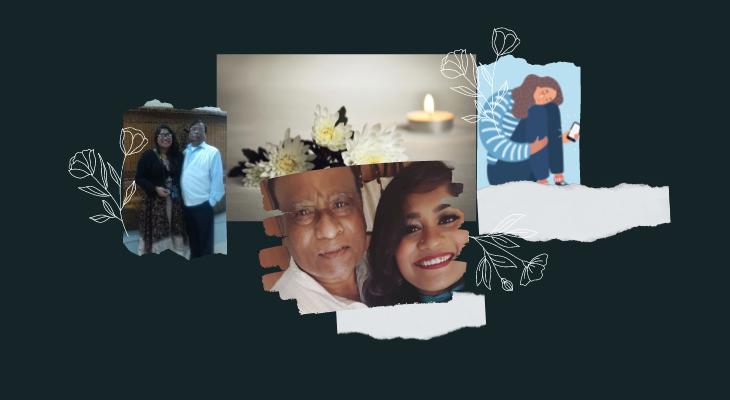

A Year of Grieving: Separated by an Ocean, I Mourned My Father Over the Telephone

December 23, 2021

My father was lying on the ICU bed. His soft brown face was covered in grey stubble, and his skin looked stark against the hospital’s white cotton bedsheets. An oxygen mask lay on the side, IV tubes crisscrossed across his body, and a machine beeped quietly somewhere off the frame. COVID-19 had left a shadow of him behind and watching him lie there so helplessly felt so unreal that it made me want to scream. I wanted to reach through my phone screen and caress his face softly, hold his hand, tell him how much I loved him, how much I wished I didn’t have to see him through a video call. But as always, it was my father who comforted me first – he forced a little smile and asked, “Maa, kissu khaiso?” (“Love, have you eaten something?”)

That was the last thing my father ever said to me. A week later, on March 5th, 2021, he left the world quietly in his sleep as he lay next to my mother, his partner of 39 years, in their home in Dhaka, Bangladesh. He left the world as he had always wanted to – just after the fajr adhan on a Friday morning, considered a holy and sacred day for Muslims. Islamically, it’s required to ritually bathe and drape the body and bury the person as soon as possible – to offer the person dignity and respect in death. Our family and loved ones rushed to my mother and sister’s side to help with the burial and sit with their grief.

Everybody was there, but me.

Thousands of miles away, I wailed in my bedroom in an apartment I shared with three other roommates in a cold and windy Chicago that was slowly waking up from its winter slumber. My friends engulfed me with love, and yet, my grief felt like an ocean like I was drowning and I was so far from the shore nobody could ever reach me here, or save me. My family kept calling me, telling me how everyone came together for the funeral, how they prayed at his grave for his eternal peace. I picked up every single call but couldn’t find the words to speak. Instead, I howled like my world was falling apart, and the miles between us stretched so far it felt like I lived on a different planet. Nothing felt real anymore.

Outside my window the sun set, and the sun rose, and everything that was dead and cold was slowly coming back to life. But inside my apartment, in the midst of life, I could only feel death. I don’t know how many moments, or days or weeks passed – except that each waking moment I missed him, and missed him, and would have done anything to see him again. “I didn’t even get to say goodbye,’” I wailed through my phone – at my sister, my mother, at anybody who would listen. I don’t know if my father could hear me where he is, but I prayed he did, and that he knew how much my heart was breaking without him here.

I am no stranger to long-distance grief. I grew up in a family of Bangladeshi immigrants living in Qatar. For two decades, I witnessed my parents grieve their parents, siblings, friends, over the telephone. I learned, like most immigrants, to fear “the call” — late-night phone calls from home were the flagbearer of unwelcome news. I got used to waking up in the middle of the night to rushed footsteps running towards the telephone, the howling grief, the stunning silence that followed after. I remember how my mother would read the Qur’an, crying softly, the telephone permanently placed next to her when her father died. She would point at the phone and cry, “Everyone’s in there, I want to be there.” When his father died, I recall my father sobbing on his prayer mat, furiously wiping away the tears that wouldn’t stop coming, while his other hand tightly gripped our beige telephone with its wiry cord – he held on to it for dear life while his brother cried on the other end of the line.

Each time, my parents cried like their world had ended. This time, I did too. Our immigrant journey of grieving over the telephone had come full circle.

I know I am not alone in my grief. At that point, we were a year into a pandemic that had stolen over 2 million lives worldwide. For maybe the first time, non-immigrants shared the burden of long-distance grief with immigrants like me, who walked around every day with anticipatory grief – the grief that occurs while one’s facing the eventual death of a loved one. As overwhelmed hospitals discouraged visitors to keep everyone safe, people everywhere were grieving someone, somewhere, over the phone.

A month before my father’s death, I was writing a story about how healthcare workers are trying to find peace during the pandemic. One of the healthcare workers I interviewed told me a story about a daughter who kept calling every day to arrange a Zoom call with her father who was in the ICU battling the virus, and though she lived in the same state, she wasn’t allowed to visit him. The hospital staff was so overwhelmed, no one had the time to arrange a call for her – but when they realized the father wouldn’t make it, they finally called her, and held her up on an iPad as she watched her father through the camera. Later, the healthcare worker told me, “I heard her father say ‘I love you’ but I don’t think she could hear it over the call.’ He passed away soon after.

This sense of collective grief filled me with both despair and hope – to know that we were all on this journey together experiencing a profound sense of loss, and that, maybe, together, we will also find a way to heal.

Amid my grief and the world’s grief, I found myself asking the age-old question: God, why do bad things happen?

I didn’t expect an answer, but in a way, I got one. The one with the answer was Imam Sohaib Nazeer Sultan, Princeton University’s Muslim chaplain and interfaith leader who passed away on April 16 from cancer. Less than a month before his death, he joined his colleague, Vineet Chander, a Hindu chaplain at Princeton University, for a conversation titled “Living and Dying with Grace,” on the philosophies of living life and approaching death from their individual faiths. As fate would have it, I was writing his obituary for work, and came across his wisdom on death:

“We are only temporary custodians and there’s nothing permanent about anything that God has given us … so letting it go means we need to know when the time has come, to say to something that I have tried my best to nurture you, to love you, to develop you, but now, God is calling you to be entrusted in someone else’s hands…it’s most painful, but at some point, we have to do it.”

His words didn’t magically dissipate the giant aching black hole that threatens to rip open my chest every day. But, for the first time in a month, I learned to see my father’s demise in a new light: that as awful it felt, as much as I selfishly wanted my parents to live forever and ever, my father was in pain for so long and he was finally at peace – his time had come.

It wasn’t just me letting go, but my father finally letting go as well. To love and to nourish was the essence of my father’s heart, and it was deeply rooted in his loving submission to God, and he embodied his faith in every action. My father never missed a prayer, even when he was in his last days and often too dazed and confused to remember where he was, he would wake up like clockwork at the right time to offer his prayers. He taught me that faith was personal and that the love you put out in the universe will always make its way back to you.

And he gave the world so much love.

When my sister was born in 1984, my father worked as an engineer in Saudi Arabia. Long before policies around paternity leave became mainstream, he threatened to quit his job if they didn’t give him a month’s parental leave, and when he finally came home, he didn’t leave my mom and sister’s side unless he had to. Even in the blistering humid Dhaka summer, my father cushioned my newborn sister with giant pillows and blankets, afraid that she might roll over and fall when he was not looking. He filled her bottle with formula every hour, afraid that feeding her the old bottle would make her sick. In a society that viewed nurturing as a woman’s role, and made fun of my father for being so “soft,” my father blanketed us with all his love and care to shield us from the cruelties of the world. The world feels much crueler after his death – it’s like the outside world has lost its charm, and I crave the familiarity and safety of my childhood, with him by my side.

But I have witnessed how much love the world has to offer too. I have seen the love my father gave come back to him.

In 2013, my father took early retirement from work due to health issues. On his last day in the country, there were no empty corners left in our home – throughout the day people came in crowds to bid farewell. Colleagues, friends, the grocery store clerk he visited every week, the construction workers he supervised on a project once, taxi drivers he had taken out to lunch, everyone whose lives he had impacted with his love, was there. I remember a man who hugged my father and cried, “I have brought you some oranges. Please eat them, it’s all I have to give you.” My father shared the oranges with everyone in the room.

Even in death, he was surrounded by love.

My phone buzzed for weeks with hundreds of messages from friends and family, people who I hadn’t spoken to for years wrote to me too — “I remember uncle would always remember my favorite food and make sure it was on the table every time I came to visit.” “Your father was the kindest man I knew.” “He always made me feel at home.”

Losing a parent is hard, but losing a loving parent is even harder, and it hurts so much because grief is just an extension of our love – the harder we loved, the harder we grieve. I know I will grieve my father for as long as I love him — forever.

As the year comes to an end, we always celebrate the new year with two cakes – one of them for my father’s birthday. This year, there won’t be a second cake, and around the world, there will be empty chairs at the dinner table, and so many people will be in grief. This has been a year of grieving. In Islam, when someone dies, we say: “Innalillahi wa inna ilaihi ra’jiun — Verily we belong to God and verily to Him do we return.” Whether you believe in God, or a higher power, the universe, or nothing at all – I hope that you find peace and that you learn to let go, and hold on to the stories and memories that will keep your loved one’s legacy alive.

Share

Related Articles

American Civic Life

We Commemorate, We Commit: Out of Catastrophe, a Conversation on Connection and Repair

Racial Equity

A Year After George Floyd’s Murder: How Black Interfaith Can Give Hope to America

Racial Equity

It’s the Year of the Dragon in the Chinese Zodiac − Associated with Good Fortune, Wisdom and Success