October 18, 2022

Scholar and attorney john a. powell shares how a childhood marked by rupture inspired a life dedicated to building bridges.

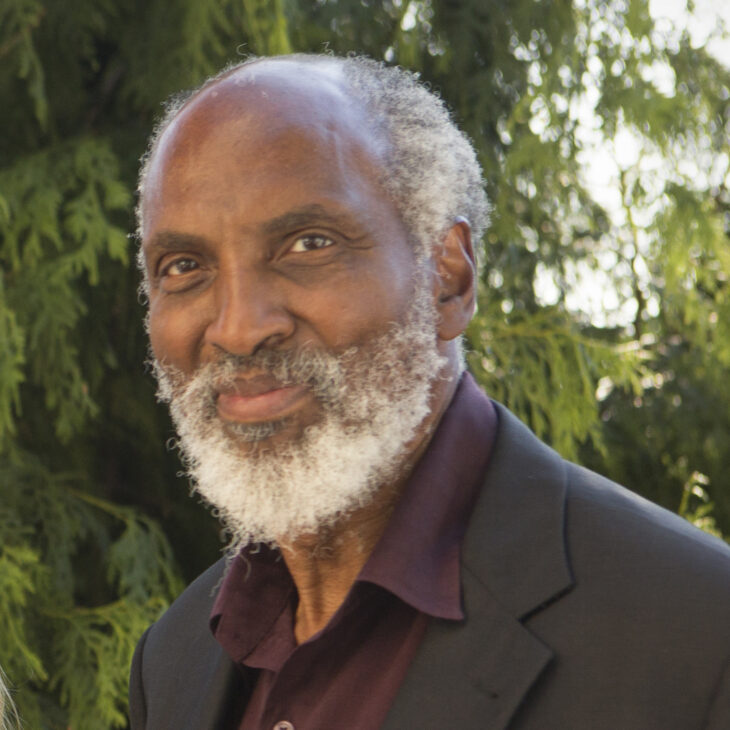

john a. powell holds the Robert D. Haas Chancellor’s Chair in Equity and Inclusion; is a Professor of Law, African American Studies, and Ethnic Studies; and leads the Othering & Belonging Institute at University of California, Berkeley. He tells Eboo why “bridging,” building connections with others, is the crucial, hard work of our time.

john a. powell (who spells his name in lowercase in the belief that we should be “part of the universe, not over it, as capitals signify”) is an internationally recognized expert in the areas of civil rights, civil liberties, structural racism, housing, poverty, and democracy. He is the Director of the Othering & Belonging Institute at the University of California, Berkeley, and appears regularly in major media to offer expert insights on a host of issues.

Receive funding for your own intentional reflection or for hosting conversations about the podcast.

How do we live together when we profoundly disagree?

Eboo Patel: This is the Interfaith America Podcast, and I’m Eboo Patel. I first met john powell in 2019. We had lunch near the campus of the University of California at Berkeley, and I was taken by the combination of his kindness, his calm and his wisdom. Simply being in his presence made me want to be a better person, not in a way that made me feel bad or guilty for who I was, but in a way that made me feel the possibilities of being human, of the things that we are all capable of.

For john, the most important of those is bridging, connecting with other people in a way that helps them feel like they belong and helps you feel like you belong, because being human means we belong together. john, who spells his name in lowercase letters as a way of signifying that we humans are part of the universe, not over it, serves as the director of the Othering and Belonging Institute at UC, Berkeley.

It’s a research institute that brings together scholars, advocates, community leaders, policymakers and others to bridge across differences, to promote belonging and to transform our world into a more equitable and inclusive place. I was a fellow of the institute in the academic year 2021-22. john, speaks, writes, consults, creates any mentors, people like me.

john and I know each other through a variety of groups that focus on bridging, including the New Pluralists Fellowship where john is viewed as a Obi-Wan Kenobi figure to people who want to be Jedis and bridging across difference. In this conversation, as with every conversation on the Interfaith American Podcast, I asked john about the religious ideas that underpin his commitment to bridging. He shares some intimate details of the spiritual journey that led him to bridging work. It was a story that deeply moved me. I think you will be moved to.

john, the purpose of this podcast is to speak to people who I greatly admire about how religion and faith impact their work in the world and their lives, including people who say overtly that they don’t organize their lives around religion, and yet it clearly has an influence. With you, it’s how much you talk about your father and what you talk about. I think I haven’t heard an interview with you where you haven’t spoken of your dad and his faith. You experienced really tough things with him.

The story about the furnace exploding and burning off every hair in his body and hospitals not taking him in because he was a Black man. You end that story by saying, “And yet he radiated nothing but love.” You tell this story about going through a really hard time in your life, you just were overwhelmed by social justice work you were involved with, and your dad said, “Yes, but you’re not alone, john, you have God.” Your next line is, “I don’t organize my life that way, but I appreciated hearing that.” I’m just curious, what of your childhood faith or your father’s example stays with you even if it is not precisely how your father lived his life?

john powell: Well, thank you, Eboo, it’s so great to being with you and I so admire your work and learn from you. I hope to continue to learn from you and be in relationship with you.

Patel: I appreciate our friendship.

powell: Yes, my father, actually it’s interesting, when you mentioned that, it makes me think that my father and mother had like a storybook relationship. They met when they were kids. I think my mother was 14 and my dad was 16 and they married two years later and had nine kids, and struggled. They were sharecroppers in the South, and they experienced a lot of discrimination. If I were to tell you about all the difficulties they experienced, you would think, “This is a hard, tough life full of trauma, full of othering.”

If you were to meet my dad, and my dad and mom have passed now, it would be like, “Wait, this life you just described and this person, they don’t quite fit as you said, this person is emanating, just radiating love,” and people used to come over and just to be with my parents. My family already nine children, was an extended family, because literally, people would come over and just hang out to be with my father and mother.

My mother died earlier, it’s very hard, and then my dad died about 20 years later. What I find the most is that even a ruptured family, which in my family I was ruptured from my family for a number of years, but I still was connected and just profound love, and in the sense it prepared me for a lot of the work I’m doing now, because we did not always agree conceptually. We didn’t always agree in terms of faith.

Patel: Was that the crux of the rupture?

powell: I think it’s complicated. I think the ruptured part, my father was a minister of Church of Christ, and the church was not something he did on Sunday, the church was his life. Religion worked for him. Some people that– You see someone who talk about religion, but you don’t see it manifest in their life. It really was how he experienced his life and the whole family.

I was born in the church, I didn’t join it, I was born in it, but I was also very curious what we might even call it, intellectual, but I didn’t think of this intellectual. It’s like curious about the world, curious about people and an early reader. When I was eight or nine years old, I started reading about the Chinese and other parts of the world, about the Chinese. From my reading, it became clear to me that they were not going to be part of the Christian faith.

I lived in Detroit in a Black community, so I’d never had even seen a Chinese in real life. I had this deep concern and it’s like almost a billion people that they were going to go to hell. That was the teaching of our church. At the end of every sermon at the church, every Sunday, the minister or person giving the sermon would say, “Does anyone have any questions?” Later I would come to understand that was a rhetorical question.

[laughter]

Patel: Right.

powell: No one had ever asked the question in my entire 11 years of being in the church as I can recall. I stood up and there was an audible gasp, and the minister, and I remember saying, was, we called him Brother Manuel. He said, “That’s all right, that’s all right, Brother powell, what’s your question?” I said, “What’s going to happen to the Chinese?” He fumbled around for about five minutes trying to find something in the Bible that helped assuage my concern. It ended up, he said, “Don’t worry about it.” I never went back to church.

Patel: Sounds like the beginning of a rupture.

powell: That was the rupture, and my father, to him, as he understood the church doctrine, if someone fell away, you were not supposed to have fellowship with them. Literally for the next four or five years, my father and I did not have fellowship, if you will. That was very painful and very important in terms of my growth, and so I’m at a very critical stage in my life in this cocoon in the sense that I had been in, a cocoon of love and relationship and very close to my family was ruptured.

There was periods of time when I didn’t even know if I would emotionally or psychologically survive. When it start to heal, it took years to heal, but when I came out of it, when he came out of it, I was a different person, in a sense, I had grown up in the house with my family, but not with my family. On Sundays they would probably run to the car for the church and they would leave me a list of chores to do to make sure that I wasn’t just enjoying myself. It’s like a bad movie in a sense. This is again, a family that was just deeply grounded and embedded in love.

Patel: Wow, is this the beginning of john powell, the bridger?

powell: I think it was, and in some ways, my first response, which you might imagine was just being pissed, [laughs] not bridging at all, but also still searching, and so in a way, having been pushed out of one set of ways of approaching life and not having a community where community was extremely important, I started searching, not just for people, but for some ideas, some ways of experiencing the world that made sense to me. I remember people that one time when I left at 11, I was still very much a believer in the Christian God.

I thought I was going to go to hell too. One day I’m praying or talking to God and I say, “I do a lot of things wrong, I can be a little turd sometimes, but I’m not doing this for me. To me, this just seems fundamentally wrong.” The idea of deeply othering people at this sense, to the extent that they are, not only maybe not human, but they’re consigned to hell.

It’s not that they were going to hell, from my perspective, it’s that they never had a chance to doing anything different. They never had a chance to actually even adopt the Christian faith. If that had been the case, I don’t think I’d ever left. I wasn’t overly concerned about, “the sinner” that was going to hell who lived down the street from the church but choose not to go, but I was very concerned about a whole group of people that I never knew personally.

Patel: I feel like the seeds of the john powell that I know, and that much of the public knows, this extensive circle of concern, it’s not like there was nothing for you to worry about, about yourself and your own community growing up in the area you did as a Black kid in a Black community, it’s not like there weren’t intense concerns all around you, and here you are concerned about a billion people on the other side of the world, and you have this very principled stand and it creates a rupture, but you’re standing on principle and yet there’s this yearning for, at least at some point for bridging. Can we disagree and still be in relationship? Which I just feel like is the heart of who you are.

powell: Yes, and I feel very fortunate. I feel fortunate to be part of the family that I’m a part of. As we worked to make those bridges years later, I feel like my family, particularly my mother and father, really worked hard. I wasn’t fully cognizant of how hard it was on them. I was very aware how hard it was on me, but in retrospect, I realized this was really, really painful for them.

That they too were living out their values. My dad dropped out school in the third grade, my mom finished high school, so they weren’t “intellectuals” in the classical sense, but I’ll give you an example, that like I said, we had eight brothers and sisters, and I remember one point saying to my mom something like, “Was it ever an issue for you having nine kids and was that a burden?”

Her response was, with complete sincerity, “Children are gifts from God,” and our family organize around kids in a really beautiful way, even today. I remember another time my dad had been in the hospital quite sick, and he was recovering, and we were going to see him, and after a couple of days he says, “Where are all the kids? Where are the young people?” We said, “Oh, we’re trying to give you some time to get better and rest.” He said, “No, bring them here.” This is saying that I like, which is that love goes places where understanding cannot.

Patel: Yes, so beautiful.

powell: The love in my family and the appreciation, I started meditating, and as I said, my family was fairly traditional in some ways conservative Christians, but I remember going upstairs and creating a space to meditate with my dad. Not because he wanted to meditate, he wanted to connect with me. He was like, “What do you do? Meditation? What is that? Is that the same as prayer?” I said, “Not exactly.” He is sitting there trying to connect with this practice, this extremely foreign to him.

In the narrow sense, he never did. In a profound sense he was already connected, but he was using that to bridge. He was using that to reconnect with his son. Just one other story about this, I have two biological children and the mother and I never married. We lived together. We had a very wonderful relationship. We’re still good friends. My kids are grown now and have one grandchild, but there’s a period where I go back to visit my family and my mom and dad would say, “You can’t sleep in the same bedroom because you’re not married.”

This is a serious relationship, a loving relationship, and I say, “I’ll stay someplace else. I’ll stay with one of my siblings, or I stay in a hotel. I respect the way you organize your house, but I have to respect the way I organize my family as well.” This went on for a number of years and it was extremely painful because of the kids. Then my mother wrote me a letter and the letter says something like this, “I see how you conduct your life. I see how you relate to your family. You say you’re not married, but I believe in the eyes of God, you are married. You can now stay with us.”

Patel: It’s beautiful. You are seeing each other trying and you are giving each other credit for the attempt, and you’re adding credit. You’re like, “I’m going to take the love currency out of my pocket and put some in yours.” It just feels like we live in a different era now from that. To offer another example, if you listen to all of the interviews that you’ve done, you talk about your father and his faith, and it’s almost always with a sense of admiration and love. You very rarely tell the story of rupture, and yet between the ages of 11 and 16, you didn’t talk to your parents very much on account of their view of religion and your principle stand in a different direction, and yet that is not the lead story for you. I’m just curious about that.

powell: It’s actually interesting as I got older, I really respect my parents and particularly my father in this instance, in a sense for the rupture itself. He was trying to live his faith no matter where it took him. I’m the youngest son, I know that my parents love me profoundly, and yet they were struggling with trying to have a relationship with me and live their faith. I respect that tremendously. To me, it was both the rupture, it was also a gift in many ways. So I can say, if I just chronicle events in my dad’s life and even in my own life, it would sound like, “Wow, that’s really hard,” but the foundation was so wonderful.

Patel: It is an ability to see the world. There’s the great line by Marcel Proust that the true journey of discovery is not in discovering new landscapes, it’s in developing new eyes and a set of eyes that look upon one’s life as a sharecropper and says, “I’ve been blessed by God,” a set of eyes that say, “You have divided from me because of a narrowly understood idea of faith, and yet I see you trying and I know your love.” I just think that that’s a powerful set of eyes. I’m curious, how important do you think that is for the work of bridging?

powell: I think it’s extremely important. I think it’s important, not just in terms of how one sees the world, but how one sees other people, our ability to actually love. I don’t think– My son said this to me, he said, “I don’t want unconditional love.” He was saying in a sense, I want you to love me for my efforts, for the things I’m doing.

There is also a place where we just love each other, we just care about each other. You don’t have to achieve, you don’t have to measure up. One of the things I’ve said to many people is that religion worked for my dad and worked for the family. We’re sitting around a Saturday afternoon several years ago, and my dad says, “Since everybody’s here, let’s just take time to say what we’re thankful for.”

We go around the room, literally, and one sister says, “I want to thank God for– I had cancer and I recovered and I learned so much, but to your point it wasn’t like I’m devastated because I had cancer. People talked about things that could be seen as traumatic or devastating, but in every instance it was turned back to, I learned something from that and God blessed me,” and I’m like, “Whoa.”

Patel: In my experience, religion is the great changer of eyes. You’re telling the same story, that in the experience of your parents and the experience of your sister, it is a set of eyes shaped by a deep faith. Where do you get your eyes from?

powell: I think in many ways the grounding of the teaching, not the teaching itself, resonates deeply with me. I believe people are profoundly connected to each other and to the earth, profoundly. I tend to be pretty stable, not many lows, but when I am feeling low is that I worry about the way we’re treating each other, the way we’re treating the earth.

Later people would say to me, “Why do you care about the Chinese? They’re racists. They don’t even like Black people,” and it’s like, that’s not the point. I think about that now when I think about what’s happening in Ukraine and the complexity of it. I think I really get that from my family, a lot from my dad. I’ll tell you one last story, my son–

Patel: I could go on like this all day, but, yes.

powell: My son, who’s for the most part I’d say atheist, maybe he slips over into being agnostic sometimes, but he’s not certainly a person who would define himself as a person of faith. When he was in his early 20s, he was going through a very difficult time. He was going to college and having crisis, I don’t know if it was existential or not, but it was definitely a crisis. He comes home, which was Minnesota at the time, he’s depressed, locks himself in his room, won’t come out, not eating well.

I’m worried about him, so I say to him at one point, “You have to get out. If you’re going to stay here, you have to do three things. You have to look for a job, you don’t have to get one, but you have to look. You have to get professional help, see a therapist, and you have to go visit your grandfather.” He objected to all three, but the last one was the most strenuous objection.

Patel: Interesting.

powell: “He doesn’t know me. I don’t know him. I don’t believe in his religion. That’s stupid. Why should I do that?” “I’m not negotiating. If you’re going to stay in the house, you have to do this.” He said, “How long do I have to do it?” I say, “A week.” He agrees to do it. I think he stayed two months.

Patel: Wow.

powell: He comes back and he’s a different person. I said, “How was it? What did you and grandpa talk about?” He said, “We spent hours every day talking. I have no idea what we were talking about,” and yet it had completely transformed him. To this day, his screensaver is a picture of him and my father holding hands. I felt like the spirit that when I cannot reach my son, my father could. It’s not through doctrine, it’s something else that we emanate. I feel like I got a head start on that by being part of this incredible family.

Patel: john, I just have to underscore how remarkable this is. You are estranged from your family as an 11-year-old because of your father’s understanding of faith during a set of really the most formative years in an individual’s life, and when your son is feeling lost and at sea, you send him to the man who pushed you away. It’s just an understanding of the world. You come to the world with an understanding of, “I insist on seeing your gifts.” Does the spiritual practice you mentioned earlier, does it cultivate that? Will you talk about that a little bit?

powell: Sure. It’s interesting. I think I minored in philosophy, not because, whatever, it’s just trying to make meaning where some people say we’re symbolic animals, constantly trying to make meaning. One of the roles of religion is to help give meaning and purpose to life. My meaning and purpose had been disrupted. I started on this journey of this, there is a big hole in my life, because I was not just a believer, I was a practitioner. My life was organized around my family and making meaning.

The meaning was largely there. It wasn’t just a rupture with my father and mother and family, it was a rupture with the kind of world meaning that I had to have held me. It was really hard. 11 was hard, my grandmother died at the time. It’s like another profound love in my life. I was hurting, sad. As I got older, I started looking like a lot of people. I tried different peyote. There has to be more than what’s presented to us. There has to be more than what we call the rat race. I ended up going to India, to Thailand, to Japan.

Patel: This was all part of a spiritual quest?

powell: Yes, exactly. In that process, I started looking at different religious and faith practices. Ended up incorporating some into my own life. Part of my practice is that of what we would call meditation. I’ve been doing that now since 1968, ’69. I’m a vegetarian, partially because of my understanding of life and trying to do the least amount of harm. I know we will do harm in life, we exchange life and death as we live, but I try to do the least amount of harm. In these various practices, I’ve met really, really profoundly loving and wise people. I’ve met people who are a little further on the path than I was or I am.

I am 33 years old, I’m in India at a retreat with Goenka who was a Buddhist teacher. We’d get up 4:00, 4:30 in the morning, do some ritual, have one chapati, and then essentially meditate all day. Then every three or four days, we’d have a meeting with the teacher. He’s a big man. You’re eating one chapati a day. Eboo, my mind is just racing, it’s like, “This is a fraud. There’s no way this guy could be this big and eating one chapati a day. He’s sneaking into the kitchen at night, enjoying…”

Patel: Gulab jamuns and jalebis.

powell: [laughs] Right. I go to have my meeting with him and he says, “How are things going?” It’s like, I’m not opening up to this guy. I don’t trust him. He’s a fraud. I said, “Fine.” He says, “Okay.” Then he says, “If I’ve done anything consciously or unconsciously, intentionally or unintentionally to hurt you or offend you, I ask for your forgiveness.”

Patel: Wow.

powell: I just start crying.

Patel: The guru says– Wow.

powell: When I went back to sit, the energy of anger and hurt and distrust, it was just circulating. I felt it. I experienced it. I could see it. It just kept going. By the end of that day, it was gone. It had shifted. It’s not that I don’t get upset or angry or whatever, but it never came back that way. It was a turning point in my life. It’s like a resolve. It’s like whatever I had been looking for, I had essentially, at some level, not that I may have more work to do, but I had found it.

When I left that meditation, the mother of my children were living together, and she could see the difference. She’s like, “What happened to you? I don’t know if–” She literally said, “I don’t know if I could trust you anymore because you seem to have lost that edge of anger.” What she was saying was that in order to do the work in the world, dealing with all the things we deal with, you needed to be angry.

You needed to have that righteous indignation, which King talked about. Although most of the indignation is not righteous, most of it is petty. She was right. I had lost it. She was also suggesting that if you don’t have that energy, if you don’t have that flame, what keeps you going? What keeps me going, I think, is caring and love.

Patel: I want to get to this notion of the stories we choose to tell, the way we choose to see the world. One of the things that is just so blatantly obvious from all of your writing, from all of your interviews, is you’re always telling the positive story. For you, the story you tell of Katrina is look at the diversity of Americans who contribute in the Black quarters of New Orleans, all Black people are left to fend for themselves and yet there’s this diversity of Americans who contribute.

At every turn, you are telling the positive story and you are saying, “Of course, we need to find a way to help the people we disagree with belong.” You see at one point Black Lives Matter is another way of saying we belong. The set of people, white people who are concerned about the cultural changes in the nation as it becomes ever so slightly more equal and dramatically more diverse, that concern and anxiety we ought to take seriously because they belong too.

You say this in a way, john, that doesn’t make people mad. In the dozen, 15, 20 public settings we’ve been in together as part of the New Pluralist fellowship and being part of the bridging field, you will say these things and people will receive them as gifts of wisdom rather than as condemnation or reproach. How do you do that?

powell: Well, thank you for sharing that. In a sense, I think people can feel love. Even if you don’t say it, your listeners will know that the wonderful friend and colleague– bell hooks, passed a few months ago, she wrote a book about it’s all about love, and not in the necessarily romantic sense, although that’s love too, but the heart of belonging is being seen. We all want to be seen, and we have capacity sometimes, to acknowledge that we’re seeing someone else. Seeing someone doesn’t mean you agree with them, doesn’t mean you can necessarily like them, but it’s like seeing them.

In the Black community, sometimes when someone says something, someone says, “I feel you,” it’s the same thing, I feel you. When a person is felt, what they’re saying, then it’s like, I can exhale. Think about argument. Literally, people are shouting. It’s like, “Why are you shouting? I’m two feet away from you.” Essentially, in a metaphorical literal sense, at an unconscious level, we’re saying the person is not hearing me so I’m turning up the volume. [laughs]

Patel: Right. Even in your casual asides, even when you’re not trying, you have a set of glasses permanently affixed to your face, which says, “I am going to see you in your best light even when you don’t see it yourself.” I just think that’s the most beautiful thing. I taught for a while at the juvenile jail here in Chicago, and there was a famous teacher named Mr. B who would never ask the kids what they did to get into that jail.

Just didn’t want to know, but people asked him why, because, of course, that’s the first question so many people asked, just pretty interested, “I don’t want to see the worst thing somebody’s done. I want to see them read poems, I want to see them learn how to do algebra, I want to see them engage in play and sports.” He wasn’t being ignorant. He was just seeing with a difference set of eyes.

I think your great gift to us, john, is we see you seeing us and you have this endless supply of glasses that you’re handing around, you’re giving people these glasses and you’re saying, “You see them a little differently now. Those people who grew up in one kind of world when I’m watching that world change. You can see them differently. You can see my dad differently.” I just think that that’s such a gift. Just thank you.

powell: Thank you. Thank you. You reminded me of Bryan Stevenson, and he says, we’re not defined by one event, and we’re certainly not defined by the worst thing that we’ve ever done. We could get that sometime. It’s like that person is X. It’s like we have hopefully this long life and we’ll go through many different things, and a lot of times when we do things that are mean, that are hurtful, it’s because we’re hurting.

Patel: Hurt people, hurt people, right?

powell: Yes.

Patel: Last question. You ask us to do hard things and people do that. You have this beautiful line, you quote your friend and one of the people that I’ve read and been guided by bell hooks, bridges get walked on and sometimes they get stomped on and there’s no world without bridges. You got a bridge and that’s cutting against some of the ethos of our times, which is if you feel unseen, you don’t have to see people. If you feel walked on, you don’t have to lay yourself down. You don’t have to do that kind of work. You are telling us we should do it. You’re doing it in this gentle and yet insistent way. That’s intentional it feels to me. Can you talk about that?

powell: Sure. Bridging is actually essential, not just with our families, but we talk about long bridges and short bridges. The short bridges, our family, our friends that we’ve had a falling out with, it’s relatively easy. Not easy, but relatively easy. Long bridges it’s really hard. I think in some ways where we define the place where we won’t go any further in terms of bridges, we define the boundaries of our growth. I’m not got to bridge beyond here. I’m not got to grow beyond here.

We think that that way it’s like, how many of us would say, “I don’t want to grow beyond here.” We all want to grow. I think that’s in essence spiritual or religious practice is about growth, is about being not away from the world. Even if we have to take a break from the hustle and bustle, it’s about connecting to the world on a profoundly different level. I feel really fortunate that I have just an array of friends, different races, different ethnicities, different religious practice. It’s not always easy, sometimes it’s like, “Really?”

Patel: Diversity is not just the differences you like.

powell: Exactly. Sometimes it’s hard. For example, like I said I’m vegetarian. I have a sign on my refrigerator, “This is smoke free meatless house,” and I’m having family come out in a couple of months. One of the questions my sister asked is like, “Where’s the meat?” [laughs] It’s like bringing on the plane. Part of it, Eboo, was not trying not to be too prescriptive as to how people live their lives, I feel like we have to find that ourselves, but also feel like all life is important.

To me it’s not just, I’m an ethical vegetarian, I’m not a vegetarian for health reasons because I feel all life matters, and the way we live our life we constantly live our lives in such a way that most life does not matter. Black lives don’t matter, but neither animal lives don’t matter. They’re there just for– the earth, doesn’t matter.

I didn’t think of my sister that way. That’s how I live my life. I care about people. I think that’s the big thing is that– I was at a swimming pool or recently in this white woman was really making racist statements at me. I got so pissed. I thought of something clever and mean to say about to her back, but then I also felt her. It’s like I don’t want to hurt her. She’s hurt me.

The first impulse was, “You lashed out at me, okay, I’m going to get back at you.” Instead I just was sad for a little bit, and I’m glad I didn’t lash back at her. Part of it I think is a real sense that we are connected and a real caring. If we’re really connected and we care about each other, then you’re less likely as Julie Betler talks about, you’re less likely to lash out at the other because the other is you.

Patel: There’s a story about Martin Luther King Jr in Chicago 1966 Fair Housing March. This is the time when he gets pelted with rocks and bricks, one of the many times, but he says, this is the time when he gets hit in the head with one, he goes down on one knee, blood from his head, gets up and he keeps marching and he gets to this group of white ethnic kids, 700 marchers, 5,000 protesters against King and his 700 fellow marchers. King escapes a security detail, walks up to this group of white ethnic kids, frothing at the mouth, bricks in hand.

He says, “You are so smart and good looking. Why would you want to act like that?” That’s the quality in you. I am going to insist on seeing you as you could be, your best self. I am going to present that to you as a gift. All right my friend, there’s a Grateful Dead line, “I wish I was a headlight on a northbound train,” and I just feel like that’s what you are. You’re a headlight on a northbound train and I feel illuminated and lifted up and guided by you, and I want to thank you for who you are.

powell: I appreciate it. I know we were running out of time, but very quickly you said and I appreciate a lot of wonderful things about me, I hope some of them are true, but I also know that all those things and most of those things are true about you as well. I don’t know if you have time to just say how did you get there? What’s your journey to being a bridger, to being open, to being this deeply caring person?

Patel: There’s an awful lot of this that comes down to my faith too. My journey is there are some similarities. There wasn’t a rupture. There was just more with my family or the Ismaili Muslim faith I was raised with. It was just kind of a distancing. Then I was an angry activist for a set of years in college and I did and said some things that I laugh about now, but honestly I’m embarrassed about them.

I’m embarrassed about how I treated people and I’m embarrassed about how I put them down and created distance. I knew I was doing it and I knew it didn’t feel good for myself, for them. I knew it wasn’t improving the world, and I did it anyway. At some point somebody told me about Dorothy Day and this faith-based approach to the world and I started going to Catholic worker houses, was just blown away by a different orientation.

That sets me on a spiritual journey in which I wind up after two, three, four years coming back to my Ismaili Muslim faith in a story that has some similarities to yours. I had a mentor who was friends with the Dalai Lama, and as I was first starting this organization, originally called IFYC and now Interfaith America, my mentor Brother Wayne Teasdale set my friend Kevin Coval and I up with a short audience with his Holiness the Dalai Lama, Dharamsala in the summer of 1998. I am trying to be a Buddhist. Of course, if you go to see the Dalai Lama, you got to be a Buddhist.

I’m doing my best to sit in meditation, fold my legs just right. You’ve been to India, you know this, can imagine this. Perhaps you lived it. Every time I would try to remove all thoughts from my head which is what I thought Buddhist meditation was, the Ismaili Muslim mantra that my mother would whisper to me when I was going to bed, “Ya Ali, Ya Muhammad,” would keep coming into my mind, and I would keep trying to remove it because I was trying to be a Buddhist. I would fail, and it just this chanting in my mind and I ignored it.

powell: What does that translate into?

Patel: Prophet Muhammad made the peace of blessings of God be upon him. The prophet of Islam, the one who brings the Quran and Ali is the first Shia Imam and Ismaili is a Shia community. It’s just a mantra of the leading figures in our faith. Sit with the Dalai Lama, we have 12 or 15 minutes. I have my Buddhist prayer beads with me. I’m all excited to tell him about this emerging Buddhist prayer meditation practice I have.

The first thing the Dalai Lama says to me is, “You’re a Muslim.” He’s not really saying it as a question, he’s just making a declaration. I paused and I opened my mouth to say, “Actually I’m trying to be a Buddhist.” Then I thought that’s probably not the right thing to say.

[laughter]

I just nodded my head and he says again, “You’re a Muslim.” That’s the beginning of my journey back to my faith. I grow up with stories of faith figures who build, the Prophet Muhammad builds a city, Medina. He gets hounded out of Mecca and he goes to Medina and he builds houses of worship, and he builds a market where people can buy and sell. He creates the Constitution of Medina which is a loyalty pact amongst the diverse tribes of Medina including religiously diverse tribes.

I grew up with stories of the Aga khan who’s the spiritual leader of my community, building a university and building a museum and building a center for pluralism and building hospitals, and every year there’s a different institution that he’s building. I think just deep in my core I have this sense that, if you’re engaged in social change, you’re building things. That’s what you’re doing. Now by the way, I have not always been a builder, but I think that in my return to the Ismaili expression of Islam, one of the reasons it feels like home for me is because it’s got such a builder ethos.

powell: Interesting.

Patel: Thank you for asking.

powell: Oh, not at all. Thanks for sharing.

Patel: Diversity implies difference. Can you talk about the risk of othering that can happen by people that often mean well, progressives and liberals?

powell: I think it’s a great question, sometimes other people in order to belong, so even with other people, sometimes we’re reaching for belonging. I other a group out there so I could belong to my group here. Then there’s also response, the question that comes up a lot is, “Do I have to bridge with those people?”

The answer is you have to just answer that yourself, but wherever you stop bridging is where you stop growing. King talked about righteous indignation and I love that phrase, and I realized at 33 that my indignation was not righteous, just petty. [laughs] I was dressing it up, dressing up a pig in fancy clothes, but it was still a pig. I think there’s a tendency to other in part in self-defense, in part to protect ourselves, in part to define who we are, but it’s still othering.

How far we can go on that to belonging without othering, I think it’s aspirational like the great faiths Christianity, Islam, who really lives the life of Christ other than Christ, but it’s an aspiration. It actually orients us in a certain way. I think that’s how I see belonging. In that process we will other, hopefully it won’t be categorical, it won’t be cemented in place and we can tell stories like you’ve been doing today that help us bridge, help us see and be different even when we’re hurting.

Patel: I appreciate that. I think that that’s perfect. Thank you.

powell: Thank you.

Patel: I hope you found that as moving as I did. The insight that when we stop bridging we stop growing. The lesson that one can be very hurt by someone even your own father and yet admire that person, learn from them, have a version of the very ideas that hurt you, turn out to shape your life. That’s what I took from this interview with john powell.

His father’s rigid understanding of faith excluded him at a very tender time in his life and yet john does not end up rejecting his father or faith, instead he realizes how powerful a force faith can be and he seeks a type of faith that expands the circle of belonging rather than contracts it. He also sees the way faith underpins so much of what he admired about his father. He doesn’t throw out the good with the bad.

Instead he takes the good and grows it. May this conversation about Deen and Dunya, faith and world, be of service to you. May you expand the circle of belonging. May you build bridges across lines of difference, even disagreement. May you grow goodness in yourself and the world. To read more about this conversation and to find resources and stories about bridge building in our religiously diverse nation, visit our website, interfaithamerica.org.

Intro/outro music provided by Mysterylab Music and composed by Mott Jordan.

Credit music provided by Die Hard Productions.

Want to share feedback, suggest a future guest or ask a question? Email Us.

Podcast Team

Copyright @ 2024 Interfaith America. All Rights Reserved. Interfaith America is 501 (c)(3) non-profit recognized by the IRS. Tax ID Number: 30-0212534