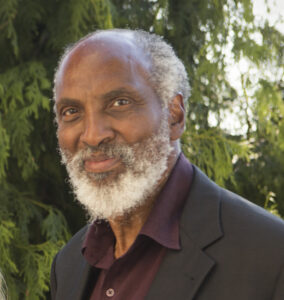

“It is our hope that after viewing these images, Black religious expressions long obscured will be more accessible, and no longer rendered invisible, nameless, or inaudible,” wrote Eric Lewis Williams, the museum’s curator of religion, in an essay that accompanies the photos.