Bodies Out of Place: Considering Race and Religion on Campus

January 13, 2021

In the spring of 2010, I made my first trip ever to the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, TN. I was chaperoning a group of students from my alma mater, Baylor University. For those of you that don’t know. Baylor is a Christian University that founded in the Baptist tradition. While browsing the exhibits Baylor University was unsurprisingly absent from the museum’s collections. However, Waco, TX (the town in which Baylor resides) was present. The city was featured in an exhibit on Jesse Washington entitled Waco’s’ first horror. In May of 1916, Jesse Washington, a disabled Black man was lynched and burned to death for the murder of a white woman. A crowd of 15,000 white residents (which at the time half of the city’s population) participated in the brutal event. And while there was a small group of anti-lynching advocates, including Baylor’s President at the time Samuel Palmer Brooks. It isn’t hard to imagine that some of the onlookers included Baylor students. Prior to the trip I hadn’t heard of Jesse Washington, but Black folks at the local church I attended always warned me to be safe and watch my back. Growing up in Waco Black folks knew the name Jesse Washington, and they knew that neither Waco nor Baylor would ever be a completely safe space for Black folks.

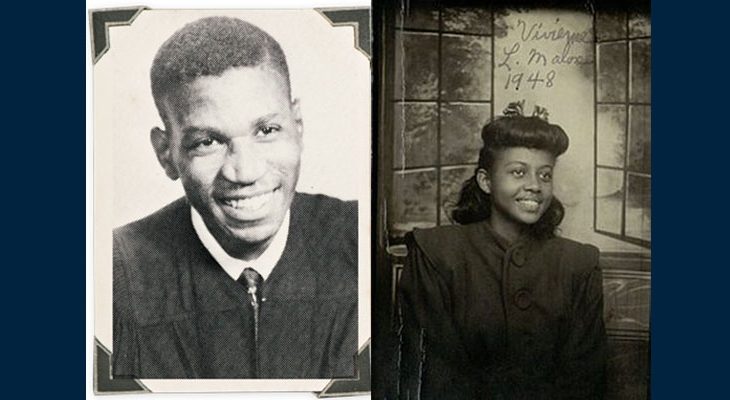

On a predominately White campus that didn’t have its first Black student (Robert Gilbert) or Black faculty member (Vivienne Malone-Mayes) until the 1960s, Black bodies have always be situated as out of place. Walking across campus as a student, I felt my body being marked as an outsider, transient, and disposable. Ironically space where most Black was unable to create a place was the office of religious and spiritual life. Pew data informs us that nearly 3⁄4 of Black people identify as Protestant. At Baylor Black students largely fell in line with national data around religious difference. However, were virtually absent in the office of religious and spiritual life. The Office of Religious and Spiritual Life at Baylor I was one of the handfuls of students that engaged the office. The institution had over a century to build a history and culture deeply mired in White Christian Supremacy. This history lives and breathes with the institution writ large and within the office of spiritual life. I chose to engage the office, but for me to do so required an abdication of any racialized theology. We had to serve a Jesus that reified white excellence and white supremacy. My blackness in those spaces marked me as a target of surveillance. My Black friends never to enter the space. Maybe because it was another site of hyper-surveillance. On-campus it was often impossible for Black folks to just be. Often times lounge areas, kitchen, or activity rooms were sites of surveillance, where it was normal to be followed, tracked, or even outright harassed. Maybe they opted out to avoid another space rife with racial microaggressions.

Obviously, this is not just a phenomenon localized to my alma mater. This marking of on-campus religious and spiritual spaces as places for white students by white Christian supremacy inherently marks Black and Brown bodies as out of place in these offices. This can happen in a myriad of ways but I’ll share two examples using prayer Not only that but particular interfaith interventions can serve to exacerbate the out of placeness. I’ll share two examples both related to interfaith prayer rooms. First, many of these rooms are inherently transient, having rugs and other furniture that are temporarily set up to accommodate the needs of various student religious groups. When students are forced to constantly make and unmake space the development of place becomes difficult if not impossible. Because the room itself communicates finiteness and temporality it is not ever their space it always a shared space. Second, some of these interfaith prayer rooms are not only temporary space but are also subject to increase surveillance and scrutiny. It is no secret that many interfaith prayer spaces that serve the needs of devout Muslim students are notorious sites of surveillance. In order to make these spaces more safe and secure for religious minorities, these spaces are often secured through card readers. Because we know that institutions are not free from government intrusion and surveillance, some campus police in conjunction with local, state, and federal governments have authorized surveillance of the space. This includes the potential use of card readers as a means of surveilling profiling the religiously minoritized. A 2012 report from the CUNY school of law found that NYPD had informants surveilling 7 MSA’s within the city for the radical insurgency. With the creation of these spaces. We must ask the critical questions, whose safety is being considered? And to what end are these spaces being created, curated, and conserved?

Share

Related Articles

Higher Education

American Civic Life

Seven Religion Reporters Share Advice for Reporting in Interfaith America

Higher Education

An Interfaith Dialogue Addresses Race, Equity, and Inclusion on a New Jersey Campus